Posted on January 19, 2011

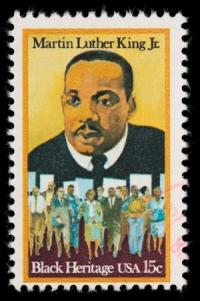

King was an ordained Baptist minister, whose moving speech and inspired leadership helped steer ahead the efforts of the civil rights movement. His contribution to the struggle for racial justice in the U.S. is undeniable and indeed beyond words.

Yet, getting King recognized as a legitimate figure in the making of contemporary American society has been an endless battle. Attempts to get a federal holiday in King's honor began soon after his death in 1968. But it was not until Ronald Reagan's administration that the holiday was eventually passed into law, almost two decades later.

Such resistance did MLK Day receive that some states chose to give it alternative names, like 'Human Rights Day', 'Civil Rights Day', etc.

Perhaps the most violent of disavowals of King's legacy came from ultra-conservatives, who went to the extent of combining it with other holidays; take Virginia state for example. The holiday was named 'Lee-Jackson-King Day', and celebrated the lives of Confederate Army generals such as Robert E. Lee, alongside Martin Luther King.

The co-celebration of such disparate legacies is an insult!

Inaugarating King's legacy in this way instantly locates him ambiguously within American public imagination. While claiming to place MLK's name into the history books, it conceals his contribution by placing it alongisde the contributions made by Confederate generals.

However, for those who had been rooting for the recognition of King, even this may represent a small victory.

The truth is Black voices have been severely compromised in the status they are given in public memory.

Consider the status given to Enoch Sontonga's hymn 'Nkosi Sikelela iAfrika' in South African public life. Sontonga's hymn was a driving feature in the struggle for liberation, not only in South Africa, but in other parts of the continent too. Following liberation, the hymn was adopted by several countries in southern Africa as their national anthem. In so doing, linking the different territories in their shared history of white oppression.

South Africa, on the other hand, devised an arrangement which combined Sontonga's hymn with the Afrikaaner nationalist of tune 'Die Stem' in its national anthem; thereby giving equal weight and significance to both hymns. Given the opposing histories, the co-existence of the two in one national anthem seems bizarre.

But I believe the conflation of the two hymns into one body, captures precisely the difficulties of negotiating black interest, experienced by those who were in leadership at the time. They chose to prioritize peace-building over naming-and-shaming, at the expense of the full recognition of Sontonga and the vision he strove for in his hymn.

Heritage plays a powerful role in the public imagination. It is restorative in its performance, reconciling that which history can never undo. It allows those who were victims to make peace with past violence and displacement experienced through colonial exploitation. But it seems that even in this imaginative realm, those who were violated are unable to get the acknowledgement that is due to them.

Black activism, across the world, has produced results. But these gains have been constrained by the institutions, legislations and practices that compose them—which remain deeply entangled with white domination. The response of these institutions has been defensive at times and half-hearted in instances where apologies have been made.

The struggle to get Martin Luther King recognized in the United State is reflective of a much wider struggle for black recognition across the world.

In this regard, Martin Luther King famous words: 'It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that's pretty important,'(www.quotationspage.com) can be viewed as a prophetic realization of this struggle. In a sense, he was already aware of the constraints that were to hinder the proliferation of his own legacy.

Only in the year 2000 did the holiday become officially observed across all 50 states, and is still a point of much debate till this day.

Thokozani Mhlambi lectures in the Department of Music at UNISA and is an Archival Platform correspondent.