FOREWORD

by Marilyn Martin

Malcolm Payne’s installation, Face value: old heads in modern masks, a visual, archaeological and historical reading of the Lydenburg Heads, impacts dramatically on the national art museum, highlighting – in a manner different from any of the exhibitions organized hitherto – aspects of changing parameters and value systems. This exhibition proclaims a territory where shifting definitions of art, the meaning of objects, the contexts of spaces as well as the politics of culture can be examined.

But before entering into any discussion of the radically different context in which the Lydenburg Heads are placed, it is necessary to be reminded of Susan Vogel`s statement that (with the exception of some Western art created since the late eighteenth century), “Almost nothing displayed in museums was made to be seen in them” (Karp & Lavine 1990: 191).

When objects enter collections, original context is erased as there is no single authoritative way in which to display them. There are no proven methodologies and each museum environment can only tell part of the story, produce part of the context. Each exhibition is open to multiple perspectives and interpretations, both in terms of the aspirations of curators and responses from viewers – each is contestable.

When Neville Dubow introduced Pippa Skotnes’ exhibition and the launch of her book Sound from the thinking strings at the South African Museum in May 1991, he asked questions about the cultural repositories which lie on either side of Government Avenue, about the common denominator between art and science and what the two institutions have in common. He spoke of objects in the S A Museum which could easily find a place in the art museum across the way. He fantasized about digging a tunnel which would join the two buildings and what one would display in the underground concourse directly under the avenue. He linked these ideas to Sound from the thinking strings. As a member of the audience I also thought that the event could have been equally appropriate at the SANG (South African National Gallery) , although the presentation would have been entirely different. Some months later, in discussion with Malcolm Payne regarding his own project, Face value, I expressed our enthusiasm and offered to host this exhibition and launch of his book.

“There is no exhibition without construction and therefore – in an extended sense – appropriation.” cautions Michael Baxandall (Karp & Lavine 1990:34). Having displaced objects and stripped them of their specialness and original meaning, museums have to compensate by the act of recontextualization. Ivan Karp describes the context offered by a natural history museum as follows:

Natural-history exhibits display objects that are not produced by human agents who have goals and intentions. The theory of evolution is used in natural-history exhibitions to explain how species evolve. These exhibitions do not examine the intentions of plants and animals. Problems arise when objects made by humans are exhibited in natural-history museums and the exhibitors believe that theories of nature can substitute for accounts of cultural factors such as beliefs, values, and intentions (Karp & Lavine 1990: 23).

In negotiating the loan of the Lydenburg Heads from the S A Museum, there was a condition that associated pottery and other artefacts from the site would be included in the exhibition; staff of the institution felt that it was important to provide viewers with the contextual material. This created an interesting situation and the dynamics and complexities peculiar to the SANG were once again thrown into relief, demanding discussion and evaluation.

Since October 1991 items of beadwork and blankets have been incorporated into exhibitions – displayed for their formal qualities and for their affinities with other works in the same room. We have been going to some lengths to provide information and documentation that elucidate works on display; we have been seriously taking into account and mediating the divide between social meaning and aesthetic contemplation. At the time of Face value: old heads in modern masks, there were two other exhibitions at the SANG that deal with southern African art. Transformed fibres, an exhibition of objects selected from the Standard Bank Foundation Collection of African Art, curated by Nessa Leibhammer, contains texts and photographs which are designed to supply some of the missing contexts for the many different objects created largely from hand processed plant fibre. Ezakwantu: beadwork from the eastern Cape, curated by Emma Bedford and Carol Kaufmann for the SANG, placed the spotlight both on the formal beauty of the pieces and on their historical, social, cultural and political significance. A multi-disciplinary approach informed the exhibition and the catalogue, including archaeology, history, art history, anthropology and specialist knowledge gained from first-hand experience. Beadworkers, videos and an interactive map, as well as an extensive cultural and educational programme, accompanied the exhibition.

But the Lydenburg Heads are vastly different from beadwork from the eastern Cape, or from the objects shown on Transformed fibres. We do not know anything about them, or about the thoughts and intentions which inspired their makers; there are no voices from the past to tell their story; we can neither know nor understand them. Staff within the SANG had differing attitudes to leaving behind the archaeological past of the Lydenburg Heads, but Malcolm Payne, who had the last word, was adamant that associated fragments would not be included in his installation, and that there would be no explanatory text on the walls. Graham Avery of the Archaeology Department at the S A Museum graciously conceded that the artist/curator’s demands in this context were different. However, we have undertaken to make information available in which it is emphasized that, in addition to the role of the Lydenburg Heads as works of art, their archaeological context -- associated fragments of pots, shell, iron and bone beads and grindstones -- contribute to our knowledge of the early social history of South Africa and provides an insight into the religious and household lives of the first farmers to arrive in the region some 1500 years ago.

