Thinking with the past: APC Research Development Workshop May 2021

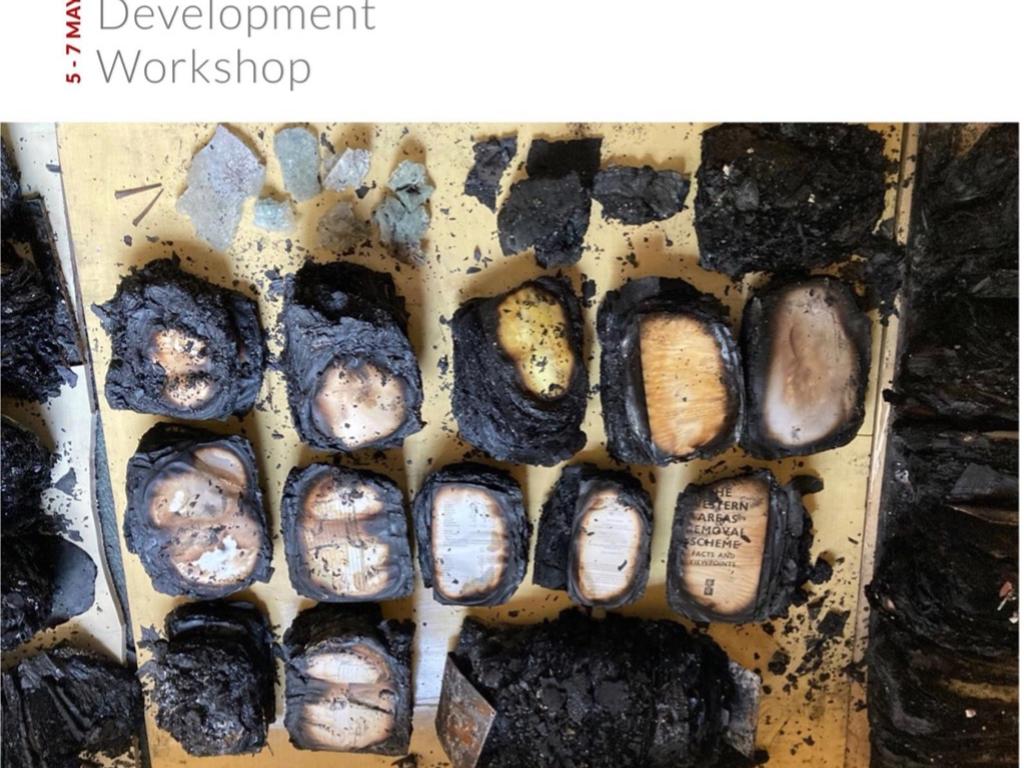

The APC’s first Research Development Workshop of 2021 took place from 5 to 7 May on Zoom, in the aftermath of the Table Mountain fire, and in the midst of efforts to salvage materials from the Jagger Library. The fire, and the questions it has since provoked about archives, loss, the transformation of collections, and scholarly obligations, would be inescapable for this workshop. Holding this in mind, the APC drew upon a photograph taken by APC associate researcher Jo-Anne Duggan of a series of charred remains of books from the collection, using it as a visual point of reference throughout the workshop.

Following the model of the past year’s two workshops, 33 papers by 34 authors were read, given written commentary by assigned commentators, and discussed collectively over 12 flash sessions led by Flash Drivers who drew out questions from these many conversations that would reverberate across the three days of the workshop.

The first day’s papers were broadly focused on the past, and the problems that follow from trying to reassess it. The first session opened with a paper from Anette Hoffman, calling for a new engagement with the histories of graverobbing and racial science that shadow the field of linguistics. An urgent conversation followed between the papers delivered by Maanda Mulaudzi and Sanele kaNtshingana on, respectively, the history-writing of WMD Phophi and of Gciniswa Noyi and William Kekale Kayi. These papers and the discussions they raised highlighted the question of how South African history might be critically refounded around the kinds of critical and vernacular relationships to history and the present found in these works. Perhaps, here, a gesture to an APC-ish historiography.

The second session built on these questions, asking us to consider a new mode of positioning subjects who might otherwise be relegated to “citation” as “sources”, to consider the conditions of production of vernacular writing, and broadly to pay close attention to the political and social transformations produced by colonial presence. Ettore Morelli’s paper offered the beginning of an experimental and theoretical tracing of the lives and intellectual networks of African authors writing about the past. Sibusiso Nkomo’s paper followed mission letters to draw crucial links between vernacular print cultures and the missionary, commercial and government publishing that preceded and informed them. Mojalefa Koloko’s proposal asked how Basotho political life has changed in substance and structure from the precolonial period to today, and triggered a rich conversation about the use of “anachronism” in thinking about the past.

