Posted on November 17, 2011

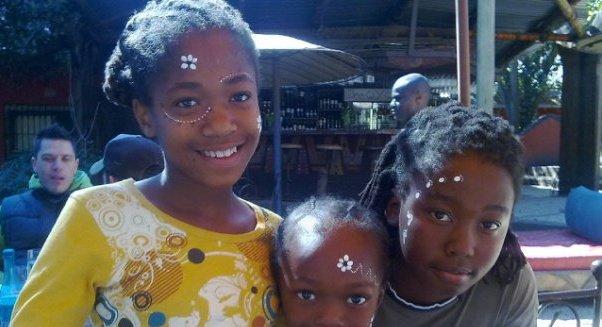

Although my children are the so-called born-frees, they do encounter prejudice in the playgrounds at school and elsewhere. This usually entails essentialised notions of culture, language and beauty that are imposed by their peers. Although some of the playground commentary can be a result of curiosity, it can get uncomfortable when classmates try to touch or ask whether the hair gets washed. This has resulted in my older children wishing that they had straight hair like 'everyone' else as they feel that their natural hair always draws attention, both negative and positive. This to me is evident of just how politicised and racialised hair is, even in the post-apartheid playground. However, this has also forced me to question my own positioning in terms of how I've also been essentialising 'natural' hair, by not allowing chemically processed hair in my household. The rules are simple: you want long hair, grow dreadlocks or an afro, should this be a problem, then shave it all off. My children's paternal grandmother disagrees because as a respectable member of her community, her grandchildren's hair has to be 'neat', in other words, straightened. In her view 'good' hair is also indicative of one's socio-economic status and as the children of the new black middle class, the children must look the part.

Fourteen years ago, I started twisting the twins' hair into dreadlocks; the process was both emotional and spiritual, it was symbolic of my own struggles as a young single mother. My thoughts, meditations, wishes, dreams and visualisations were weaved into my children's hair, while my own processed hair was cut off and replaced with an afro. I always think of this moment as a major turning point in my life, the beginnings of my new role as a mother and it is symbolised by the marked change in the way in which I choose to wear my hair. Over the years, I've also grown dreadlocks, cut them off only to grow them all over again, and I am now completely bald. My children too have gone through various stages, with their grandmother cutting off the dreadlocks and putting hair straightening cream and me shaving it off in reaction to her actions. This has been going on for the past few years, with the children's hair being the site of contestation between myself and the children's paternal relatives.

According to Kobena Mercer (1987), the symbolic value of hair is perhaps clearest in religious practices – shaving the head as a mark of worldly renunciation in Christianity or Buddhism, for example, or growing the hair as a sign of inner spiritual strength for Sikhs. Beliefs about gender are also evident in practices like the Muslim concealment of the woman's face and hair as a token of modesty. Mercer argues that such practices socialise hair, making it the medium of significant "statements" about self and society. My rejection of processed hair is indeed indicative of me making statements about being black in a still largely untransformed South Africa, and the imposition of such statements on my children is to ensure that they grow up knowing that there is nothing wrong or ugly about themselves or their hair. However, such statements are not limited to hair, they extend to language, and even ways of understanding the world. Besides, in any household, there are basic rules and values that children cannot learn at school and for us, these happen to involve hair. Naturally, there is a tendency to rebel, however, in my view, as long as dominant notions of seeing the world persist, there is still a need to deconstruct them.

We still need a historical perspective on how economic, political and psychological values have been woven into the complex texture of our 'kroes' hair. As long as such historical perspectives are not engaged with publicly, I will continue to illuminate them in our private space. This of course might be flawed and subject to criticism but I also believe that there is no template or formula for parenting, it is largely trial and error, with the hope that the children will grow up to become self-appreciating adults. They might decide to process their hair as soon as they leave home, however, I believe that I would have at least given them an understanding of the complexities of difference that are associated with our history. Such an understanding is important for the present and also for the future.

My children, Lulibo, Phatsimo and Thuto

Sources: Mercer, K (1987) "Black Hair/Style Politics". New Formations, 3