Post-Preservation - 28 May 2021

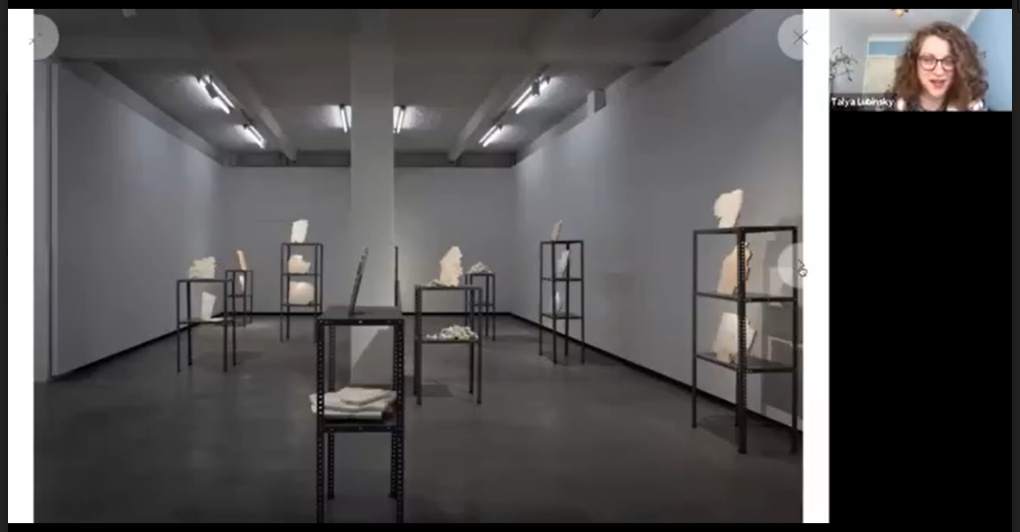

In this session we considered alternate ontologies of matter, materiality and vitality and explored the sometimes unsettling implications thereof for notions of archive, life and commemorations. Talya Lubinsky, a South African artist currently based in Berlin, discusses her exhibition, Marble Dust (2020), as a way of considering the politics and poetics of disintegration and decay in reconfiguring our approaches to heritage management - see her written version here. The exhibition focuses on a particular cemetery archive in Mamelodi, South Africa, as a node for investigating what is at stake when the ostensible durability of stone memorials is placed in tension with the ephemerality of disintegrating paper, and indeed, disintegrating bones. Processes of decay and disintegration are framed not as loss, but as productive material transformation. In her presentation, titled, “Permanence, Decay and the politics of Postpreservation,” thinking through the limits and potentials of what Caitlin De Silvey calls ‘post-preservation’ (Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving, 2017), Lubinsky explores the ontologies of the material qualities of commemorative forms and in so doing, complicates relationships between living and dead, nature and culture, absence and presence.

Further reading:

Fullard, M. (2018). Some Trace Remains. Kronos, 44. 163-180.

Lubinsky, T., Williams, H., & Giles, M. (eds.). (2018). Archaeologists and the Dead. Kronos, 44. 258-262.

Stoler, A.L. (ed.). (2008). Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Cultural Anthroplogy, 23(2). 191-219.

Rassool, C. (2013). Human Remains, the Disciplines of the Dead, and the South African Memorial Complex. In Peterson, D.R., Gavua, K., & Rassool, C. (Eds). The Politics of Heritage in Africa: Economies, Histories and Infrastructures. Cambridge University Press.

Rothburg, M. (2009). Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Témoigner. Entre histoire et mémoire, 119.

O’Donoghue, D. & Conley, B. (org.). (Academic year 2020-2021). In Their Presence: Debates on the dignity, display, and ownership of human remains. [Panel series]. Tufts University, Denver, United States.

Speaker Bio: Talya Lubinsky is an Independent Artist from Johannesburg currently based in Berlin. In 2019-2020 she was awarded a one year residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, funded by the KfW Stiftung. Solo exhibitions include Marble Dust, Künstlerhaus Bethanien (catalogue available here), Berlin (2020), Floating Bodies, Iwalewahaus, Bayreuth, (2017) and If we burn, there is ash, Wits Anthropology Museum, Johannesburg (2016). Lubinsky received an MFA with distinction from Wits University, Johannesburg and is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, based at the Centre for Humanities Research. She is a recipient of an Andrew W. Mellon Centre for Humanities Research Flagship Doctoral Fellowship. Her latest exhibition, Melting Stone, is currently on show at Gedenkstatte Flossenburg, and she has contributed to the Goethe Institut’s Zeitgeister website.

Discussant Bio: Dr Duane Jethro is the Junior Research Fellow at the Center for Curating the Archive.

by Azola Krweqe

In January 2020, South African artist currently based in Berlin, Tayla Lubinsky, hosted a solo exhibition called Marble Dust. It is this exhibition that she unpacks during her Spirals session talk titled Permanence, Decay and the Politics of Post-preservation. During the talk, Lubinsky takes us through the journey of how this project came to materialize.

One focus of the exhibition is on a cemetery archive in Mamelodi, a township in Pretoria South Africa. Majority of the residents of this township were classified as black during the Apartheid era and they came to occupy this space because of the group Areas act of 1950 (South African History Online, 2019). Lubinsky came across a pile of deteriorating records of paupers graves at the cemetery. Her interest was sparked by the Missing Persons Task Team which was concerned with exhuming bodies of political prisoners who died during Apartheid. Their bodies were being exhumed for the sake of being returned to their families for burial and for memorial. Her other context of inspiration was a Jewish cemetary in the district of Neukölln, Berlin, that was being dug up and remodelled into a public garden. Lubinsky says that she was struck by observing the piled up gravestones of the deceased and the seeming lack of care taken with these, in a similar fashion to the record books in Mamelodi, and that it prompted her to think about the relations between the two places.

So, in thinking about this work, I borrow from bell hooks (2014:43) who says that when speaking about a group that we do not belong, moreover a group that we have power over, it is important that think about the ethics around our actions. We are to consider if the work will not be used to reinforce or perpetuate domination. It would have been helpful if Lubinsky was more open or spoke more about the reasons for producing this work. It would have helped that the work does not portray her as wanting to tell the stories of the black deceased. It would be more valuable if the reasons for using the Mamelodi case were explicitly indicated, and her positionality was considered throughout the piece. In closing, although I believe that the work that Lubinsky presents to us is essential in cultural production and conservation practices, I remain however, concerned about the artist’s positionality as it relates to the work at hand.

Watch the recording of the discussion between Lubinsky and Jethro here.

Editors note: some of this important and relevant critique was raised, discussed and addressed by the artist during the session. Please follow the video link provided for more information.

Azola Krweqe is an Honours in Curatorship student at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Her research considers the social landscape and how black women's bodies have been hypersexualised and continously objectified. Through her practices, she hopes to develop spaces where people can easily engage and access art.

References

Colvin, C. J. 2015. Who benefits from research? Ethical dilemmas in compensation in anthropology and public health. Ethical Quandaries in Social research. 57-74.

hooks, bell. 1989. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston, MA: South End Press.

South African History Online. 2019. Mamelodi. [Online]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/mamelodi. (11/06/2021).