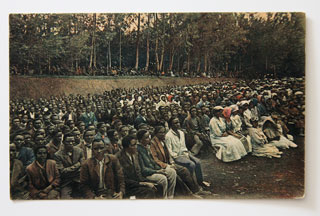

In search of Balobedu, a research trip to the Evangelisches Landeskirchliches Archiv in Berlin

'Missionfest in Medingen' from the series: Nordtransvaal I

(Süd Afrika) Nr. 24, published by Berl Publishing house, date unknown (circa 1907-1933)

By George Mahashe

In 1881 a missionary named Rev Fritz Reuter set up shop in Bolobedu, in the north-eastern part of the Boer republic, Transvaal (now North Eastern Limpopo, South Africa). Reuter had been invited to Bolobedu through one of Rain-queen Modjadji's nobles, Kgashane Mamatlepa (jr).

Together with other young men, Mamatlepa had been sent by Modjadji to Port Elizabeth to acquire firearms. During the course of their mission, Mamatlepa made friends with a convert in the area, who introduced him to the Christian gospel, leading to his eventual baptism. On his return to Bolobedu, Mamatlepa brought back with him the firearms as well as the bible, and quickly began to share the gospel with those who would listen, eventually requesting a missionary to be sent to Bolobedu.

Although Reuter was the first missionary to successfully start a mission in Bolobedu, his parent missionary society - the 'Society for the Advancement of Evangelistic Missions Amongst the Heathen',which was later called the Berlin Mission Society (BMS) - had been in the region since 1860, being among the first missions to bridge the northern Transvaal. Reuter's entry into the area immediately put him at odds with the area's religious order. Courting the wrath of Modjadji II several times, he eventually fled to Alexander Merensky's mission station, Botshabelo (place of refuge).

Over time, Reuter proved to be a useful mediator between the Boer republic and Modjadji - mediating to avoid a war, as well as assisting Balobedu during the 1894 drought. With his newfound position, he was invited back to Bolobedu and given a piece of land just 15 km from Modjadji's capital. His congregation grew in numbers. In 1897, Reuter arranged for a mixed group of 60 Balobedu converts and 'heathens' to travel to Germany for the Transvaal exhibition.

Over the last few years I have developed an obsession with the German missionaries and their exploits in southern Africa. As my awareness of their influence on black, as well as white, South Africans' education grows (along with an awareness of how this influence impacted on the trajectory of apartheid and today's efforts at dismantling its remaining institutions), I cannot help but wonder what things might have been like when they first moved into the area. I try to imagine their negotiation of the area before their romantic transgressions set in motion events that would influence South Africa so deeply. And ask myself how they managed to stay on neutral terms with both the Boer and the indigenous population?

Through my research into Balobedu, I have come across stories and rumours about the relationships between Balobedu and Reuter - their entangled nature. One of my favorite rumours talks of a group of men who where part of Reuter's 1897 delegation to Germany. These men are said to have been spies sent by Modjadji to survey Reuter's world. As a photographic researcher, I couldn't help but wonder if there would be any photographic traces of such an excursion in the mission archives. Perhaps I could find the oldest - or even the first - photograph made in Bolobedu.

My involvement with the Michaelis School of Fine Art's Between the Lines symposia presented the perfect opportunity for me to do some digging. (An academic and artistic exchange initiative between South Africa's Michaelis School of Fine Art and Germany's Braunschweig University of Art, Between the Lines culminated in two symposia - Cape Town and Braunschweig - as well as two exhibitions - Cape Town and Berlin - as part of the German/South African year of science 2012/2013. The initiative's core theme revolved around issues of translation, particularly in reference to artistic practice and theorisation.)

With this opportunity to travel to Germany, I decided to add an additional week to my itinerary so that I could start my journey into the German missionary's exploits in Bolobedu. With weeks of preparatory emails, back and forth, trying to establish contact with a person at the archive, I finally made contact with Dr Ulrich van der Heyden, who had published a great deal of historical material on the Berlin Mission Society, as well as on Reuter's time in Bolobedu.