Malcolm Payne’s role is crucial and significant. He conceived the installation, created works of art for it and carried it out in the last detail. He functions as producer, exhibitor and interpreter. This is in itself a radical departure, for in a sense he usurped the curatorial authority and control traditionally exercised by the host institution. But this approach fitted in very well with SANG policy, for we are learning that, with many exhibitions, the process is as important as the end result. We are exploring new ways of curating and presenting exhibitions, and we are tempering and altering our authority.

While we do not adopt an unrelenting ‘Universalist’ approach, circumstances have been created at the SANG for attentive, appropriate viewing of the Lydenburg Heads. They are shown unambiguously as works of art, their specialness and potency are enhanced and the display is designed to stimulate and engender inspection and contemplation. For no matter how we argue, theorize, dissect and deconstruct – no matter what information we provide or do not provide – the Lydenburg Heads are surrounded by enigma and mystery. They reveal extraordinary skill as crafted form and, above all, they have the capacity to elicit what Stephen Greenblatt describes as resonance and wonder:

By resonance I mean the power of the displayed object to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which it has emerged and for which it may be taken by a viewer to stand. By wonder I mean the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention (Karp & Lavine 1990: 42).

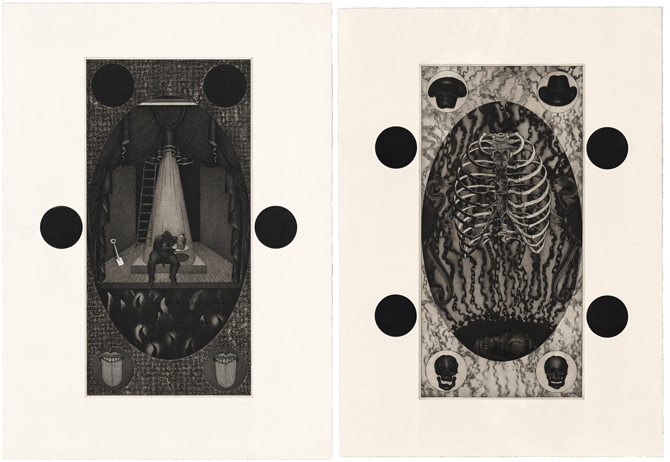

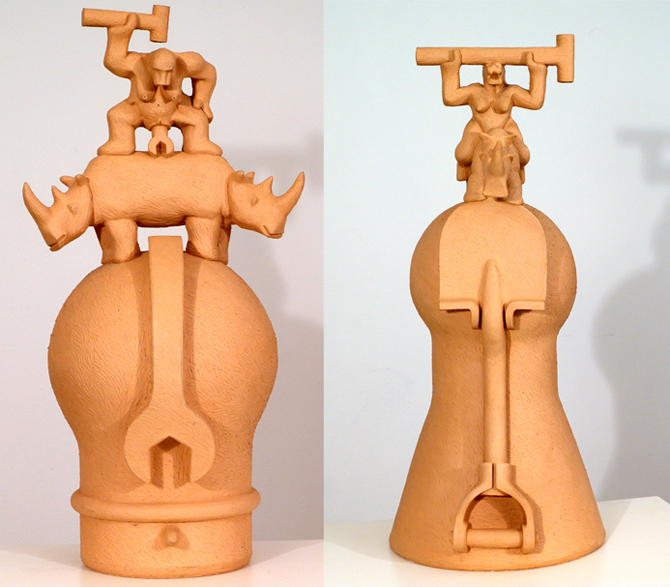

The current sojourn of the sculptures in the SANG is, however, not only a recontextualization into the art museum environment. As part of the exhibition Face value: old heads in modern masks, their mutability is further challenged. Through Malcolm Payne’s intervention, the Lydenburg Heads are presented in the company of his own works, sculptures, etchings, contained drawings and supermarket trolleys. Completely unfamiliar conditions of contrast and comparison are set up, stimulating new and different questions. For example, how does the presence of the supermarket trolleys illuminate their potential link to rituals concerning women or how is the art, craft, sacra debate informed by this juxtaposition with non-art objects? How do these icons of consumerism influence notions about preciousness, possession and proprietorship?

