Navigating the 54th Venice Biennale

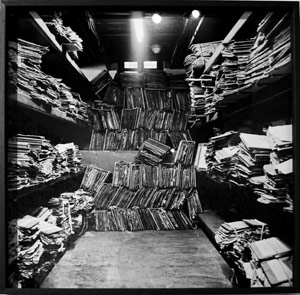

Dyanita Singh's File Room (2011) is a gridded installation of tightly cropped monochrome pigment prints of a room filled with files and then forgotten as time rushes on outside

PICTURE: BRENTON MAART

From Zhang Dali to Thomas Hirschhorn, BRENTON MAART examines several archive-driven projects at one of the world's most substantial contemporary art exhibitions

I trek across the expanse of contemporary art that is the 54th Venice Biennale. ILLUMInations, the key exhibition curated by Bice Curiger, sprawls densely over two venues: the Arsenale (founded nearly a thousand years ago as the city's maritime centre, a place so consumed by fire, iron and pitch that Dante used it as a model for hell in his Divine Comedy), and the Giardini (the Napoleonic gardens now home to the Biennale's 28 national pavilions that, collectively, form a motley compendium of 20th-century architecture).

Further afield within the lagooned city - once the 'Pearl of the Adriatic' - are hidden the pavilions of more than 20 other countries, supplemented by more than 35 collateral exhibitions. Demanding additional tenacity of the dogged visitor is a myriad of museums offering their own curated shows. This is a lot of art, made by more than 1 000 artists, which, at a glance, might present a sweeping overview of contemporary visual culture.

For this text, I describe six projects that use methods of collecting, curating and archival practice to steer creative and intellectual production. The text also pays close attention to the nuances between form and content, in an attempt to understand the projects' trajectories. A key focus of contemporary critical practice is the promotion of archival agency, and the text examines each project's contribution to this objective.

The case of truth, lies and the tampered archive

On Speech Matters at the Danish Pavilion, curator Katerina Gregospresented the work of artists from 12 countries that explore the contested terrain of freedom of speech. The exhibition - which avoided the didactic through a nuanced balance between politics and the visual - held significance not only to the South African battle for access to information, but also internationally, and the curator notes the works' direct responses to increasing press censorship in Russia, the embargo of Google through the 'Great firewall of China', suppression of voices in many North African countries, changes to media law in Hungary, the WikiLeaks scandal, increased surveillance in the UK and the USA, and highly charged debates about the limits of freedom of speech in several European countries.

Of specific interest is the work of Chinese artist Zhang Dali. Titled A Second History (2010), the work was initiated in 2003 when the artist started constructing an archive of photographs published during the reign of Mao Tse Tung. Through meticulous research at publishing houses across the country, the archive was extended using magazines and books, albums, newspapers and archival material not accessible to the public. Further, the artist located the original negatives, from which she made prints. Adopting a forensic approach in order to compare the original with the published images, Dali was able to track the changes that were made to the original material, in their transformation to the published 'official' images.

The work on the Biennale juxtaposes the original with the 'doctored' photographs and the alterations are startling: dilapidated houses of poverty transformed into middle-class apartment blocks; farms given an air of prosperity through the addition of fields of grain or increased herds; leaders moved to locations steeped in the iconographies of power more suited to managing their public image; empty fields populated with rows of productive happy workers; banks of political opponents or threats removed through airbrushing.

The project is endlessly fascinating, on many different levels. It is a reminder of a political era built through social manipulation. It demonstrates the methods of both the writing and the rewriting of history, and it maps the relationships between politics, history and its narratives.It is a story of truth and lies, and the management of slippages between them. It is an examination into the fabrication of memory. Importantly, it is presented as a historical case study that may still be ongoing, and may arguably be extrapolated into other countries. And finally, it is an indisputable reminder of the formative power - of, amongst others, the agency to construct political giants - that is vested within the archive.

Drama in the file room

The analogue materials of paper and parchment, wax audio recordings, photographic and moving image film are some of the earliest forms of physical archive. Subjected to physical wear and tear, the passing of time heralded even further indicators of decay