Weaving 26 - November 2021

This session considered the question of 'Weaving', as an open-ended term referring to the practise of tying together, in this case, histories as materialized in textiles that are incorporated into museum and heritage settings. We hosted Magdalena Buchczyk, whose talk titled, 'Curated Textiles,' explored how curatorial knowledge inflects material practice - see her project in 2021 with the Humboldt Foundation, here. Focusing on the turbulent history of Eastern European textiles from the Museum of European Cultures (MEK) Berlin, the session investigated how knowledge production about textile culture is entwined with history, politics, art practice, curatorial storytelling, and the making of places and people in Europe. This raised wider questions about textiles as curated objects, not only in the space of the museum or archive, but also at the different stages of their making. In the South African context, “[c]ounter-narratives emerge, pointing to ways that an outwardly colonial heritage site is key to exploring multiple, intersecting social roles and relationships,” an excerpt from David Morris’ “Diamond Town Toil and Trauma: Weaving Material Counter-Narratives of Kimberley's Pasts,” (2021).

Further reading:

Buchczyk, M. (2021). Transforming legacies, habits and futures: reshaping the collection at the Museum of European Cultures. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(6). 563-577.

Günel, G., Varma, S., & Chika Watanabe, C. (2020, June 9). A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography. Member Voices, Fieldsights.

Musiza, C. (2022). Weaving gender in open collaborative innovation, traditional cultural expressions, and intellectual property: The case of the Tonga baskets of Zambia. International Journal of Cultural Property. 1-18.

Unruh, L. (2015). Dialogical Curating: Towards Aboriginal Self-Representation in Museums. Curator, 58. 77-89.

Speaker Bio: Dr Magdalena Buchczyk is a Junior Professor of Social Anthropology at the Institute for European Ethnology working across CARMAH and HZK (Hermannn von Helmholtz Centre for Cultural Techniques). Her work focuses on material culture and critical understandings of heritage with reference to collections and making. Her research interests extend into questions of knowledge production, materiality, politics and affect. She has conducted long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Romania and the UK, as well as projects in Italy, Germany and Poland. She joined the HU and CARMAH as an Alexander von Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellow (2019-2021) after a postdoctoral project on learning cities at the University of Bristol. Originally trained in anthropology and critical heritage studies (UCL, Goldsmiths), she previously taught at Goldsmiths, Bristol Doctoral School and Imperial College London. She is currently teaching applied museum and collection research (in collaboration with MEK) and anthropological perspectives on visual and material culture. She also currently helps to coordinate the TRACTS network: Traces as Research Agenda for Climate Change, Technology Studies & Social Justice (COST Action 20134, 2021 – 2025).

Discussant Bio: Lebogang Mokwena, Phd candidate at The New School for Social Research, New York, acts as the discussant for this session.

by Nicola Wells

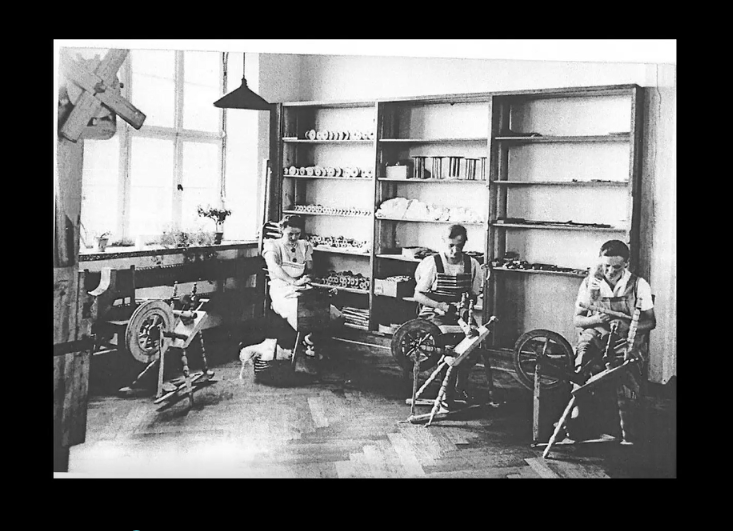

The Spirals talk “Weaving” by Dr Magdalena Buchczyk explored the historical ethnography of the textile collections at the Museum of European Cultures (MEK) in order to tell a story about the museum throughout the 20th century. The case study which Dr Buchczyk focused on for her presentation was that of the woven carpets (Masurian weaving collection especially) which she uses as an example to explore the following question: what would happen if we took the notion of weaving seriously in our thinking about museums?

The double-woven Masurian carpet case study which she speaks to begins with the East Prussian carpets which were acquired in the 1930s by the director of the MEK Konrad Hahm, who also produced a publication on the techniques and designs of the carpets. He argued that the techniques used were Germanic and vastly spread across the Baltic. These ideas would later be used as one of many arguments supporting German occupation of these territories and justified the take-over of Europe as valid. The Masurian collection of carpets originated in the town of Lyck which was once part of Prussia and is now located in Poland. This location becomes important as the weaving practises here thread through time; beginning with the wealthy, local elites who initially owned the carpets in the late 19th century. There was a revival of the practise in the 1930’s following the end of WWI as a means of economic stimulation and particularly in 1939, this revival was seen as a preservation of German nationalism through promoting interest in this craft.

Dr Buchczyk concluded here that she hoped this case study showed how it is important to problematize ideas of this timeless, fetishized idea of folklore and that there is so much more to be seen below the surface when one examines history through the lens of weaving as knowledge production. Lebogang Mokwena then spoke on how the presentation gave a fantastic roadmap on how to use this metaphor of weaving to go further into analysis of museums—that it demonstrated the operationalising of theory. She said it allows for contextualisation and the inclusion of historical, economic and political processes to be a part of the discussion which was a point I agree with entirely.

Dr Buchczyk’s work was inspiring and opened my eyes to the potential of the weaving metaphor as a means of knowledge production in many disciplines and as a form of analysis which will be of great value to museums in the future as they address their own collections and the stories they tell through exhibitions.

View the session, here.

Nicci Wells is an Honours in Curatorship student. She completed her Bachelor’s degree in Archaeology and Classical Studies in 2019 and BA Hons Archaeology in 2020 both at the University of Cape Town. With this background she has always had a fascination in objects and artefacts and their histories in the lives of people. She is especially interested in the disconnect between the archaeological discovery process, how it creates an archive and how that archive is then inaccessible to the general public. She wants to bridge this divide in the future making the information gathered by these processes accessible to everyone, especially those whose history is being studied and written about without them even knowing about it.