When Rain Clouds Gather: A Quest to (Re)Imagine muted Black Women’s Artistic and Intellectual Legacies Anew

Sandile Ngidi and Sanele Ntshingana report on their engagement with the exhibition

In 2001, African literature and feminist scholar, Phumla Gqola observed that “there are various Black women’s intellectual legacies in South Africa, and they are not self-evident”. She argued that this “is due to a variety of racialised and gendered processes that mask, mythologise, and delegitimise women’s agency” relegating them to “stereotypical, stoic, mother roles, hypersexualized, passive and supportive roles”.[1] It is no accident that 21 years later, two Black feminist curators of a younger generation, Portia Malatjie and Nontobeko Ntombela, made this lack of self-evidence visible; or as the literary historian Athambile Masola would say, to make visible ukungabonwa kweheritage yamakhosikazi. [2]The two curators stage the versatility and the presence of yet muted Black Women’s artistic work from South Africa produced between 1940-2000. What is public life after-all if those who shape it and reshape it cease to be part of its cultural and intellectual imaginary?

When Rain Clouds Gather: Black South African Women artists, 1940-2000, is a cross-generational meditation on Black womanhood in South Africa. It is thunderous, and is aptly titled gesturing to the novel of the same name, by the banned and exiled South African Bessie Head, published 53 years ago. Like the novel’s setting in the 1960s, and Head’s Pan-Africanist commitments, the exhibition is both a site where hues of darkness and delightful splashes of bright colours shed light on the ontological crisis of the largely untenable material conditions of Black women during apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa.

A group of six Archive and Public Culture students and associates along with History of Art students from Michaelis School of Art (UCT) and third-year Art History students from Wits University participated in a walk-about organised by the two curators of the exhibition, Nontobeko and Portia, at the Norval Foundation. Here the group engaged with 120 artworks of 40 Black Women artists from South Africa. The Norval Foundation is located in the Steenberg area of Cape Town. It is a potentially alienating space, given its exclusive demeanour, and the fact that it abuts Table Mountain National Park, far from the world, and the very people who inspired the art that breathes life into this historic exhibition.

The ambitious project critiques South Africa’s recent and not so recent pasts in a series of visual and semiotic texts by leading Black South African women visual artists from different age groups, social and political strata, and all walks of life imaginable. The hour long meticulously and patiently guided tour included high-end theoretical articulations of artistic practice and bold Black Consciousness-centred feminist perspectives which see Black women rage against land dispossession, the totalising brutality of apartheid, whiteness, patriarchy, and the choking reality of being a Black woman in the world.

The methodological and the theoretical approach of this exhibition is fresh, offering new ways in which to engage this large body of artwork. The exhibition poses questions rather than giving definitive answers. It highlights moments of silence and absences in the archive. The curators do not position themselves as expert on every question; rather they present the archive of this work as a place for ongoing engagement. This exhibition thus acknowledges the “porous nature of the archive” and that is it only when one moves from the place of not knowing, to a place of curiosity, of questioning, of having conversations, that one is able to deal substantially with the complexities of archive. This conceptual and methodological framework invites the public to critique the exhibition and even to add further art or contextual material. Indeed the exhibition keeps on being expanded and this captures the dynamic nature of the archive.‘

The exhibition brings together forms and practices - painting, printing, photography, pottery, and sculpture - that do not always find themselves in one space, putting the artists in conservation with one another. Making such a body of work visible in one space evokes making rain clouds gather.

While the exhibition is organized in terms carefully conceptualised themes, such as the political, love|pleasure|intimacy, land|landlessness and landscapes, spiritual and religious conjurings, speculative/spectacular and wrestling traumas, many works easily fit into multiple themes. It is not the curators’ intention to lock these works in one theme. For example, the artist unknown (Bongi Dhlomo)’s work At the end of the day(1992) is placed in the political room. It is an acrylic painting of a headrest a homage to the artists who are not known and left unremembered. The artist unknown (Bongi Dhlomo) puts her name in the brackets as an artistic stance to highlight the erasure that is facilitated by nexus of collecting the work and writing it into books. This inscription is both a methodological and conceptual intervention. The artistic stance has reportedly often been overridden by curators who are oblivious to the politics of ascription and who put Dhlomo’s name first. This work could as easily fit in the trauma-themed room.

Artist Unknown (Bongi Dhlomo), picture taken by Sanele kaNtshingana.

