Posted on June 2, 2014

Maart also says that 'The apartheid archive can be seen as a white male archive'. Looking at these archives now is to be able to read what was glossed over, to introduce the black experience, the female experience.' What Maart is suggesting, of course, is that the archive is always larger than any official history, especially where the record has been sanitised; and that the archive is never static but always open to new records and understandings of the past.

Interestingly, Maart's curatorial focus on art and the apartheid archive elicited an irate response from one Nic Batt: 'There is an entire industry in South Africa of people dependent on the apartheid legacy which means people like Maart are in for the long haul. They are effectively never going to embrace a post-apartheid South Africa, always using the past as their foundation for definition. They effectively keep apartheid alive and well.'

Batt's remark is based on the erroneous notion that there is a dividing line called '1994' that neatly, and in one fell swoop, separates the colonial and apartheid pasts on the one side, and the post-apartheid era on the other - the idea that the apartheid legacy does not infest the present. Contrary to Batt's view, to embrace post-apartheid South Africa, is to deal with the apartheid legacy. Batt also dismisses the work of the entire memory industry in South Africa, which centres on a preoccupation with the archive, not least by some artists. But while some artists work with the records of the past - these are usually upfront accounts of life under apartheid - as a strategy, art itself, however, constitutes an archive as it represents a record of human engagements with the world and the self, and our aesthetic drives.

As historical and contemporary art presents evidence of human dynamics - art is a sort of extensive, near-immeasurable, multi-faceted and complex record there of - it is a particular manifestation and sub-set of the human trace, the entire record of our cultural, social, political, spiritual, scientific and intellectual endeavours. Here the archive is everything said - either documented or passed on orally - written, performed or rendered visually, making it a vast information system about human experiences in both the past and present. This leads to the idea that the archive is in fact a metaphor, or concept, relating to always contested knowledge about what we have done, produced and represented in the past over a vast expanse of time.

This way of looking at the archive is, of course, quite different from the conventional view that the archive is a physical place, established for the conservation, governance and accessioning (ordering) of historical records considered important for a nation or community. This view has been considerably damaged by relatively new understandings of the meaning of archive. For one thing, the term no longer refers to only physical places to which we need to go to engage the material traces of human existence; nor does it necessarily refer to traces that are tangible. A much discussed case in point here is electronic textual and visual records stored on computers, or on the Internet, which, of course, completely confounds the idea of the archived document or object as an original resource.

Another instance of the immateriality of the archive is stories told orally, and which, in some cases, are passed on from generation to generation, as we have in the African tradition. This makes each one of us an archive in a sense, for, as keepers of knowledge and memories, and subjects of experiences, we all have stories to tell, only a minute fraction of which is captured, or recorded. Not for nothing did an Archival Platform correspondent write that his grandmother is an archive. Each one of us is also an archive in quite another sense as our DNA is a storehouse of archived (genetic) information. Here we have archives that not only eschew the idea of the archive as a physical place, but that exist outside of human agency. And that really sets the cat among the pigeons!

But no matter whether we understand the archive as any storehouse of organised human information, or more broadly as all manifestations of the human record that as a whole constitute our collective memory - the sum total of the human trace across time and cultures - art objects are undisputedly in, and of, the archive and vital to the meaning of the term. The distinguishing feature of these objects is that they are all works of contemplation and visual constructions of the human imagination in various idioms and styles that express the ideologies, aspirations, concerns and subjectivities of humans across cultures and eras. They stand alongside other forms of the human trace, such as letters, books, oral testimonies, sound recordings, particularly in respect of music, films, photographs, personal memorabilia, posters, badges and political banners, and are no more or less significant for understanding the meaning and scope of the archive and memory.

Selections from the aesthetic trace, the body of works we label as art, are located in collections - archives by another name. These are organised formal repositories belonging to, and under the custodianship of, individuals (private collections) and institutions (public collections), such as corporations, universities, and municipal, provincial and state museums. It is the art museum as archive that is of particular interest here, the idea of which first emerged in South Africa in the late 19th century as a colonial implant from Europe. The only difference between the art museum and other types of archives, say those housing books, as you have with a library, is that it is a public repository for particular manifestations and versions of the human trace - visual objects made in accordance with various cultural scripts or agendas, or in opposition to these, as is the case with avant-garde art and other forms of counter-culture visual expression.

Art museums, of course, are never places of neutrality as they are always instruments and transmitters of cultural power, authority, and ideology. They not only legitimise and sanction some artists and not others, but also certain modes and categories of artistic practice - and all in the name of 'excellence', a particularly contentious and contested notion as it raises the question of whose standards and values are being applied. This means that art museums are inevitably biased and tainted by prejudice as, because they glorify and elevate only some artists and modes of artistic production, their collections are always marked by omissions. Like all archives, museums are about conservation and memory, but also about the selection and exclusion of aspects of the record, or what has been produced: they exercise power.

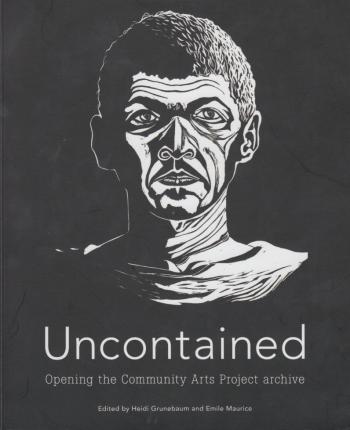

South African art museums, like Iziko South African National Gallery, or the Johannesburg Art Gallery, are classic cases of institutional power. Their histories are distinctly marked by their complicity in the erasure of cultural memory because they legitimised and racialised the South African art canon through excluding works from the black art archive until the transformation imperative of the early 1990s. Connected to this is another issue. As legitimising agencies and arbiters of taste and what is acceptable and of value, art museums excised from the official record of South African art anything that was made outside the academy and beyond the tastes and interests of the ruling class and their apartheid-minded curators. Accordingly, excluded from museum collections were works perceived to be 'low art' - visual representations considered to be mundane, without aesthetic resonance and of a populist order, such as those made by community artists. Also excluded were works not made in the Western tradition of fine art, particularly here cultural objects representing traditional populations - what may best, and most appropriately, be described as classical African art.

Since the late 1980s, when institutions, including museums, and historians first embarked on memory projects to recover lost histories - this was the start of what has become South Africa's memory industry - much has been done to address the representational injustice of the past through restitution projects. Today art museums are far more egalitarian and representative of race, gender, class, cultures and generally the plurality of artistic production in South Africa, so reflecting a multi-vocalism and broadening of the art canon. What we in effect have today in respect of the art archive is a new official cultural record that suits and supports the post-1994 agenda, which espouses diversity, multi-culturalism, representivity, inclusivity and a shared heritage as cultural foundations and foci for reconstructing the nation.

But while what was once marginal in South Africa's official art record is no longer so to a large extent, the margins to mainstream story - the country's project of cultural restitution - remains incomplete. This is not because curators and art historians lack political will to continuously refigure the art archive by addressing gaps and omissions. Rather, it is because art museums, as with other kinds of museums, are hampered by severe constraints, human and financial resources in particular. Gaps, omissions and silences will persist, and as such, art museum collections, or archives, will always be open to contestation. We should therefore always treat them with suspicion and mistrust.

Emile Maurice is an Archival Platform correspondent. He is also a resident fellow at the Centre for Humanities Research, University of the Western Cape.