Posted on April 12, 2010

South Africa is currently debating what to digitise and how to manage digitisation across the nation in various archives, while taking into account our staffing and funding constraints. The Department of Arts and Culture is developing a digitisation policy this year (2010). The Department of Science and Technology is undertaking an investigation of digitisation initiatives across various South African archives, in collaboration with the Carnegie Foundation.

In our debate about camera use in archives during 2009, the Archival Platform found there was considerable discussion about the use of volunteers in digitisation efforts. We even had an offer from one frustrated archives user to donate money for the digitisation of state archives.

We would like to see some discussion about the role of researchers and the public in general in the digitisation process.

Balancing costs and benefits

A recent EU study pointed to the value of social computing in improving government services, government transparency and public engagement with government. The use of volunteers potentially helps to involve the public in the process of archiving, helping them to appreciate the value of archives, at the same time that it enhances access to collections.

Volunteers can never replace expert archival digitisation, inventorying, metadata entry and so on within archives, but the reality is that archive infrastructures are not coping with the volume of work, even in wealthy countries. There is perhaps for this reason an increasing emphasis on the use of volunteers by relatively well-funded archives in the western world, following on the revolutionary success of projects like Wikipedia.

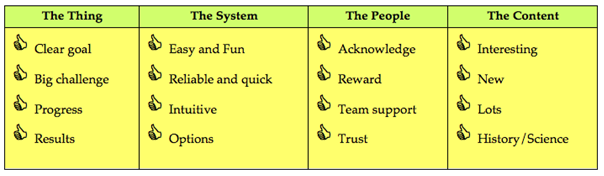

These projects need to be well organised and coordinated, with checks and balances to protect data integrity, but too much emphasis can be placed on the dangers of involving the public in the work of the expert archivist. In a recent article, Rose Holley discussed some of the major recent crowdsourcing projects around the world. She identified a number of features of successful projects, noting that careful planning, coordination, and involving and trusting users paid off in the quality and quantity of engagement:

Holley's features of successful projects

So the question arises, 'how can we use internet volunteers in crowdsourcing digitisation in South Africa?'

Inventorying, metadata, and translations

Archives are drowning under the weight of their inventorying and classification processes. Online volunteers can help generate metadata for digital images. Holley's article talks about the volume and extent of online volunteer tagging projects for images and documents. The internet volunteer 'crowdsourcing'Â idea is being used in the creation of digital archives.

A new initiative called the Extraordinaries helps institutions to harness volunteers' spare time. On this website, the Smithsonian Museum is getting volunteers to tag images from its collection. Any institution can add its own 'mission' for internet volunteers to undertake.

Online volunteers /archive clients can also help correct errors in optical character recognition (OCR), improving the quality of digitised resources (e.g. UCL's Bentham Transcription Initiative and the National Library of Australia's Many Hands project).

Stuart's Blog describes another similar example:

The reCAPTCHA project tries to solve the problem of imperfect OCR in digitisation projects by sending words that cannot be read by computers to the web in the form of CAPTCHAs for humans to decipher. The findings are channeled back to the digitization project.

The National Museum of Namibia has already used schoolchildren to help it digitise the paper-based inventory of its own collection. This helped to provide computers to schools but it did not harness the power of the internet volunteer.

The power of a much wider range of online volunteers became very evident in the recent Haiti crisis. For example, Ushahidi is a free and open source project based in Africa that helps anyone to gather distributed data via SMS, email or web and visualize it on a map or timeline. This helped to visualise the problems and potentials for intervention in Haiti. The tool was also used to map xenophobic attacks in South Africa.

Crowdsourcing tagging or Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is not without its challenges, and tagging in particular needs careful consideration, rules and oversight as illustrated by the experience of the German Federal Archives. However, perhaps it's better to have images online that are sometimes poorly tagged (and could be improved by every new user) than not tagged at all. In any case, users have often experienced frustration with tagging and inventories done by inexperienced archivists. How often do well-informed users have the chance to correct them?

Simply networking experienced archive users could help provide better translations of documents, reading unintelligible scripts. Online forums where queries about finding specific data could be posted could help increasingly harried and overwhelmed archivists to provide a better service within the archives. These benefits would not only be available to those consulting archives online - archivists in the local repositories would be able to improve their service to the client.

Augmenting archival collections

Volunteers can augment an existing programme of archival digitisation. For example, researchers' photos of archival collections, and photos relating to archival collections, could be used by archives and added to their databases. The use of volunteer images in this way requires some thought, on questions of organisation and storage, quality, copyright and access.

Researchers in some South African archives are already asked to give archives copies of the photos they take, but these images are not always put in archival digital collections. Using volunteer images optimally within archival systems requires a system for labelling, managing, classifying and processing the images. This may or may not involve public internet-based access to these materials, depending on the archive concerned. However, images that are not for public distribution can also be archivally useful - digitising collections is also about preservation. Quality of image, although often a concern for archives, may not be a concern for every archival user - until high-quality images are available, many users consider anything tagged and digital better than nothing.

