Research labs

Alirio Karina

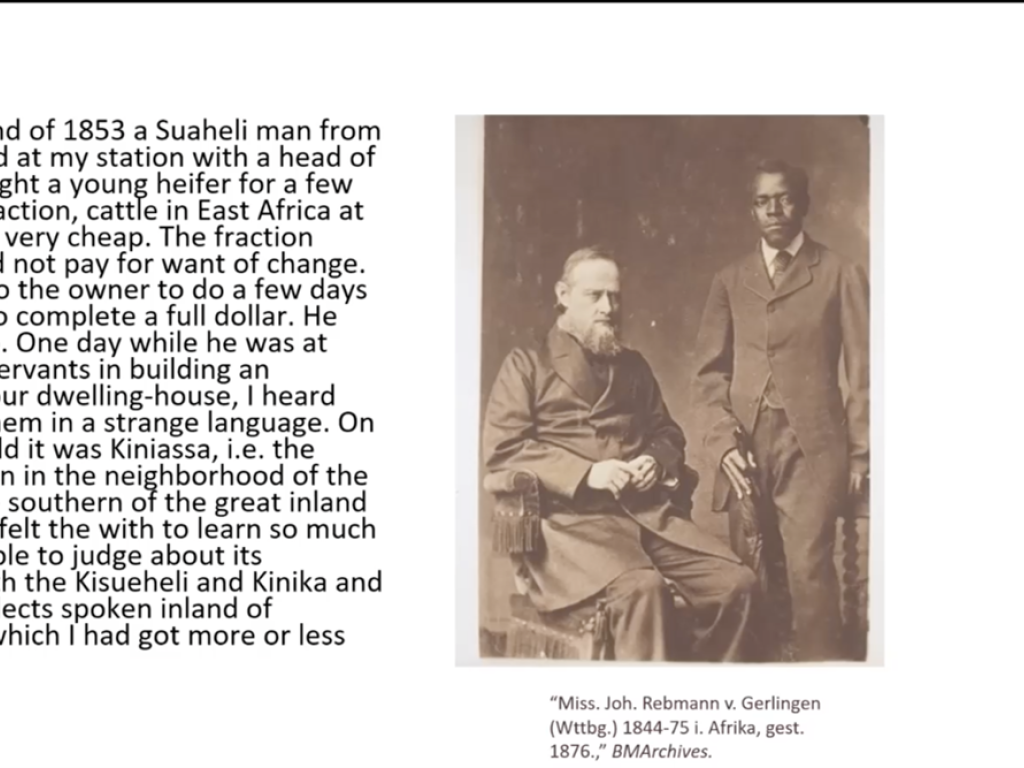

On 30 September 2020 Dr. David Bresnahan, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Utah, presented “Slavery in Translation: Tracing Concepts of Marginality and Belonging between Lake Malawi and Mombasa in the first Nyanja Dictionary”. This paper offered an account of the collaboration between an enslaved man named Salimini and a German missionary, Johannes Rebman, in the making of the first dictionary of Chinyanja. Dr. Bresnahan explored how this dictionary, a deeply idiosyncratic document representing a single person’s sense of the language, offers a unique source for understanding slavery in the Swahili Coast. The particular words in the dictionary demonstrate how Salimini would come to translate Mombasa’s sociopolitical landscape into seemingly singular Chinyanja terms, in ways perhaps reflecting his own efforts to understand his new social positioning. A rich discussion followed Dr. Bresnahan’s presentation, exploring, among other things, the importance of translation, the complexity of experiences of slavery, and the potency of this dictionary as an entry point into otherwise obscured parts of coastal life.

At the year’s final lab on 11 November, Dr. Daren Ray, Assistant Professor of History at Brigham Young University, presented “Muyaka’s Lament: Poetic Memory and the Surrender of Mombasa, 1815-1840.” The paper explored how the work of the early nineteenth-century Mombasa poet, Muyaka bin Haji al-Ghassany, recorded following generations of oral transmission among poets, could constitute a genre of historical account. Particularly, the paper examined Muyaka’s poetic responses to the politics of Mombasa’s slow surrender to the Sultanate of Oman, exploring how they reflected a complex and intimately Mombasan sense of political imagination and attachment, and the drawn out contingencies and allegiances that marked this often-ignored moment of transition. The lively discussion that followed traversed questions of the broader Swahili poetic worlds and their roles in this world of political imagination and historical memory, poetics more broadly as a historical relation, the particularity of Muyaka as figure and poet, poetic archives and matters of sources, and the (perhaps political) reactivation of Muyaka’s poetry and histories within these archives.