Slipstitch: candid scenes from within seamstresses’ archives

curated by Roxanne Jones

Slipstitch: candid scenes from within seamstresses' archives is a digitally contextualized exhibition inside my mother’s sewing-room, visually rendered through a 360-degree camera. Whilst the exhibition is engaging with my original research object - my mother's straight-stitch Afsew sewing machine - its context within a home industry fosters an honouring of the working seamstress and homemaker's multiple forms of labour.

Further to my research project's primary focus which is on the clothing and textile manufacturing industry in Cape Town, there are strong contrasts which develop between the factory workspace and the home workspace - and these are curated within the exhibition. The similarities between each of these spaces are highlighted in the sharing of some of these stories, but also the silent resilience of these seamstresses. Aspects of running a home industry or ‘workshop’ - the hours of labour, notions of privacy, and pride in one’s work – are interlaced throughout the many layers of the exhibition.

The home industry, ‘Slipstitch Interiors’, that my mother made and self-managed from 1989 to 2006/2007 is used as an example of how the craft is used out of domestic and financial need to ‘make’ a home and to rear children. The domesticity of this craft within the realm of interior decorating or 'soft furnishings' is rendered through various audio-visual elements presented through seven different 360-dimensional scenes of the sewing-room. Each scene carries snippets of the voices of four different constituents who have interacted with the larger textile industry which, when digitally ‘placed’ in the room, hold uncanny connections with the objects, and elevate voices which have been marginalized in archival documents.A living archive is thus constructed through deconstructed oral interviews, which speaks to the lack of information on both the interpersonal relations and powers at play in this industry and the lineages of craft in the lives of black and mixed-race female workers. This exhibition is an attempt at digitally rendering the marginalized stories of seamstresses with those of the interior decorator, and the factory owner; it is a juxtaposition of these real lives with the finished designer products and Westernized ideals of comfort and work. The contemporary reality in post-apartheid South Africa and specifically the Western Cape in this exhibition questions what has really changed in the last three decades for 'coloured' seamstresses in their contribution to the global economy.

Visit Slipstitch: candid scenes from within seamstresses’ archives

Fugitive Libraries

a research essay and curation by Sibulele Mabe

South African students are trained and orientated to think within a particular silo, where they are obliged by Euro-American theories to think in a particular way. Most Africans read the canon through the eyes of Euro-American culture and the Eurocentric framework of scholarship. This has led young Africans, such as myself, to unconsciously learn to see ourselves in foreign norms and images, and to ‘‘regard our specific African experiences as insignificant elements for academic scholarship’’ (Mkhize & Nwoye, 2017). So, it became important to find ways to challenge this theoretical apparatus thrust upon us.

The version of historiography institutionalised in South Africa ensures that students are unable to engage with their languages, struggles, and histories in the curriculum that they are asked to learn from.

There is a long list of brilliant African scholars whose contributions are not visibly studied, whose work is unpublished, or who themselves were marginalised for being black and denied the opportunity to form part of knowledge-making. It is precisely because of this invisibility that there are knowledge gaps and silences in South Africa’s scholarship. My curatorial gesture attempts to map out the ways in which we can begin to break this homogeneity to reflect on a more equitable, just, and inclusive space in the canon. The gesture came from the need to see writings of South Africans who have been forgotten over time re-emerge from the dusty shelves of history in order to address the deficit of historical scholarship in South Africa.

Essentially, it acts as an aid to contemporary scholars who seek to interrogate South Africa’s historiography.

The reading list deliberately promotes writing by and about black South Africans, as many of their books are hard to find, especially those written in indigenous languages.

Ultimately, this project came from the need to interrogate Western discourses on Africa and how the library has structured knowledge about Africa. So that we might imagine alternative futures where we can begin to build cultural heritage systems that transcend colonial pasts.