From these questions, session three pushed the discussion towards thinking with the past. David William Cohen’s paper invited us to consider what it might mean to position historical actors as coauthors and collaborators, and to think through the trouble of accessing silence, particularly because historical silences are gendered. This latter question would also reappear for Carolyn Hamilton and John Wright’s pair of papers, which offered a methodological provocation to consider texts not conventionally read as “histories”, and an example in their chapter on the politics of Hlubi identity of how tracing modes of account and contestation written in other genres allows a way to understand how history and the idea of history in political life are always in conversation. Session three closed with Henry Fagan’s careful examination of the role of the James Stuart Archive in South African history, and the broader role of archival forms of knowledge both within academic circles and in public life.

The fourth and final session of the day began with Sizakele Gumede’s examination of Harriette Colenso’s political praxis in late colonial Natal. This would come to trigger a lively conversation about how to manage and analyze the way ideas of “tribalism” come to take life in past historical moments. Closing the first day, Angela Ferreira presented a paper on the use of gossip and anxiety as means through which to think identity-making in precolonial Natal.

The second day opened with a conversation and reflection, led by Duane Jethro, on archival grief, obligation, and antagonism in the wake of the Table Mountain Fire. This conversation took us many places, from questions of copyright, the politics of digitisation and image use, to the possibility of making something generative from a context of loss, and the difficulties of sitting with the losses we know of and those that are harder to see.

After this conversation on archival loss, session five pivoted to how visual and narrative archives might help us reframe history, with Athambile Masola’s exploration of the friendship between Frieda Matthews and Pumla Ngozwana, which underscored how the intimate lives of historical figures rendered their public lives possible. Following this, Lesley Cowling presented a chapter analysing the 20th century commercial press in South Africa, exploring how the logic of catering to Afrikaans-reading, English-reading, and black audiences would come to map onto a divided public.

Session six led us through a series of proposals. Debra Pryor presented a proposal for a project considering the index card, and what it might be possible to read through it. Ilyaas Combrink presented on a project that will explore the genesis of the CAPS curriculum and consider what it might mean to push it from a postcolonial to a decolonial frame. Finally, Vanessa Chen presented a further development of her project tracing the Chinese community at the Cape, which opened a conversation about how digital curation can offer a means of relating archives in new ways.

Session seven opened with Richard Higgs’s proposal for a project exploring digital archives and the discontinuities of mediatisation and history. This conversation turned to questions of exemplarity and theorisation, and what one owes to one’s sources. Following this, Carine Zaayman presented on questions of archival authenticity and absence, exploring how the Clanwilliam Arts Project makes “anarchival” sense of the Bleek and Lloyd archive. After this, Heather Hughes and Victoria Araj offered reflections on an institutional decolonisation project at the University of Lincoln, stressing the importance of thinking about how past injustice has present lives and consequences. The session closed with an extended conversation about the contemporary stakes and urgency of doing critical historical work today.

The final session of the day began with Lebogang Mokwena’s paper on museums and knowledge production, which invited us to consider the possibilities for reading multiple levels of relationality that emerge from centering objects – like isishweshwe – in our analysis. Following this, Sabelo Sibiya presented on his proposal for a project examining the historical idea of the Sibiya clan against contemporary readings of it, while also producing a digital curation of Sibiya izibongo.

The day closed with some time for group chat, which opened out to a series of reflections on disciplinarity, what “history” as a field formation trains us to do, invites us to do, and perhaps also disallows.

The first session of the third day of the workshop brought us closer to the present in time. Thandile Xesi presented a paper on the public life of the idea of Contralesa, the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa, and its consequences for the constitution of publics in contemporary South Africa. Patrick Whang presented an analysis of the transition of Basotho politics from being predominantly organised through the chieftaincy to being structured primarily through political parties.

Session ten focused on two quite different sets of debates about the past. Cynthia Kros’s paper explored a series of angry scholarly debates in the Journal of Natal and Zulu History. This prompted a broader conversation about “angry debate” and scholarly authority. Himal Ramji’s paper explored contemporary representations of the Cattle Killing of 1856-7, using these as a way into thinking about prophecy and globality.

The following session opened with a discussion of a piece of isiZulu short fiction by Wade Smit, which invited a return to earlier conversations about the work of translation, the urgency of encountering isiZulu writing in a context like this workshop, and also a parallel conversation on the stresses of research life. After this, Alírio Karina presented a paper from their book project inviting a reassessment of how anthropological discourses come to permeate the history of 19th and 20th century Zanzibar.

The final session of the workshop invited a consideration of sonic and performative ways of knowing. Amogelang Maledu presented on a new project that will examine the music cultures of Pretoria to open out questions about archives, the objects they hold, and the sonic as a field for cultural production. Thokozani Mhlambi’s paper explored the problem of genre and language in defining African performance practices, offering a register of various performance forms not easily reduced to Europeanised ideas of genre. In the final paper of the workshop, Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja mapped out an audiotopia of Namibian struggle music and jazz, inviting us to think the radicalism, travel, and rootedness of past and contemporary Namibian musical forms. The workshop closed with a joyfully curated selection of songs even more joyfully danced by Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja.