Posted on June 22, 2011

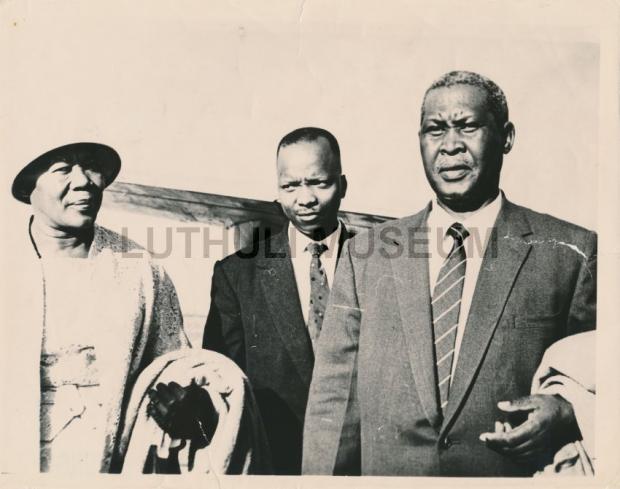

Nokukhanya Luthuli, M B Yengwa and Chief Albert Luthuli en route to Oslo, Norway to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for 1960 (1961) LutMus2005.01.179 Yengwa Collection, Luthuli Museum

As museums go, the Luthuli Museum is a very new institution. Opened in 2004 as a national legacy project, the Museum's mission is to conserve, uphold, promote and propagate the life, values, philosophies and legacy of the late Chief Albert Luthuli. These national legacy projects are a Government initiative to establish commemorative symbols of South Africa's history and celebrate its heritage. They comprise, amongst others, the Sarah Bartmann Centre of Remembrance and Freedom Park Project, as well as Chief Albert Luthuli's House.

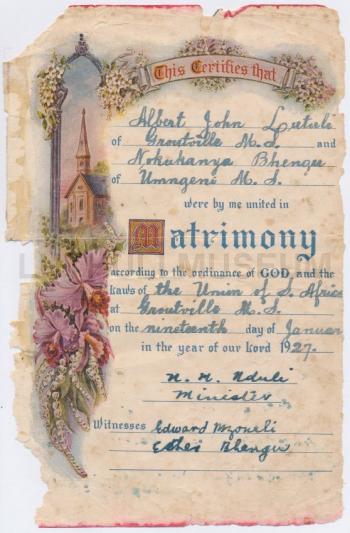

Luthuli's outstanding achievements, which include being Africa's first Nobel Peace Laureate, are barely perceptible by his humble home in Groutville, just outside Stanger on the North Coast of KwaZulu-Natal. This is where he spent most of his life as President of the ANC under house arrest, according to the terms of the Apartheid Government's banning orders.

Our decision to digitally catalogue and digitise these collections was prompted, in part, by the Department of Arts and Culture's (DAC) wider interest in digitising South Africa's national heritage assets. As the DAC emphasises, the knowledge preservation aspect of digitisation is enormous: if the archival storeroom floods or is set alight, the knowledge captured within our artefacts will still be available in some way through digital surrogates. From an access point of view, we want to share our archival documents and artefacts relating to Luthuli and the Liberation Movement with even more people than are able to travel frequently to Groutville. One feasible solution that we came up with was making our digital collections accessible through an online catalogue on our website. Our concern, however, was how we could reconcile a wish to make these valuable artefacts widely accessible to all interested parties without compromising the Museum's commitment to safeguard the integrity of its collections.

Such ideas set our minds spinning. A point in favour for the Luthuli Museum is that it's digitisation project is not foreign funded; we have the opportunity ourselves to select which materials we digitise and so avoid servicing a purely global Northern agenda. Being formed in the post-apartheid period, the Museum collections are not overtly influenced and burdened by a colonial discourse as other older museums in South Africa are. However, it would be naive to presume that our collection is either apolitical or immune to these influences. While not directly constructed under the conditions of colonialism and apartheid, what survived this era to be preserved by the Luthuli Museum is undeniably affected by these historical conditions. Certainly, although we continue with our best efforts to collect oral histories and alternative narratives, the current silences in our archive ring as loud as the cacophony of voices within it for these are the stories that the previous regime destroyed and quashed out of existence. And then the issue of who can retrieve our digital collections online persists, since low fixed internet access levels in South Africa mean there is a real risk that only people in the global North who enjoy high speed, low cost internet will be able to use this resource meaningfully.

We fully acknowledge that the Luthuli Museum digitisation project will be a learning curve. Our best hope of success is to engage with other heritage institutions participating in digitisation projects so that we can share knowledge and experience and, hopefully, produce a resource that will indeed assist us with our vision to 'let the spirit of Luthuli speak to all.'

1) Premesh Lalu, 'The Virtual Stampede for Africa: Digitisation, Postcoloniality and Archives of the Liberation Struggles in Southern Africa,' Innovation 34 (2007): 28-44.

2) Michele Pickover, 'Contestations, ownership, access and ideology: policy development challenges for the digitization of African heritage and liberation archives' (paper presented at the First International Conference on African Digital Libraries and Archives (ICADLA-1), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, July 1-3, 2009).

Laura Gibson currently manages the digitisation and collections management project at Luthuli Museum, Groutville, KwaZulu-Natal. For more information about the project, you are welcome to contact her: email: laurakategibson@gmail.com / phone: +27 32 559 6822