Finding a (Path)way to Digitise the Past by Ettore Morelli

Throughout the year, the Five Hundred Year Archive team has been busy trouble-shooting our first online archival exemplar, now live at https://fhya.org. The incredible variety of materials that are convened on this platform in a digital form inspired us to further experimentation. There is a lot on the boil.

In this piece, I focus on one aspect of a larger innovation I have been personally involved with, the creation of an interactive essay for the presentation “Exploring uMgungundlovu”. I speak here about “A Small, and Scarcely Perceptible Pathway to uMgungundlovu”.

I am not a specialist of KZN history. I have been working for a few years on the precolonial, late-independent history of the Highveld, from the Maloti Drakensberg to modern Botswana. Of course, the people I study often decided to move beyond the geographical limits I set for my research, pulling my view a bit further afield. This was the case of two brothers I read about some years ago in the Africa and Asia Reading Room of the British Library: in the late 1820s, they left the Highveld and settled near uMgungundlovu, the residence of the Zulu king, Dingane, in a village of “Bassoutos”, and became traders. At that time, I did not make much of this information.

This changed when I joined the discussion on the materials the FHYA had digitised about uMgungundlovu. Immediately, this marginal note in my research acquired new meaning. Speaking with the other researchers revealed its potential. This community of “Bassouto” traders near uMgungundlovu was something unheard of. We started to think about creative options to develop on this scrap of historical information.

The story is contained in a handful of published French sources, some of which are known to scholars through their 19th-century English translation, but which are mostly inaccessible in their original form, because of the language barrier. I first offered to translate the most substantial piece, the obituary of one of the two brothers, a document narrating in some detail the journeys he made during his youth and his turbulent experience as subject of Dingane. Then, we decided to upload all these French sources, and their translations, to our digital archive. I started to write the content for a brief presentation that quickly grew in a more detailed essay on the route that connected Thaba Bosiu, the capital of Moshoeshoe, to uMgungundlovu.

Translating a source is an ordinary activity in historical research. Sharing the translation is also quite common, as is sharing the source itself, both actions pertaining to what in the traditional editorial world falls into the category of editing (a source, a book). However, some of these French sources were highly visual, allowing us to explore more fully the potential of a digital format. One of them became the centre of the essay I was writing.

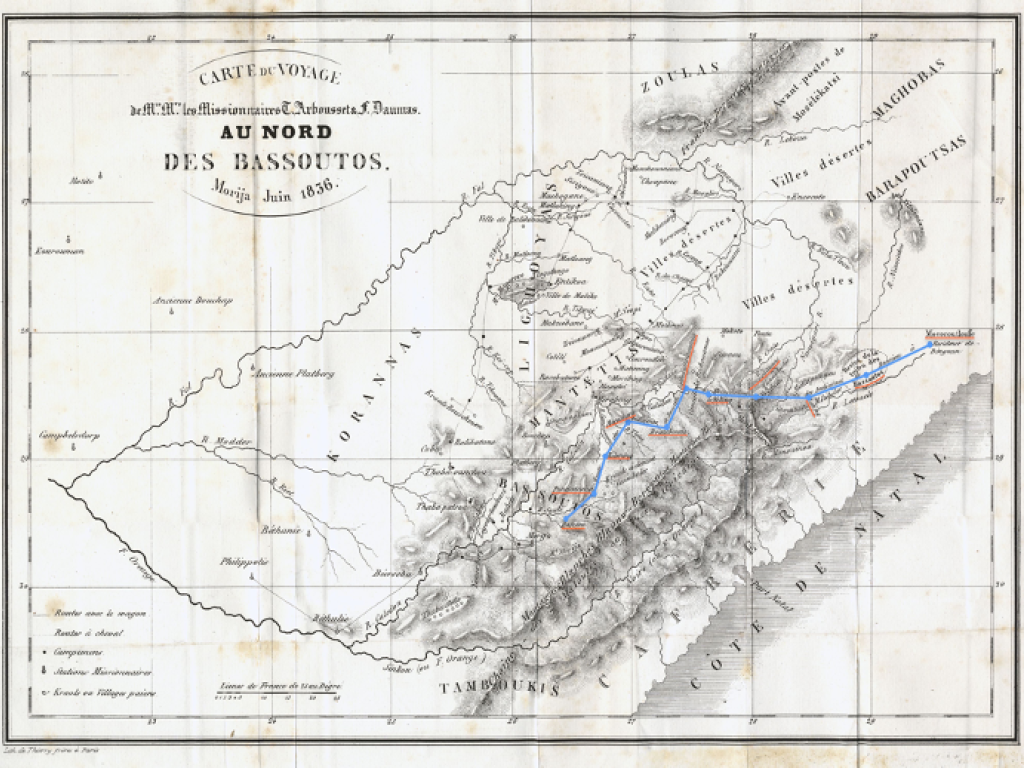

This source is a map. It was drawn in June 1836 by a French missionary, Thomas Arbousset, after he and a colleague spent some months exploring parts of what is today Lesotho and Free State province. The map was then published in Paris in a missionary periodical and was included in the book containing the travel account that was published by the same missionary in Paris in 1842. This map is a precious historical document that merits close attention. For the essay, the most relevant aspect of the map is the fact that it contains the route that African travellers walked to get across the Drakensberg from Thaba Bosiu (in Lesotho) to uMgungundlovu (in what is today KZN). The theoretical opening here is significant: the missionary did not explore all the sections of the route, but collected information about it. This is the only colonial map I personally know of where sinuous route trajectories do not stand for the movements of European explorers, but for African travellers. Writing the essay has therefore opened up two concurrent paths. On one hand, I am preparing an article about the French map and the African travellers for scholarly publication. On the other, I am involved in developing an interactive presentation, centred on the map itself. Two different paths to the past, for slightly different audiences, both viable, both incomplete without the other. A preview of the work-in-progress version of the “A Small, and Scarcely Perceptible Pathway to uMgungundlovu” is available at https://fhya.org.