Posted on March 12, 2013

It is the month of love. Red and white roses, wine, hearts, chocolates and letters are markers of the 14th February. Some people are arguably more romantic as they often extend Valentine’s celebrations to the last day of the month. Gestures and symbols of love are more often than not considered personal; that is exclusively for the eyes and ears of those associated in a particular form of a relationship. However, what happens when letters of a romantic nature and other symbols of love enter an archive? Most importantly, what qualify as 'personal information', who and what determine its level of access?

For this piece, I searched the University of the Witwatersrand, Historical Papers research archive. The latter was found in 1966. It is storage for at least 3300 collections which date as far back as the 17th century. The Wits Historical Papers archive shares with researchers a varied range of political, historical, social and cultural collections which are open to the public and some with restricted access. Encouraged by the month of love, I requested for a collection that may perhaps share with readers the kinds of correspondence that take place between people who are in a form of relation, particularly romantically involved. The intent for this issue was to explore how such letters are kept, who accesses them and what can they tell the reader about the past and (in some cases) their ancestors. One of the staff members referred me to Rusty Bernstein's collection.

Lionel 'Rusty' Bernstein was born in Durban 1920. He was the youngest of four children of the Bernsteins, who were European emigrants. Orphaned at age 8, he was sent to finish his education at Hilton College. After completing his matric he moved to Johannesburg to work at an architect's office. In 1937, he joined the Labour League of Youth (LLY) and the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). While he was volunteering for the South African Army in 1941, he married Hilda, whom he met during his time in the LLY. Rusty left the army in 1946 to reunite with his wife Hilda and their four children. The reunion was short-lived, as he was also arrested in 1956 for treason. His trial lasted for more than 4 years before he and the 155 charged men and women, were found not guilty. Throughout this period, he and his beloved wife had maintained close contact through letters that can be found in Bernstein's collection at Wits, though some have limited access.

His wife, Hilda Bernstein, was born in London in 1915 to Simeon and Dora Schwarz. Her father was a Bolshevik who became the Russian Trade Attache' in London in 1919. He left the family when he was recalled to Russia. Hilda left London for South Africa in 1933. Subsequently, she joined the youth branch of the Labour Party. By 1940, she was also a member of the CPSA, in which she served on both the district committee and National Executive. Hilda Schwarz was one of the founders of the Federation of South Africa Women (FEDSAW) and was also instrumental in the organisation of the anti-pass women's march in 1956.

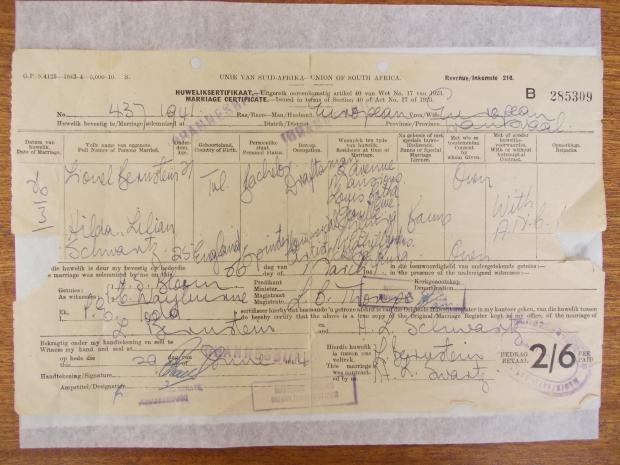

Both Rusty and Hilda were lifelong members of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and devoted their lives to the formation of political movements and organisations in South Africa. Their marriage license lay in the collection donated by their daughter, Toni Strasburg. This symbol of Rusty and Hilda's union is not restricted for access, although some of the complementary letters which the couple wrote to each other have restricted access. When asked about powers to determine access, Wits' archive staff maintained that donors often stipulate the sections of the collection that needs restricted access. In the case of Rusty and Hilda Bernstein's collection, it was their daughter Toni who made the stipulations.

A marriage license is symbolic of a union. However, this cannot be said for all forms of marriages, for Customary law gives recognition to traditional marriages whose significance is not tied to a legally binding document such as a marriage licence. The latter were unheard of prior to the Middle Ages. Marriages were private contracts between two families that may or may not have the consent of those being wed. Marriage was not only for reproduction, but for also building financial, social and, in some cases, political alliances. When the state-run Church of England decided it wanted to have a say in approving marriage partnerships, laws regarding marriage licensing were established to ensure a level of control and source for revenues. It can also be argued that states' increased control over marriages was primarily to prohibit interracial marriages. This perhaps stages the need to interrogate the history and significance of marriage licenses across societies.

Although generalisations cannot be made, marriage licenses can, among other things, be revealing of family histories and genealogies. Their dates of issue are telling of the social context. The past and memory can be constructed from a close reading of such a legal document. In the absence of this legal document, I asked the question: what are other symbolic objects that can trigger memory with regards to a union of two people, particular in those marriages recognised by customary law. Mr Khumalo recalled that, 'a kist, blankets, dishes, and other wedding gifts were triggers of memory as they formed a symbolic part of marriage union.' Such tangible objects are significant for they remain symbolic and constitute a remembrance of a union of two people even when they are dead.

The incessant thread coming out of this piece is the question of what documents are considered personal and which qualify to be accessed without any form of restriction in an archive. A marriage license is a personal and significant legal document declaring a change of the marital status of those involved. It can be used to trace ancestors, a history, culture and an identity. So what happens when a personal document enters a space of public significance such as an archive? What are the terms and regulations of handling such documents? In this case Bernstein's daughter, Toni, whose parents were well known political figures only gave limited access to her mother's diary and a few letters. These are letters which can be accessed with special permission from the donor. Here, the archive seems to be a mediator between a donor and researchers. Arguably, the donor, be it an individual or an organisation appears to be of influence as they can grant or deny a request for certain documents. This raises the question as to who owns knowledge presiding in the archives for the release of certain information without the consent of donors can lead to violation of an agreement entered into with the university? More research needs to focus particularly on archive donors, their intentions and the politics of donating collections, an understanding of which may explain why certain personal documents have restricted access while others are open to the public.

Reference

Church of England Archdeaconry of Suffo. (2012). 'Marriage Licenses from the Official Note Books of the Archdeaconry of Suffolk Deposited at the Ipswich Probate Court 1613-1674', Nabu Press

University of the Witwatersrand, Historical Papers. A3299 BERNSTEIN, Hilda and Rusty, Papers, 1931-2006