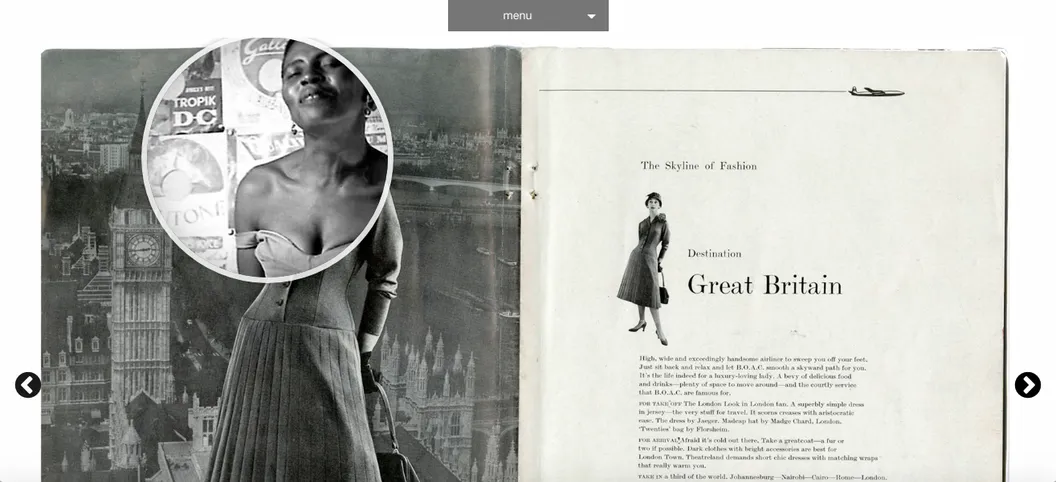

Redressing Vogue

curated by Jade Nair

Redressing Vogue seeks to uncover and expose the sexist and racist ideologies and practices that informed the making of a 1955 Vogue South Africa and Rhodesia supplement. On the surface it is an innocent representation of glamour, however, the world it depicts is populated solely by white people, a manifestation of apartheid’s ideological goals – that leisure and luxury be reserved for them. In its failure to reflect a larger and more diverse South African context, it denies both the existence of black bodies and their participation in, and contributions to, fashion. This exhibition creates connections between the content, and gaps, of the 1955 Vogue and fragments of South African history and the South African present. In so doing, it inserts the stories and bodies of the many silenced and ignored by ‘white’ spaces such as Vogue. Whilst this 1955 Vogue supplement was entering circulation in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Salisbury (now Harare), the community of Sophiatown was being forcibly removed to Meadowlands, the first of many communities to experience the horrors of the Group Areas Act.

As part of a generation that has encountered this history through inherited memory, storytelling and an ongoing societal debris, I have engaged both the form and strategy of collage with the aim of addressing the fragmentary nature of identities and histories that, often, fail to tell the nuanced and complicated stories of the marginalized. The redressed Vogue, presented here, is now filled with fragments of popular culture, political history and contemporary art and fashion. Ultimately, by considering the erasure of black bodies in this magazine and the erasure of black bodies through forced removals, the brutality of the latter becomes evident and visible in the former.

Visit Redressing Vogue

One of Us

curated by Kay-Leigh Fisher

One of Us is an online exhibition and archive. It is based on the study of a cosmetic compact mirror in relation to conversations with collaborators that are reflected in zines. Zines are small self-published magazines, also known as fanzines. In One of Us, zines are re-articulated as a form of alternative exhibition which conversationally explores the duality of visibility and self-awareness. As an alternative space, zines provide anyone who practices within its pages a safer stage on which to perform their identities by offering an unregulated exhibition space. One of Us negotiates insider and outsider identities from an individual perspective. The zines in the archive are based on a series of conversations with two young transgender women in South Africa reflecting on our experiences of performing race, sex, and gender norms like they are rituals and our only ways of being. As individuals we painstakingly control how we appear to others and in turn make aesthetic judgements based on how they appear to us. The intricate concept of Realness is something that we negotiate generationally and socially. These essentialist constructs attempt to neatly categorise everything in our society while isolating outliers that have been perceived as ‘wrong’, instead of opening up dialogues. Youth subcultures consciously use tools like mirrors, zines and screens to mobilise their ability to blow up compact idealisations with their blissful disidentifications. Their identities and representations reframe how people are seen and allows us to consciously reimagine the world. One of Us invites you to suspend your idea of what ‘normal’ and ‘real’ is for a moment by honestly considering the biases of your position through introspection and self-articulation.

