Under-utilised archive could shed light on the emergence of the modern African art canon

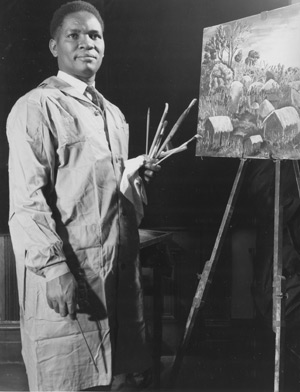

Sam Ntiro, an image produced by the Harmon Foundation for promotional purposes in 1960, from the Harmon Foundation archives, National Archives, Washington DC

By Mario Pissarra

I first became aware of the Harmon Foundation, a philanthropic organisation that played a key role in supporting African-American and African visual artists, in the course of research for my PhD. I was trying to find information on Sam Ntiro, a seminal but poorly documented figure in East African art. Evelyn Brown's 'Africa's contemporary art and artists' published by the Foundation in 1966 was the first serious book on the subject, an unprecedented survey of modern African art, notwithstanding its limitations as a 'sub-Saharan' study.

When in 1967, 45 years since its establishment, the Harmon Foundation closed its doors it granted its archives to several public institutions. Its official records are in Washington DC with visual material, mostly photos and slides housed at the National Archives at the University of Maryland, and correspondence, press clips and other documents at the Library of Congress. The art collection went to Hampton University, Virginia and Fisk University, Tennessee.

Most of the Harmon Foundation archives have never been digitised, and are an under-utilised resource.(Among those who have made good but select use of the Archives are prominent scholars Simon Ottenberg and Sylvester Ogbechie.)The National Archives have published online a select list of artists from the collection, and it is possible to order prints of images by these artists. The Library of Congress has published a Finding List online, which identifies in broad terms the contents in their collection.

In December 2011, I was fortunate to visit Washington DC to launch Visual Century, a four-volume history of South African art published by Wits University Press. While there, I spent a few days frantically copying information from the Harmon archives. The process was both stimulating and frustrating.

At the National Archives I found no less than 45 colour slides of Ntiro's paintings, along with black and white photographs of an additional 15 paintings. The works were from the late 1950s and early 1960s, the peak of his career, and almost all have never been published. If you consider that it has (somewhat dubiously) been claimed that only 40 of his works have survived, and that I have only seen images of less than 15 works, you may appreciate how significant this find was.

To copy these slides would have cost me $8 each, which I could not afford, and without the benefit of proper viewing facilities, choosing a select few was no option. All around me researchers were merrily scanning with their own equipment, while I could only wonder what if...

I had also picked up reference to a scrapbook, which I did not find. And at the Library of Congress, time constraints meant that I photocopied every letter written by Ntiro, but not those written to Ntiro by Evelyn Brown, leaving me with half a conversation. Clearly I had to return, but how?

One year later - this time via a conference detour in Philadelphia - I was back in DC for another flying visit. My primary objective was to scan the Ntiro slides at the National Archives, and it almost never happened. I won't bore you with what I went through trying to secure myself a functional scanner as the slide duplication service is no longer operable at the National Archives, except to assure you that I spent a disproportionate number of days fighting scanner wars. But in the end my perseverance paid off.

I had budgeted five days for scanning and these proved to be very full indeed. Three were spent at the Harmon archives, and two at the Warren Robbins Library at the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution - the undisputed premier library for information on art in Africa. I managed to find Ntiro's scrapbook, and this was useful both because it contained photos of paintings no longer in his file, as because it provided evidence of how the Foundation compiled information on individual artists in order to promote them in the USA.

I had very little time to look at anything without Ntiro's name on it, but what I did glimpse highlighted the potential of the Harmon Foundation archive in shedding new light and perspectives on the development of a critical discourse in modern African art. For instance, I came across reviews written by Francis Msangi in Tanzania in the early 1960s where the writer (an artist) articulated many of the critical postcolonial discourses associated with the late 1980s and 1990s.

