Posted on September 16, 2010

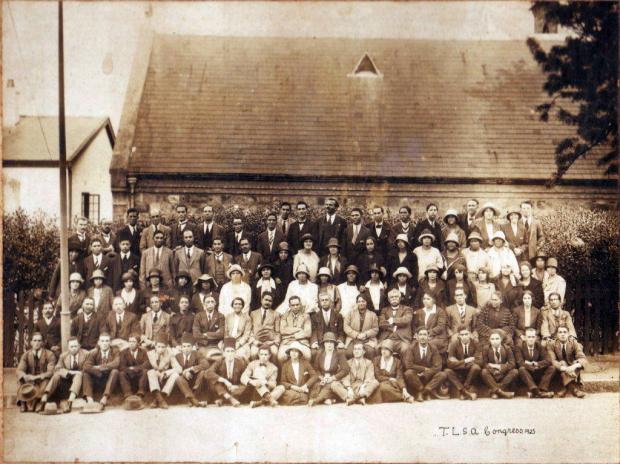

Delegates to the Teachers' League of South Africa (TLSA) conference, 1925. Dr Maurice served as vice-president of the TLSA in the mid-1950s. For him, as with others of his generation with a similar political persuasion, teaching was more than a profession, and was rather a calling. This idea of teaching as a calling is written into the motto of the TLSA - 'Let Us Live for Our Children'. Dr Maurice was also a stalwart of the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM), which had close links with the TLSA. He was among those who addressed the Anti-CAD (Anti-Coloured Affairs Department) Conference in 1943 on the role of the "Non-European' teacher in the liberation struggle. It was the Anti-CAD movement that spawned the NEUM, with its ten-point programme for change. While he was principal, Harold Cressy High was perceived by many as an NEUM school, as was the case with Livingstone, Trafalgar and South Peninsula High Schools.

Recently, an old teacher of mine from my days at Harold Cressy High in District Six, Cape Town, phoned me out of the blue. It was 38 years after I had left school, in which time I had neither seen nor spoken to him. He wanted to know whether I would be interested in working in a team on a school heritage project, an element of which would be a display on Heritage Day this year. My response was to tell him that people of colour, those who carry the history and stigma of being classified as 'coloured', are hardly represented in our museums, that it was heartening to know that more and more communities in South Africa were realising the value and importance of heritage, and that the project was right on the mark.

My old school is named in honour of Mr Harold Cressy (1889-1916), who emerged as a figure of considerable clout in the early 20th century, and at a time when modern intellectuals of colour were beginning to make their mark as leaders of the oppressed and significant forces for change in South Africa. He was the first person of colour to obtain a BA degree, the first president of the Teachers' League of South Africa (TLSA) when it was established in 1913, a principal at Trafalgar High School in District Six, and a key figure in the African People's Organisation (APO) in its early days at the turn of the 20th century. Both the TLSA and APO are critically important organisations connected with the education and political struggles of disenfranchised people at the Cape.

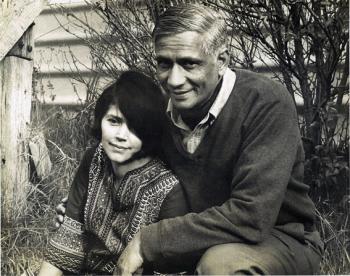

My father, Dr Edgar Maurice (1919-1994), became principal of Harold Cressy High in 1952. He was very much a man in the mould of Harold Cressy. Like him, his outlook on the world, and political and educational vision, was shaped by the politics of racial exclusion after the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910. Moreover, like Mr Cressy, his quest was for all people of colour to be accepted as equal in a society that cast them as inferior on racial grounds. Both of them were dedicated to the idea of upliftment through education and both believed that people should be judged on their merits. Both saw education as the way to counter racial prejudice and as a means to social acceptance in a society that regarded people of colour as inferior; and both were activists, as much as educators. They believed, and lived by, the idea that it was through education and the cultivation of knowledge that one could prove oneself to be equal to anybody and stand tall in the world.

Besides a photograph in the District Six Museum in Cape Town, Edgar Maurice's place in public history is scant. His story, and the values and ideals for which he and other teachers stood, remains to be told in broader public life and beyond the Cressy milieu. So, when my former biology teacher, Lionel Adriaan, phoned me about the Cressy heritage project, my thoughts turned immediately to my father.

Some years ago, in 1999, I curated an exhibition for the SA National Gallery entitled "Lives of Colour: The Cape Photo Album'. My aim was tell a story about the life experiences of so-called 'coloured' people. Every picture tells a story, it is said, and my approach was to construct the exhibition around photographs in the albums of various families, so creating a particular edition of people's history. Photos are triggers to memory and what I did was to record and interpret the stories told by those participating in the project as they responded to certain photos in their albums. What I ended up with was a set of written stories with photographs telling about oppressed life under colonialism and apartheid in its various facets, ranging from camping to school days, from forced removals to sporting life and from partying to rearing children. What resulted from this project was an exhibition in a national museum that spotlighted ordinary, everyday people, and a narrative that contributed to an unfolding story about our collective history and identity.

My approach to representing Edgar Maurice for the Cressy heritage project was something akin to the strategy adopted for 'Lives of Colour': I wanted to construct a picture of his life and times based on selections from the family archive. Of course, because he had already passed away, I didn't have the benefit of discussing either the photographs in the Maurice family album with him, or the content of the reams of paper he left behind containing his thoughts and ideas. But, as my aim was to make meaning of his life, I spoke to various people who knew him, among them his wife, old colleagues of his, and other members of the Maurice family. Sometimes these discussions were about the meanings locked in the family photographs and other memorabilia. The people I talked to related their accounts of him, passed on new information and verified certain factual details, dates mainly. Much of what they said confirmed what I already knew, although the dialogues with those who knew him also revealed features of his life unknown to me.

Once I had accumulated enough research information, I put it all together - the visual evidence of his life drawn from the family archive, an overarching text on his life and times, and my own understanding of 20th century history at the Cape and of South Africa, all of which was filtered through my own biases, conceptions and political understanding. Some might agree with my representation and interpretation of Edgar Maurice's life in the way I've cast him, others not. But that's in the nature of reconstructing history: biographical and other accounts are inevitably subjective and ideologically slanted. From this there is no escape.

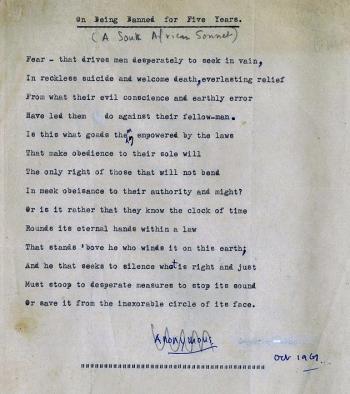

My father was a person of great integrity. He stood for excellence in any task undertaken and second best was never good enough. You always had to put your best foot forward. So having assembled my account of him, I approached a professional designer to assemble a large format display board as a dedication and tribute to a man who relentlessly strived to cultivate the potential of young people, and who gave most of his life to preparing them for a life in a society where they were severely disadvantaged by political iniquity. His life-work was to liberate minds, helping them to realise their humanity. Today he is not quite a forgotten figure, but certainly buried beneath the selections that democracy has made for profiling in public spaces - the Mandelas, Bikos, Sisulus and so on. My effort to represent my father in a public space is therefore a challenge to democracy itself to open its doors more widely. There's a bigger story to be told.

Emile Maurice is an independent heritage practitioner