The first public showing of some of the Lydenburg Heads at the SANG in 1971 did not seem to alter or affect their status as art; it did not make them part of the mainstream of the history of South African art. In 1979 the University of Cape Town gave them to the S A Museum on permanent loan.

But from now on the status of these sculptures as timeless, enigmatic and irreplaceable works of art can neither be challenged nor revoked. This raises questions about the history of South African sculpture – as it is currently told – and about the proper home of the Lydenburg Heads. It also draws our attention to the urgency of writing and rewriting the history of art of this country.

Marilyn Martin

Director South African National Gallery

References

Karp, I.,& Lavine, S.D. 1991. Exhibiting Cultures, The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

INTRODUCTION by Malcolm Payne to Face value, old heads in modern masks.

South African cultural histories have, in recent times, become the focus of much critical debate. Indeed, the debate itself may be considered to be a vital form of cultural expression. No exhibition, artist, artwork, political grouping or museum collection is free from its complex scrutiny. The debate aims to restructure representation, rewrite history, to transgress stylistic and cultural boundaries all in the search for dialogue that is meaningful. “History” is its focal centre. It is in this context that this volume will enter the fray, examine the production of meaning and, hopefully, itself become a site of meaning.

The most remarkable issues at play in the prolific global cultural debate today, are not dissimilar to ours. The place of traditional hierarchies has become unseated. We can no longer take our perception of images, the understanding of language, or history for granted. Our cultural practices have been seen for what they are – complex ideological strategies that similarly veil and determine meaning. In the fin de millennium, as we cross the psychological divide into the twenty-first century, culture is being asked to speak in new voice. Protagonists speak of multi-culturalism, some in terms of “cultural nomadism”— a kind of reposited internationalism, or “new universalism” – to gain fresh insights and renewed creative impetus in defence against the pervading bankruptcy of post-modern fragmentation at the core of contemporary art. Faced with this crises of creativity, which is really the recognition of the demise of Western sovereignty, Europe is desperately re-examining its modernist past, its second origin, and it is doing so as a strategy of survival by constructing a reading of the consumption of this legacy by, in particular, Africa. Africa it appears, on the flip side, is doing much the same. Renaming, repositioning, reclaiming and remodelling a past created by the contingencies of geographical and cultural colonialism.

The first making of Africa materialised in a penumbraic half-light along the blurred edges of Europe’s peripheral vision and was brought into focus as the exotic “other”. The obsessional avarice of colonial enterprise fed the retina with objects and materials of desire, which were then quickly melted down, hallmarked by appropriation and set in anthropological and art historical discourse.

Difference was constituted by the supposition that the entire body of world culture from the first light of humanity must be conventionally understood and appreciated in respect of the European visual experience formulated by the Renaissance more than half a century ago. Museum practice and expositions – spectacle contrived to conserve cultural division – of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries exposed exotic as well as erotic object (curios) and people (curiosities) from other cultures. All of this was engulfed by a pre-fabricated imperialist paradigm placing Europe at the centre, mediating the peripheral shade.

The aim of this book is to create a framework for the re-examination of these practices, particularly as it applies itself to categorizing the aesthetic, art/artefact, pluralist and appropriationist products of the debate in South Africa. Seven terracotta hollow modelled heads found near the town of Lydenburg in the Transvaal in the 1950’s, and estimated to be about 1,500 years old, are the stimulus for this book. They are, in many senses, empty – they have no meaning and are opaque to interpretation. We do not know anything about them, nor about the reality they inhabited. What we do know is that they are a part of those South African cultural histories that have been explored by archaeologists, historians and museologists. These sculptures, collectively called the Lydenburg Heads and presently residing in the South African Museum in Cape Town, will act as beacons demarcating the visible field for these arguments.

This book is not about ethnographic declassification, the search for archaeological veracity or an attempt to celebrate the aesthetics of the Lydenburg Heads. If any frame is to be set in place, it would be in the context of coexistent voices harmonizing in inter-disciplinary discourse amplified by the symbolizing capacity of art. A notion of universality in art is firmly rejected. Such notions of authority are totalizing and simply denote a form domination of one set of values over another.