One can also gain candid insights into the minds of many of the artists active in the 1960s, not least because Brown clearly established good relations with many of them, and this is evident in sometimes candid reflections in their correspondence. Brown worked in an inclusive manner, guided by her interest in documenting contemporary practice, and many of the files concern artists who were never written into subsequent surveys. Whereas one of the features of early studies is the repetitive range of artists, the Harmon archives provide a rare, panoramic view of the field, without being wedded to the particular concepts of authenticity operative in later surveys.

The importance of the Harmon Foundation archives in rethinking the canon and its emergence becomes evident when one considers some of the material it contains. I was particularly struck by images in the file of Louis Mwaniki, a Kenyan artist who studied at Makerere. Generally, early surveys of modern African art provide little evidence of politically engaged work by Africans during colonial rule, more especially in work from East Africa, which is typically described as being heavily influenced by the tourist market. Imagine then my surprise in coming across photos of Mwaniki's Emergency series from the 1950s, which documents settler atrocities. These works appear to have been too 'literal' or descriptive for the tastes of Ulli Beier and other influential chroniclers.

A similar observation can be made of the illustrative style of Akintola Lasekan. Lasekan has fared better than Mwaniki in art history, being acknowledged as one of the early modern Nigerian artists, modestly represented in surveys through imaginative, semi-naturalistic images of Yoruba folklore as well as fairly lifelike portraits. Lasekan's file in the Harmon archives provided ample evidence of a strong documentary impulse in his work.

Most examples were detailed representations of everyday Yoruba life, and at least one commemorated a historical moment in the anti-colonial struggle. The works by Mwaniki and Lasekan demonstrated the possible existence of a counter-canon, one in which realist modes of representation, storytelling narratives and anti-colonial sensibilities produced a politically engaged art that was overlooked in most early studies

From a South African perspective, it was interesting to see that unlike Beier et al who skirted the Republic in their surveys of modern African art, Brown found ways of penetrating south, presumably through using alternative ('non-establishment') networks. Some of the South African artists featured were exiles such as Gerard Sekoto and Selby Mvusi. But most were resident within the country and were not well known figures at the time, although some, like Peter Clarke, would later become important figures in South African art history.

However the majority are little documented or known, such as James Mitchell, a skillful printmaker. There is also a photograph of an enigmatic naked male figurine with what looks like a springbok's head carved by one Horatio Mavuso of the Ndaleni School in 1962 - 18 inches high and yours at the time for R36, quite possibly one of the earliest hybrid beings sculpted by a South African artist.

On my return, I went back to the online information published by the National Archives and Library of Congress. The overlaps and gaps can be confusing. The Library of Congress finding file includes folders on Mwaniki, Lasekan and Mavuso, but the information (images) I refer to above is not at the Library of Congress but at the National Archives.

The information published by the National Archives does not acknowledge files on these artists. Instead they provide you with a select list of artists whose works, as indicated earlier, are not in their possession, but rather in universities in neighbouring states. The absence of references to Mwaniki, Lasekan or Mavuso among the artists of whom one can buy prints from the National Archives may mean that they were not purchased by the Harmon Foundation, or that they were not considered important enough to document. Either way, their marginal status is affirmed, not only outside Brown's study, but within the Harmon archive itself.

This observation of layers of exclusion and marginalisation highlights the need to physically engage with the Archive, particularly for the sake of those artists who, in retrospect, may have been a lot more interesting than was recognised at the time.

Mario Pissarra is a PhD candidate in Sociology, UCT, and an affiliated researcher of the Archive and Public Culture research initiative. He travelled to the USA with the support of a UCT conference grant, a UCT research associate award, and an ad-hoc grant from the APCRI. Special thanks are due to Janet Stanley, librarian at the National Museum of African Art, whose hospitality and assistance made both research trips to Washington DC possible.