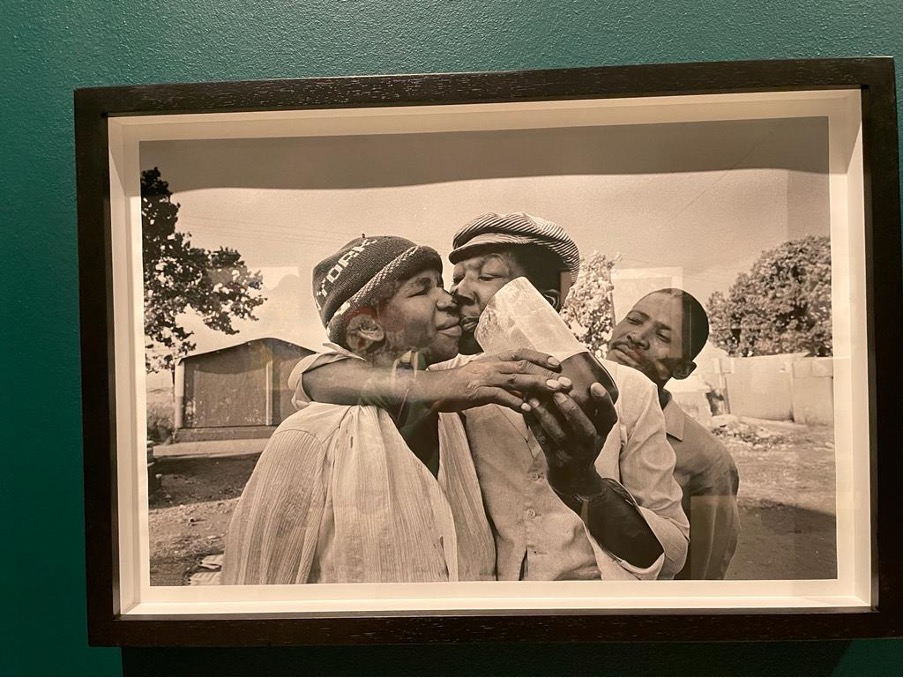

Ruth Motau’s Shebeen series of photographs shift our imagination of the shebeen space as a ‘death’ zone into thinking about it as a political space that was the heart of political imagination, a space for pleasure, of counter-hegemony, and of resistance. This evokes Lewis Nkosi’s concept of Tsotsi intellectuals in Sophiatown in the 1980’s who used shebeens as generative spaces for Black people in imagining and setting direction of their own lives and political order. The love and pleasure room seeks to transgress what Phumla Gqola observed in 2001 as women in intellectual and public imaginary being relegated to “stereotypical, stoic, mother roles, hypersexualized, passive and supportive roles”. This room thus invites the audience to think of Black women’s bodies in a state of leisure and rest, in celebratory mood and as happy, luxuriating in pleasure and the nice things in life.

Image of photo in the Love and Pleasure room in the exhibition. Photo courtesy of Sanele kaNtshingana

The exhibition is in the company of other intellectual and public interventions that seek to breathe life into a new imaginary of Black souls, ways that seek to ukuzihlambulula from the colonial quagmire. The issue of language - not only of writing but of theorisation, the question of who commissions the work and how that shapes it, and the space in which these conversations take place - are all difficult and important, if not unavoidable questions. It cannot be expected for one person to attend to all these issues; however, the acknowledgment of these theoretical traps is necessary.

Commenting on the decision to have the exhibition at the Norval, Portia noted: “We are obviously very critical of these institutions. It’s also very important not to take away our agency in this. We have pushed and pushed and pushed at every turn. We pushed for this exhibition to happen. We pushed for this exhibition to happen in a particular kind of way. We wanted this exhibition not to be in just one or two spaces, or in that space, but said it deserved a certain kind of magnitude. Inasmuch as it matters who is commissioning, we also have the agency, and have had the voice to always push back, and say no, and say yes, and say no, and say yes. If things don’t go the way we believe they should, in terms of the integrity of the project, we also have the power to just pull out, and say, no. If this can’t happen in the way that it needs to happen, then it mustn’t happen at all. We can’t take away the agency we have in putting this together. But also acknowledging that if this was happening in a different space, that might have been less fights, less push backs that we encountered.”

Nontobeko added: “This has always been a crisis around particular practices of artists whose work is produced in a different language and must be Englishified in this space. How do you transport that experience into an English space, an English space that is expecting you to explain, translate and represent the work in a particular way? That has often been violent in most of the cases towards the work. You never really get to understand it. You won’t be able to really understand it from an English perspective, that is so limiting in unpacking certain works.”

When rain clouds gather is a timely necessary exhibition that encourages the public to think seriously about Black women’s roles in art historical discourses.

[1] P. Gqola, ” Unconquered and insubordinate: Black women’s intellectual activist legacies” in Becoming worthy ancestors (Xolela Mangcu).(Wits University Press, 2004),. 67-88

[2] See Ukuzilanda and The Photographic Image:A Meditation on the Visual Practices of Lebohang Kganye and Alice Mann (http://www.boxesart.com/en/exhibition/article/51)