Informally, services like flickr already provide a perfect place for volunteer sharing of archival data. This is not suitable as a long-term solution, as both state and private archives have concerns about intellectual property and ownership over their digital resources. Any archive would like to manage its own digital collection, something which drives most decision-making in their digitisation policies.

As a first step, however, SA archives might find that asking for public submissions relating to their collections on something like flickr might elicit some interesting results - and they could choose to remove material that is subject to copyright restrictions. You can find most of the British Museum's public collection recorded on flickr already and the same will soon be true of many SA museums, heritage sites and archives.

Researchers can contribute other forms of data to archives as well. In South Africa and abroad, many researchers have databases of digitised data that could be very useful to other researchers, and could supplement the digitisation process. Unfortunately, researchers are notoriously bad at sharing this data, and much of it is in outdated and incompatible formats. But at present those who do wish to donate databases have no assurance that they will be used and properly archived.

Researchers need to be encouraged to lodge their research data with the archives concerned. If the data are still being used, researchers could leave them as a bequest to the archive at their death. In the long term, funding would be needed to provide the technical and professional historical skills base to manage such data and make it available to the public. But in the short term, it would be helpful to at least have a place to donate such databases, while working towards providing access to some of the data online.

Crowdfunding digitisation

Where funding for a good public-interest project is short, or difficult to get without strings attached, SA could explore crowdfunding especially for small archive digitisation projects. Because amounts are small, funds would not necessarily depend on the benevolence of the SA middle class, or expats, but might also come from interested individuals in the international community. This may sound difficult to achieve but there are already successful examples of crowdfunding for small archiving projects.

One example of crowdfunding is Polyvinyl, a record company in the US, who recently raised enough money ($18,000) to save 10,000 records from destruction. 'Their distributor's warehouse recently got severely downsized and threatened to destroy 10,000 records due to high storage costs. Beyond the absurd wastefulness, Polyvinyl simply wouldn't part with this incredible heritage. So they asked people to chip in to have the records shipped to their office and clear out some space to store them. In return, backers would get various tiers of CD & DVD goodies from the label's roster, depending on the donation amount. Polyvinyl loyalists met the $1,000 goal mere hours after the project was posted [on a crowdfunding website called kickstarter]. With 42 days still to go, the effort is already 233% funded.'

Photocopying archives for researchers is a dead end because it provides no digitised copy for use elsewhere; also it exposes documents to unnecessary light, and it often damages them, even when done by library staff. Some archives, including the Amsterdam City Archives and the National Archives of Australia, charge researchers who request a scanned document, and then provide the scanned document to other researchers online (see the ArchivesNext blog on this). This is another way of crowdfunding digitisation, and it is already practiced by some SA archives.

In short...

We need sufficient funds and investment at national level for optimising digitisation processes within South Africa, at both public and independent archives. The focus should be on good planning so that funds are not wasted, and on coordination so that scattered effort is directed to common goals. DAC's work on national digitisation policy and the efforts of the DST on digitisation of archives should be coordinated.

Online volunteers are a largely untapped resource for archives. International experience has shown that volunteers can perform an important role in digitisation projects, and encouraging volunteer involvement helps to improve the transparency of government and to create public investment in the archive.

Most existing crowdsourcing initiatives are based outside Africa, using non-African volunteers. African internet penetration is still the lowest of any continent in the world. Will this work in South Africa, and will it work now?

Any African project to digitise archival collections will be strapped for cash. The idea of using micro-donations to support a national digitisation project is tempting, but realistically it may be more feasible to supplement funding of specific projects in independent archival institutions.

But we shouldn't underestimate the power of the online community in undertaking tagging, transcription and OCR checking, and in augmenting existing digitisation processes. In Africa, and in the African diaspora, we already have many people online who would be willing and able to tag Africa-related images or proof-read digital data in indigenous languages; much of the colonial archive can be accessible to volunteers who have expertise in English, Portuguese and French. In the future, we expect to see African internet penetration rise, and costs decrease.

If we ignore the opportunities presented by crowdsourcing and crowdfunding, South Africa will lose out on an opportunity to digitise its archive more rapidly, and increase public engagement with it. Involving the public in this way, and in others, should be part of our planning right now. Archives around the country could adapt and experiment with various ways of involving archive users and the public as online volunteers in their digitisation processes.

What are we waiting for?

Harriet Deacon, former Director of the Archival Platform is now an independent heritage consultant, and a correspondent for the platform

Blogs of interest on this topic

http://dablog.ulcc.ac.uk/category/services/linnean-online/

http://dablog.ulcc.ac.uk/2009/11/30/dpc-agm-and-thoughts-on-preserving-research-data/

http://www.archivesnext.com/?p=1175

http://blogs.ifla.org/stuart/2009/11/11/crowdsourcing-at-minerva/