I finally landed in Germany on a chilly Thursday morning. Ready to dig in, I attempted to call my contact's office only to learn of his sudden illness, which had completely incapacitated him. There I was, ready to go with no contact and no way of getting into the archive. The email and telephonic contact detail for the mission archive in my possession were outdated. I was rescued by my attendance of a conference event on another BMS missionary, Carl Hoffman, hosted by the South African scholar, Dr Annekie Joubert, who kindly introduced me to the director of the Evangelisches Landeskirchliches Archiv, Dr Krogel.

Dr Joubert's event was part of the German/South African year of science held at the South African embassy in Berlin. Its aim was to present some of Dr Joubert and her team's research findings as well as the airing of a documentary project relating to their missionary's journey into South Africa. The panel taking part in the discussion consisted of a variety of specialists in theology, linguistics and library services, all concerned with the archival legacy of the German missionaries in Africa. A key debate revolved around the possibility that digitization presented to inter-university archival scholarship, and the role of translation in making the archive accessible to all stakeholders across the different languages involved.

There was also a curiosity expressed by the panel about the role and position of the visual material within the mission archives, but this area of research was not yet fully developed within the German mission archives' research areas. At the end of the event, a volume of Hoffman's personal diaries translated from German into English by Dr Joubert's German/Sotho students, as well as digital copies of selected mission files from UNISA's archives and the Berlin archives were exchanged. Here, I met a variety of South African and German scholars as well as administrators who were engaged with the German missionary archives at various institutions.

My introduction to the mission archives director got me on to a scheduled tour of the mission archives, where we were taken through the different facilities used to house the various archived objects, including a demonstration of the retrieval system used to access the digitized collection as well as an explanation of the digitisation process. The state of the archival system as a whole was rather impressive, everything had been thought of, from the building design, to the digitization workflow, the environmental control system, all the way to the protocols followed for moving the requested archival material from cold storage in the basement levels to the viewing rooms on the upper floors. The archive was indeed well funded and well conceived. I look forward to such systems being implemented in South Africa.

The afternoon was concluded with a lunch and some casual discussions around administrative differences between South Africa and Germany, dwelling for a long time, on how South Africans tend to put the important details at the end of an email, choosing to open with pleasantries - a point of frustration for their German counterparts, who would prefer to get the reason for the email first.

Despite the headways I had made in making contact with the mission archives, I was still a long way from getting into the archives. My efforts to access the visual material on the northern Transvaal missions, which I had just briefly looked at in cold storage, was denied on the basis that I had not made sufficient arrangements for the proper protocol to access the material. I was given the right contact details and asked to send an email.

I got to my hotel and immediately wrote the email, attaching all previous email correspondences and hoped for the best. All I had was two more weekdays before I was expected to start attending the Between the Lines symposium. At five minutes past five on the Friday afternoon I rang the archive and managed to secure tea with the director for Monday morning, hoping for a chance at taking a closer look at a file of photographs from Reuter's mission station. We met on Monday, had some black tea and exchanged stories about missionaries, Balobedu and artistic research interest in the mission archives, while we waited for the file to adapt to the temperature on the 2nd floor.

When I looked through the visual material, I was excited beyond my imagination. I was peeking into a missionary's exploits into Bolobedu at the cusp of the 19th and the 20th century. I did not find any evidence of Modjadji's spies - at least not yet - but I had made first contact. Today as I look at the photographs I copied against the background of some English readings I have since found on the BMS and Reuter's exploits in the Transvaal, an exciting world begins to emerge, my understanding of the colonial encounter sharpens, and the pull of the inconsistencies becomes even stronger. Archives hold many treasures, but the real treasure is the network of scholars that peruse them. Making contact with some of them was the most exciting aspect of my trip.