Colour, Camera, Colonialism - 30 July 2021

Dr Hannouch’s talk was titled, Gustav Fritsch ca. 1900: Three-Color Photography, Nature, & Colonial Science. In her presentation she traced German anthropologist and racial hygienist Gustav Fritsch's (1832-1927) research on color, its complex relationship to colonial sciences, and the notion of Nature ca. 1900. Fritsch has a complex legacy as an anthropologist and racial hygienist, and for his early use of photography as a scientific tool - view Dr Hannouch’s discussion in the online International Symposium of the European Society for the History of Photography here (April 2022). Fritsch has a strong South African connection, having visited in the 1860’s and producing important, but now also controversial portraits of important political figures on Robben Island and indigenous people across South Africa during a period of colonial domination. He was also an intellectual compatriot of W.H.I Bleek, the German philologist, who with Lucy Lloyd conducted contested ethnographic work with |xam informants to produce an archive of |xam language, myths and stories (see the CCA’s Digital Bleek and Lloyd ongoing archival care and research, and Pippa Skotnes’ Claim to the Country, 2007, available online in the CCA Reading Room). The talk, dealing with a later period of Fritsch’s work, explored relationships between histories of science, human anatomy, technology, and concepts of nature, which would be of wide interest to the South African scholarly community.

Further reading:

Bank, A. (2010). Anthropology and Portrait Photography: Gustav Fritsch’s ‘Natives of South Africa’, 1863-1872. Kronos: Journal of Cape History, 33(1). 43-76.

Hannouch, H. (2022). A Chemist, Not a Photographer: Harald Renbjør’s Three-Color Photography Nils Torske in Conversation with Hanin Hannouch. PhotoResearcher, 37. 114-125.

Hannouch, H. (2022). Gustav Fritsch around 1900: Anthropology and Three-Colour Photography in Imperial Germany. PhotoResearcher, 37. 56-73.

Hannouch, H. (ed.). (2022). It’s not just a picture, it’s a magical object. In Gabriel Lippmann’s Colour Photography: Science, Media, Museums. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 289-295

Hayes, P. (2007). Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography. Kronos: Journal of Cape History, 33(1). 139-162.

Speaker Bio: Dr Hanin Hanouch was a postdoctoral researcher at the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin State Museums (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) in cooperation with the Max-Planck, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz. Beside her monograph on colour photography in Imperial Germany focusing on its ties to colonialism, she is the volume editor of Gabriel Lippmann's Colour Photography: Science, Media, Museums with Amsterdam University Press (see “A Critical Introduction” here, July 2022) and the guest editor of the journal PhotoResearcher No. 37, “Three-Colour Photography around 1900: Technologies, Expeditions, Empires,” (April 2022). Dr Hamouch guest-curated the exhibition Slow Colour Photography at Preus Museum, Norway and she is the permanent Curator for Analog and Digital Media at the Weltmuseum, Wien.

Discussant Bio: Dr Duane Jethro is the Junior Research Fellow at the Center for Curating the Archive.

by Sihle Sogaula

In this session of the Spirals Series titled ‘Gustav Fritsch ca. 1900: Three-Color Photography, Nature, & Colonial Science’, Dr Hanin Hannouch explores the practice and work of Gustav Fritsch, a German anthropologist and racial hygienist, revealing the entanglements in his use of three colour photography and colonial science in the name of technical advancement and political victory.

