Posted on December 13, 2011

A few more stragglers wander in and take their seats. Programmes are handed out and I sit down to read. 177 years ago, on the 1 December, 1834, the Cape erupted in song, dance and the sound of gunpowder. It was the official end of slavery and those who had been freed were celebrating their newly given freedom. Today, it seems, the celebrations are an act against forgetting and one of rumination, of consciously thinking through the effects of emancipation.

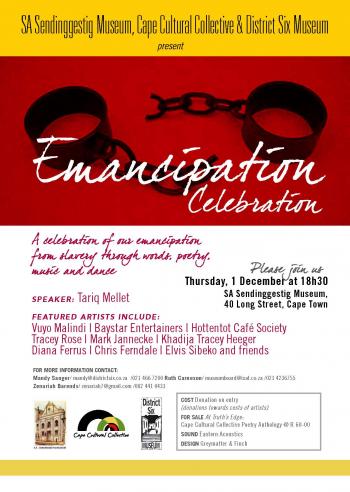

A woman, grey of hair, rocks a crying toddler on her lap as Mark Jannecke, the first performer of the evening, takes the stage. As he is hunched over his guitar I read the programme describing him as "using music and writing therapy as interventions for initiating the healing process within the individual". His gentle strumming takes on acoustic furiousness at times but slows again. He is followed by the Baystar entertainers, a brass band marching into the church playing "Oh When The Saints Come Marching In". I spot a five-year-old band member playing the drums and smile. The church is now relatively full and the band plays its final number. The keynote speaker, Tariq Mellet, takes the stage and, finally, the historical significance of what we are celebrating hits me in the face.

In the first few lines of his address, Mellet describes how he used to watch one of the nuns at the convent where he grew up bend her knees and pray before a statue of Peruvian Saint, Martin de Porres. Witnessing a white German nun's devotion to a black saint was something he described as fascinating. He talks about how slaves in the Cape were as young as five years old. He repeats how Creolised his identity is as a result of his ancestors who were from different countries and ethnicities. He refers to an intergenerational historic trauma that he and many others in this country suffer, a trauma related to the suppression and distortion of slave history; the existence of this trauma means that the city holds a lot of pain, he says in conclusion.

Mellet's speech is followed by a performance from the Hottentot Café Society, a duo comprising Jethro Louw and a man who refers to himself as "Colin the Bushman". Their work is a blend of music and social commentary. Their commentary is slightly conventional, Jethro raps about blood debts and how politics isn't bread.

After their short performance, an impromptu speaker gets worked into the programme. He describes himself as representative of the Khoi nation and delivers a speech about inherited helplessness. He describes the marginalisation, and, at times, the distortion of Khoi history and he then addresses the audience and tells us to shake off the inherited helpless inflicted upon us by our brutalised history. The consciousness I referred to at the very beginning of this piece as being one of the central themes of this celebration, enters the room, briefly. He has a point, I think to myself, and even though I will him to explain this idea of inherited helplessness, he finishes and takes his seat in the pew not far from mine.

Tracey Rose leads the congregation in an acoustic rendition of Bob Marley's "Redemption Song" followed by Diana Feruss reading a short story from her collection. The Masifundisane educational dance project presents a three-man piece titled "Why-How-Where and When?" It's a contemporary dance piece that speaks of bondage and freedom, with Wendy appearing carrying a heavy load on her head that is shed during the dance. Khadija Tracey Heeger delivers a poem followed by Chris Ferndale. The poetry is a hard-hitting mix of words involving images of oppression and freedom. It is important that these voices be heard, I just find myself wishing that it was more thoughtful, more conscious in the way described very briefly by our speaker who referred to the inherited helplessness.

Overall, the celebration was a necessary act of remembering the history of the Cape, one that demanded we rethink what the freedom celebrated by those in 1834 means for us in the context in which we find ourselves now. The artists, speakers and audience who took part in this event understood this celebration as one of looking back into the past but also of looking to the present and to the future in unearthing, rethinking and possibly reworking the identities we now hold.

Busi Mnguni is an Honours student in the Department of English at the University of Cape Town.