Visit One of Us

Alternative Exhibition Spaces

curated by Thabang Kanyane

Since the inception of the Royal Academy of Painting and of Sculpture (1648) in France and its Salon (1667) exhibitions to the contemporary moment, artists and curators have experimented with exhibition spaces which are alternatives to the traditional spaces – those of the Salon, white cube commercial galleries and museums. These spaces offer a freedom of experimentation which is rarely afforded to emerging artists and curators. During the 1960’s and 70’s, artists working in alternative exhibition spaces were intensively experimenting with the art object and challenging its pre-existing notions as a pristine and static object of commodity.

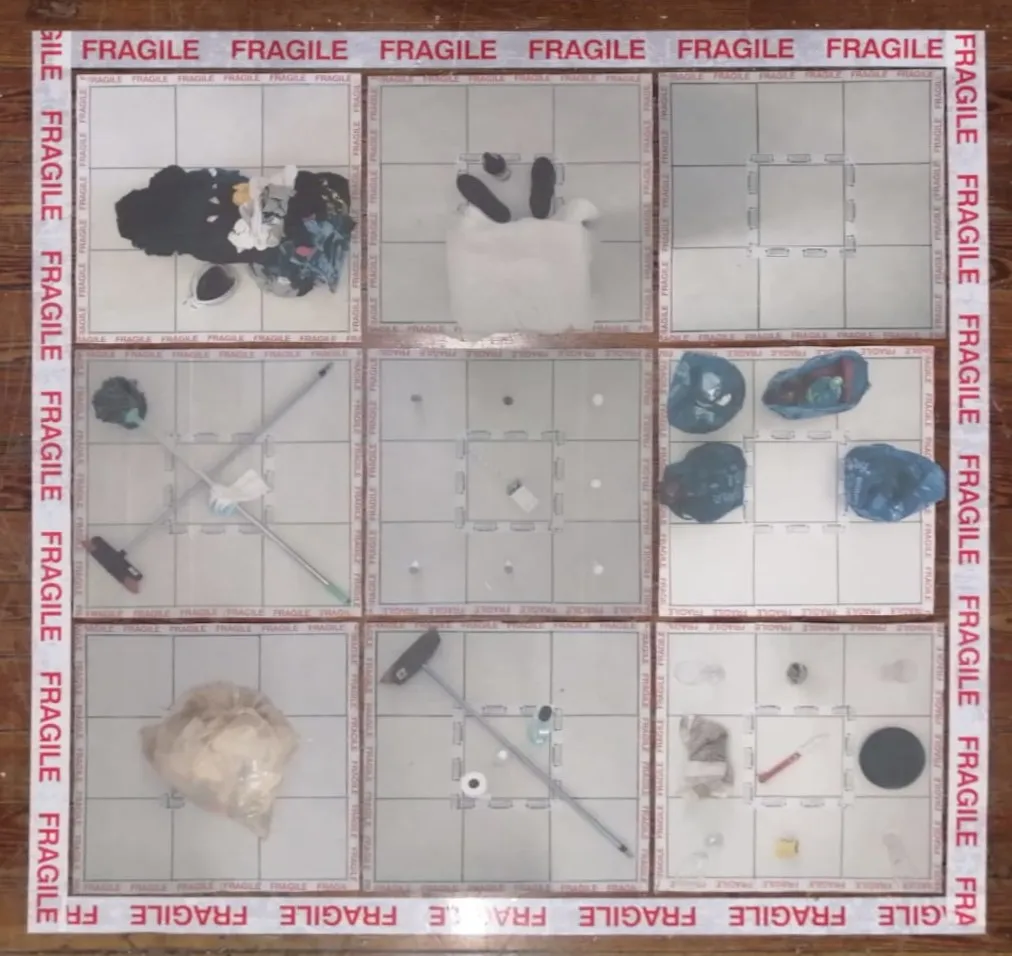

During the period of 7 August – 25 October 2020, artist-curator Thabang Kanyane experimented with the exhibition space as an object and site with the capacity to transform objects and viewer perceptions. In a Muizenberg, Cape Town apartment which is his former residence, Thabang transformed a space consisting of 9 ceramic tiles measuring a total size of 1, 058 x 1, 058 meters into a temporary exhibition space. The exhibitions lasted 48 hours and featured objects which were brought into the apartment for domestic utilitarian purposes or were already in existence within the residence space. The exhibition space was a primary object which transformed the secondary objects which were placed inside the exhibition space. The only trace of the exhibitions is the newsprint photographs on display, as the secondary objects were distributed back into the cycle of the household after the momentary shift in their status within the exhibition space.