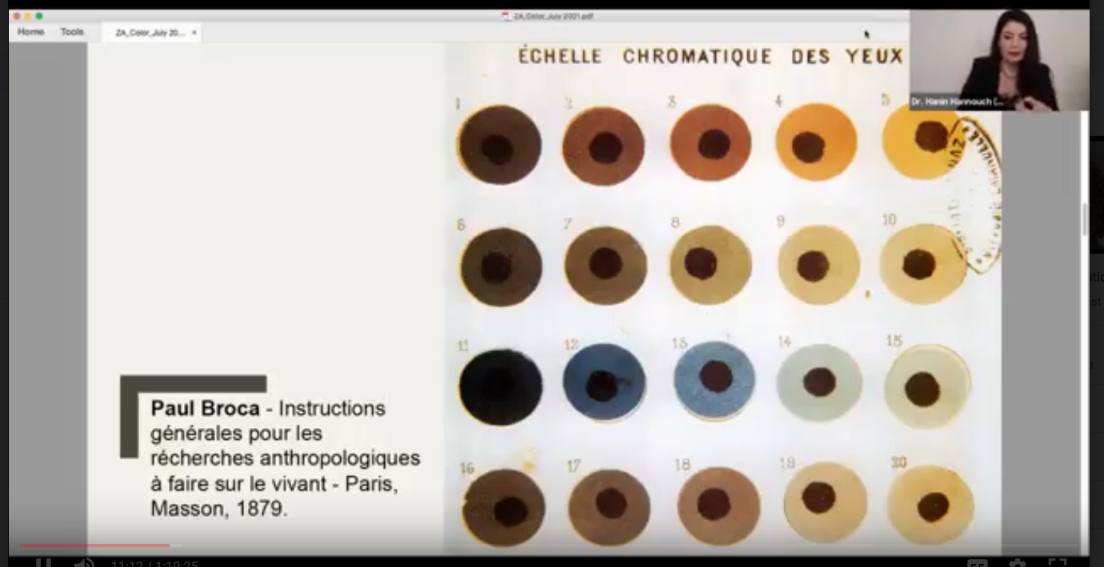

Dr Hanin Hannouch begins the talk with quite an unexpected introduction on the complexities that come with harvesting the human eye. It is strange, uncomfortable, and incredibly provocative. But it is also necessary. It begins to shape the human cost involved with the advent of the photographic project, the colour industry, and Fritsch’s scientific preoccupations. She also spoke of the conditions in which the underprivileged worked in these colour producing factories, conceptually creating a link between the capitalist manufacturing and reproduction of colour products and the loss of life resultant from it.

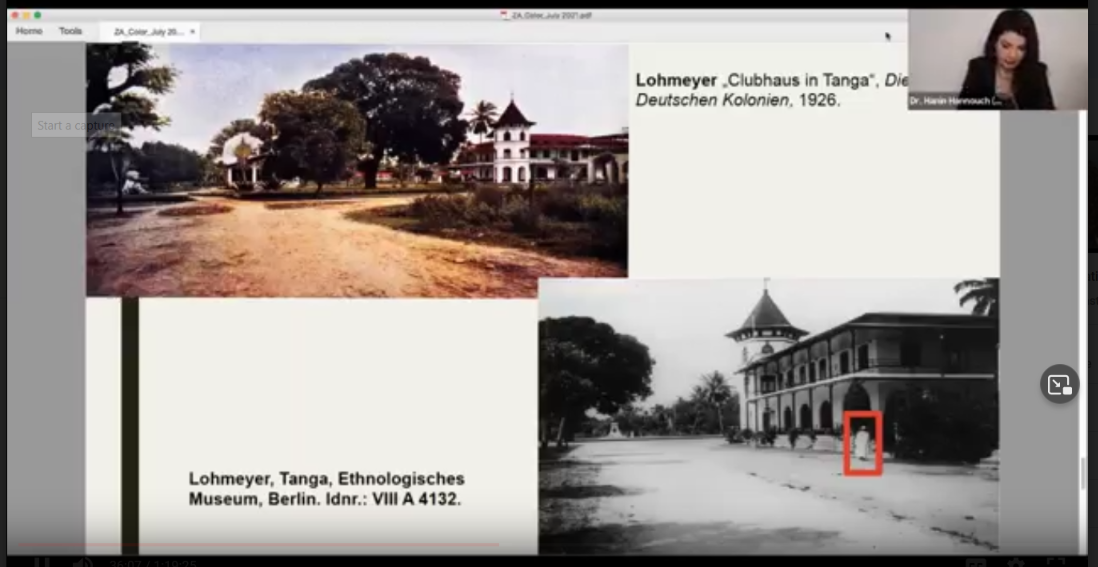

The camera has often been a menacing instrument. There is a long and deep history of the ways in which it has been used to image the world in such a way that allowed colonial powers to study it, profit from it, and own it. By the late 1840’s, photography had become crucial for justifying European domination, playing an incredibly important role in administrative, missionary, commercial and scientific endeavours (Cole, 2019). After completing his medical studies in 1863, Fritsch travelled through southern Africa on a scientific expedition to study the ‘native’ races, taking portrait images of political prisoners on Robben Island and indigenous peoples across southern Africa during a period of colonial domination on the continent. The intellectual and historical entanglements of the camera also flow through the Bleek and Lloyd archive. Bleek’s theoretical concerns led him to participate in Thomas Huxley’s anthropometric photographic project, where they photographed the prisoners of the Breakwater prison of South Africa in conformance with criterion established by Huxley for photographing human ‘specimens’ (Bank, 2006). During this time Bleek corresponded directly with Huxley, a scientist who viewed photography as an indispensable tool for the collection of accurate anthropological data (Bank, 2006). Under the colonial project, and with the advent of photography - nothing would be allowed to remain hidden from the powers that be.

View the discussion, here.

Sihle Sogaula (b. 1993, eQonce) is an Honours in Curatorship student at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. She is interested in fashion as cultural phenomenon and how it becomes inextricably implicated in the construction of group and individual identities. Her current research is an exploration into the ubiquity of the fashion moment in contemporary South Africa and its remarkably ordinary presence in daily life. By reading South African fashion and its representations as text, Sogaula wishes to explore the ways in which meaning is inscribed on the body, and how social subjects reimagine binary constructions of identity.