This project steers clear of simple assumptions about transcending cultural boundaries. In fact, it may reinforce them in order to promote a sense of symmetry, ensuring identities are not consumed by a desperately expedient, panic driven, over-arching paradigm of faceless coexistence. The project may examine the past, but it does so in clear recognition that this will always be ideological. The substance of this project perhaps is to constitute some psycho-cultural sense of this time in South Africa.

I invited Martin Hall, an historical archaeologist, and museologist, Patricia Davison to collaborate on this project as I believe their insights into this work are significant. For some time, each has had a working relationship with the Lydenburg Heads, and therefore they share, to some extent, common readings of the complex textuality generated by the heads.

Martin Hall focuses on the Lydenburg Heads as icons and explores “materiality” - the ways in which objects acquire their meanings, a central concern of his discipline archaeology. He begins by discussing the old and much-revered myth of Africa found cloaked by the story of Solomon and Sheba - Judaic, Islamic and pagan.

He asserts that until the mid twentieth century this myth informed most explorations of the African past. The Lydenburg Heads, he suggests, were not susceptible to the same myth. Their discovery occurred after fundamental political and historical shifts had occurred which redefining disciplines of objectivity, and consequently Africa’s past. Embarrassingly, there was no alternative “master narrative” poised to absorb the heads, and therefore they were reduced both to scientific specimens and to vague aesthetic abstractions. His essay is not intended to be an objective history, but rather an argument which proposes that objects, such as the Lydenburg Heads, carry meaning about their origins, and also about the subsequent past and the present acquired by their contexts.

Patricia Davison acknowledges the incompleteness of knowledge. Bearing this in mind, she highlights the acutely fragmented and elusive nature of archaeological knowledge. She traces strands of meaning that the Lydenburg Heads have acquired within their ambiguous status, classified simultaneously art, ceremonial artefact and archaeological specimen. She concludes that there is no definitive affirmation explaining the heads, and therein lies their evocative power as contemporary symbols.

A theme of liminality is explored by both Martin Hall and Patricia Davison in their essays. Similarly, we in South Africa occupy a liminal position in relationship to our past, present and future as we move with hope towards equilibrium. The muteness of the Lydenburg Heads symbolise for me the complex enigma of this passage.

My initial research for this project found form in numerous two dimensional conceptualisations in various drawing media. Some of these images were tentatively assigned to the etching plate towards the end of 1988 when two small editions included iconographic reference to the Lydenburg Heads and a later group of my own sculptures, the Mafikeng Heads. It always had been my intention to extend the range of expression prompted by this research and in particular, within some form of publication. In 1989 I cofounded the Axeage Private Press with Pippa Skotnes. The Press is responsible for publishing fine original hand-made books and prints. The books embody a union of the artistic, the scientific and the literary.

Besides my own contribution of visual interpretations, in the form of etchings, I provide a discussion of my approach to visual art that engages in this kind of plurality. My visual and written deliberations emphasise the parallel reality evoked when conjuring the means to experience the past in the present, catalysed or enabled by the form of the visual as found in works of art. The practice of inscribing relics with value, or consecrating memory in history, formulated in faith, will function as a metaphorical bridge forming an ideological cortex able to link various practices of enshrinement, whether in language, art, religion, the art gallery, museum or iconoclast’s tool-box.

An important sub-text in the form of a question may emerge within the ambit of this production. Where do the Lydenburg Heads belong? It may be argued that their current sitting in the South African Museum, keeping company with fossilised remains of extinct animals, stuffed birds, fragments of meteorites, verist sculptures and whale bones is entirely unacceptable. It may be equally argued that this question is a simple reiteration of the conventional debate which attempts to locate “material culture” in institutions of art, singling out and privileging the architectonic canon of the art museum as a site of valorization, over the context of the ethnographic museum. My position asserts that meaning is contingent, which supports the notion that the hierarchical grading of objects or material culture should be provisionally suspended. In either case, the concept of a value-free territory is problematized. As the essayists have noted, the Lydenburg Heads occupy a liminal space -- below the threshold of consciousness. Perhaps the value of any meditation on displacement demands risk taking -- giving over to an intuitive probing of regions where stimuli are perceived not to be. Regions, where other forms of perception may be evolved to sense the traces of messages lost to memory: perhaps the refuge from the present where at this moment we wander beaconless with no permanence in sight.

Malcolm Payne

Cape Town August 1995

This introduction was reprinted from Payne, M. (ed.) 1993 Face value old heads in modern masks. A visual archaeological and historical reading of the Lydenburg Heads. Cape Town: Axeage Private Press.