In this lecture at Hiddingh Hall on the 30th August, 2011, hosted by the APC, Professor Stephen Greenblatt took a rapt audience on a journey across the centuries, as he gave the audience a heady whirlwind tour of his latest book, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, published in 2011. In it he charts the riveting tale of how the last surviving manuscript of an ancient Roman philosophical epic survived the so-called Dark Ages to be uncovered on a library shelf nearly six hundred years ago by a short, genial, cannily alert man who saw with excitement what he had discovered and ordered that it be copied.

That book was On the Nature of Things by Lucretius – a beautiful poem of the most dangerous ideas: that the universe functioned without the aid of gods, that religious fear was damaging to human life, and that matter was made up of very small particles in eternal motion, colliding and swerving in new directions.

Greenblatt was awarded the American National Book Award on 15 November, 2011.

Lucretius’ great poem De rerum natura, lost for more than a thousand years and then recovered in 1417, denied divine providence, celebrated pleasure as the highest good, and declared that the world consisted of atoms and emptiness and nothing else. This lecture is about the long gap between the return of these radical arguments and their assimilation. How do intolerable ideas survive in an intolerant age?

Everything depends on the circumstances in which something comes to light: the networks of communication and interest, the intelligibility and credibility of the discoverer, the timing. For the discovery to count, the ground must be prepared, and on occasion prepared not only by awakening interest but also by massive, catastrophic loss. If virtually all the works of the Greek atomists Democritus and Leucippus and most of the works of Epicurus had not vanished, if the Greek and Roman philosophical schools had not all shut down, if the public libraries in the Roman world had not closed their doors as the empire crumbled, if so many ancient books had not been destroyed or dispersed on the winds, if Christianity had not utterly triumphed over its pagan rivals, if pain had not for centuries been exalted above pleasure as the source of the deepest human value, there would have been no shock waves when Lucretius’ De rerum natura returned to circulation in 1417. At the same time, for that return to have occurred at all depended on someone noticing and being interested. That someone was an Italian bureaucrat named Poggio Bracciolini.

Poggio was an unusual, gifted, even fascinating man, but he was not a giant – a Galileo, a Newton, or an Einstein. He was the agent through whom something important happened. That is, he was a “carrier.” There is no evidence that he himself fully grasped the importance of what he had brought to the surface, nor did any of his immediate contemporaries seem to do so. We cannot be certain, of course, since it would have been extremely risky to plunge too deeply or enthusiastically into the content of Lucretius’ poem, a poem that denied divine providence, celebrated pleasure as the highest good, and declared that the world consisted of atoms and emptiness and nothing else. This lecture is about the long gap between the return of these radical arguments and their assimilation. How do intolerable ideas survive in an intolerant age?

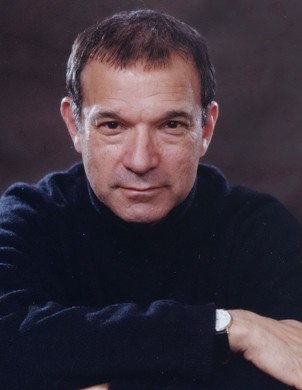

Stephen Greenblatt is Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. He is the author and editor of numerous books, including The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (2011), Shakespeare’s Freedom (2010), Will in the World (2004), Hamlet in Purgatory (2001), The Norton Anthology of English Literature (general editor), The Norton Shakespeare (general editor), Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World (1991), Learning to Curse (1990), Shakespearean Negotiations (1988), and Renaissance Self-Fashioning (1980), among others. He is the co-author (with Charles Mee) of a play, Cardenio, and is the founding editor of the journal Representations. Among his many honors are the Mellon Distinguished Humanist Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Wilbur Cross Medal, and memberships in The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Greenblatt was awarded the American National Book Award on 15 November, 2011.