Posted on November 15, 2011

The ringing of church bells on a Sunday morning always reminds me of my upbringing in a Catholic home. My parents were pious, so I attended a Catholic Church and school in Parow.

Not responding to the church bell inevitably leads to guilt. Come rain or shine, South Africans, Muslim or Christian respect its powerful religious reverberations. Like the church bell beckon Christians to church, the Bilal serves as a spiritual echo to all Muslims to come to mosque and pray.

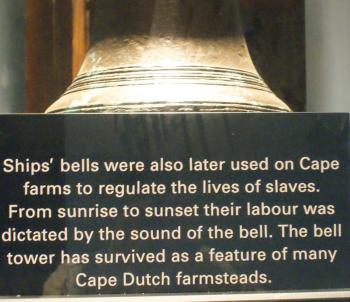

During the period of slavery at the Cape, from the mid-1600s through to the late 1800s, this legal bell code was not only bound to religion but served as a signal for slaves at the Cape to start work. From sun up to sun down slaves heeded to the master's call.

On the wine-producing farms especially, this call announced slaves' 'Communion of Labour', or their 'Dop' of wine given to them at each ring of the bell. Its fearful echo across the huge wine estates of the Drakenstein area, Stellenbosch, Paarl, Wellington, Franschhoek and other areas must have been a constant reminder to slaves that the law is waiting.

This system divided the day into 'dop', work, work, 'dop' 'dop', work and more 'dop'. While the church bell called the landowners and their families to church, the Cape Farm Bell Tower called the people of colour to work. The Cape farms had some of the worst labour practices and among these was the 'Dop' system (tot system) where workers were paid or part-paid in alcohol rations.

The arrival of a white-only representative government and Cape legislature in the late 1800s provided the super glue to continue the daily 'dop'. It made sure that farm workers remained drunk and unstable. This government prescribed harsher penalties on farm workers for transgressions, especially absenteeism, breach of contract, and desertion - this curbed their movement in search of higher wages. The fact is, it perpetuated alcohol dependency while imposing a range of criminally punishable work offences. Other means of control were instituted like indebtedness through advancing wages.

The Master Servants Act of 1856 served to extend white rule and made the emancipation of slaves in 1834-1838 a non-event. Similarly black and coloured people still suffer under our newfound Constitution.

Like the English negotiated worker rights with white Afrikaaner landowners, so the African National Congress shook hands with Nationalist and rich, white business in 1994. The burden of democracy hangs heavily on the backs of impoverished rural farm workers and urban factory workers. In the end democracy continues to advance white interest, not withstanding BEE gluttony. To most poor people, democracy remains unattainable.a

And although the payment of alcohol to farm workers as part of their Basic Conditions of Service is no longer legal in South Africa, sadly alcohol addiction remains one of the major socio-economic, physical and psychological challenges facing farm workers, families and friends today. Most of our families on the Cape Flats, for example, have felt the chaos that surrounds alcohol abuse. Sadly we have inherited the 'Dop' System. Frequently we need to get drunk in order to survive the minutes and hours of the day, and tomorrow is yet another day. We try everything to get hold of it, we steal, beg, borrow, lie, we will even bargain our bodies for that cocktail of despair. Farmers profit with payment and hectares and hectares of land, and 'dop', work, work 'dop', 'dop', work continues.

The Cape's economy was tied to world markets and was capable of generating sufficient capital to sustain the culture of a ruling class. This bourgeois assault on slaves and the Khoe maintained an impoverished alcohol-addicted and landless 19th, 20th century Cape working class society.

Most farms are steeped in Khoe and slave histories. The truth is the Gorachouqua Khoe lived in the territory of Franschhoek, Paarl and environs with the main Khoe kraal based at Klapmatsburg. Small groups of pastoralists had nomadic residences stretching to the edges of Stellenbosch, Franschhoek and Wellington. Both the Khoe pastoralists and the San hunter-gathers hunted game in the area. This was all to change quite dramatically from 1679 in Stellenbosch, 1687 in Paarl and 1692 in Franschhoek. Boschendal, Vergelen, Meerlust, Solms-Delta, Spier, Elsenburg, Groot Constantia, and many others were appropriated with brute force. Mostly it was acquired through theft by corrupt officials of the state and the invasion of Khoe and San territories.

It is no secret that this landed class was built on the backs of slave and Khoe hard labour. As profits accumulated, a class of rich white farmers emerged; indeed the production of wine nearly doubled between 1808 and 1824. For the San people genocide attacks were carried out by Dutch-led commandos throughout the 1700s.

Remembering slavery at the Cape has shown that by 1827 the Stellenbosch district, which then included the entire Drakenstein, saw rapid growth. Profits soared in wine production and the farming of wheat, rye, barley and livestock. This saw a remarkable improvement in the Cape's economy. The population of slaves were 8 455 in relation to the total population of 16 325, of which 30% was our Khoe and San, huge labour force at the disposal of landowners at any time.

Later statements made by racist tyrant Adam Tas, mouthpiece for apartheid's ideology and white Afrikaans Nationalism led to the forced removals of coloured and black people. These ethnic cleansing manoeuvres ensured white-only towns in Franschhoek and other Drakenstein towns some 250 years later. It is said that Adam Tas insisted slaves work on a Sunday and Christmas Day.

A 2008 Human Science Research Council (HSRC) household survey, 'Sober N Clean, Alcohol still the curse of the Cape', revealed shocking statistics. It said that 'Coloureds' had higher levels of drinking in their communities. Eighteen percent of 'Coloureds' abuse alcohol, compared to 11% of black people, 7% of whites and 1% of Indians. Drunkenness was responsible for 59% of violent deaths in the Western Cape, compared to 47% of violent deaths in Durban and Johannesburg, and 51% in Pretoria. Cape Town has the highest number of alcohol-related road deaths, a staggering 59% of alcohol related road accidents; compared to 47% in both Durban and Pretoria. The Western Cape has one of the highest rates of foetal alcohol syndrome in the world.

Alcohol's association with crime, violence, risky sexual behaviour, trauma, and child abuse, high rates of TB, HIV, child and adult malnutrition, violence against women, job losses and family dysfunction is startling. The truth is that we are addicted, the consequence of a problem mostly left untreated.

After emancipation during 1834-1838, many freed slaves settled in Pniel and Herte Street in Stellenbosch, Dirkie Uys and other streets in Franschhoek, and in Berg, Ou Tuin and School streets in Paarl, and in the heart of Wellington.

Today, tourists sip their fine wine as the descendants of slaves continue their work beneath the burning Cape sun. For the rich farmer it was a fringe benefit that kept social order, for workers, back-breaking toil under the influence of wine. So the Slave Bell Tower continues to resonate, 'dop', work, work, 'dop' work across the rich farm estates of the Western Cape.

Let the 'yards' on the Cape Flats, Hanover Park, Langa, Bonteheuvel, Mitchell's Plain, Gugulethu, Fractreton, Khayelitsha, Blikkiesdorp, etc serve as a reminder of the 'Dop' system's control over our daily lives. The incorporation into the British Empire at the beginning of the 20th century brought fruits that were bittersweet. There would be no freedom for as long as their former owners and masters stayed on the land.