Across the month of November 2020, with the use of two distinct tapes, Thabang moved across the Cape Town suburbs of Rosebank and Mowbray claiming Alternative Exhibition Spaces. The size of the taped spaces measured 35 x 35 cm; this is the total size of one ceramic tile in the former exhibition space in Muizenberg. The photographs from these interventions were curated into two zines.

Denim Care

curated by Lucie Panis-Jones

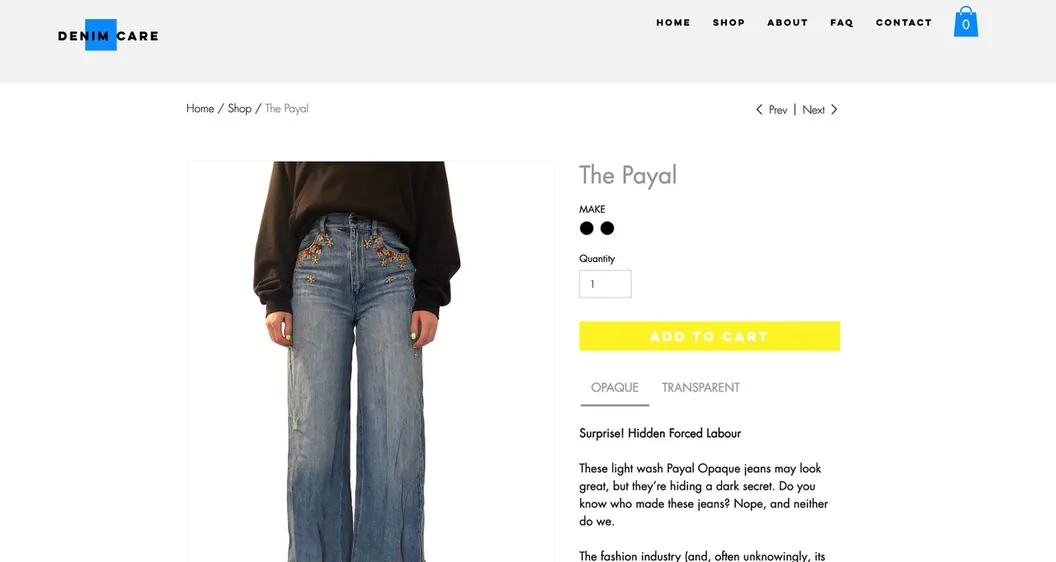

Denim Care aims to open up new perspectives on our clothing and instil a newfound curiosity and appreciation for textile work and for the invisible labour that goes into making the clothes we wear.

The exhibition is a virtual shopping experience for the viewer, subverting the commonly seen capitalist online shopping model. On the site, the viewer is led to believe that they are simply shopping for a new pair of jeans. In the process, however, some of the complex notions tied to the raw materials, manufacturing process, the garment’s use and end of life cycle and impact are slowly revealed in playful, engaging, lighthearted ways. With this format, Denim Care is able to engage and inform the audience without alienating or overwhelming them. We just don’t want to hear (or remember) the bad things. Indeed, research shows that people are very good at avoiding unpleasant or difficult information. Why? It seems that there are three reasons: either because it brings about negative emotions and diminishes the pleasant emotions, or it makes them feel obligated to act on it when they would rather not not have to do anything, and finally because the information makes them question their identity or beliefs (Sweeny, K., Melnyk, D., Miller, W., Shepperd, J., 2010).

Taking inspiration from participatory art, the viewer is asked to actively engage with the site, occasionally prompted to take action, both virtually and physically (for instance, in order to access a discount code, the viewer must complete a manual exercise). These tasks help convey the intricate, tedious or demanding work involved in garment production, and invite the shopper to take a moment to reflect on their actions. Viewers are occasionally asked to use objects from their own homes as props, which help establish more personal connections to the work and foster empathy (if not empathy, then at least some form of curiosity) for garment workers’ unrecognised labour.

Visit Denim Care