Posted on May 11, 2010

Music Heritage has never been properly documented in South Africa. Public institutions, such as Museums, continue to grapple with issues around gaps, representation and inclusivity within their spaces. The history of black music continues to be under-represented.

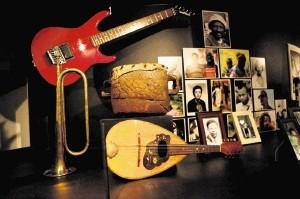

These are the reasons why Noni Ntaka (an arts journalist and filmmaker) decided to partner with the Museum of Cultural History in Pretoria in the production of Isizwe Music Exhibition. The exhibition (scheduled to begin in May 2010) sought to showcase various musical instruments, book, magazines, tapes, records, CDs and clothes that characterize the past eras. In addition to this, the exhibition hoped to include replicas of visual arts and costumes characterizing the different periods.

After hearing about the exhibition through the media, I decided to make an appointment with Noni Ntaka in order to find out about the project, and to fill the rest of those in the Archival Platform network, who reside outside Gauteng on what's it about.

When I gave her a call to ask for us to meet she told me that the exhibition had been cancelled due to funding hiccups. Her voice on the phone sounded sad and yet very assured. It seemed, even with the hiccups, she was ready to go on. I wondered: where does the woman get such strong will?

But it was when she told me that she has been working on this project since 1995 that I became convinced that this was her life work. Noni's interest in the area of archiving music is a heartfelt one. She is the daughter of Blues Ntaka, a South African jazz musician who was exiled in Switzerland and died in 2001. She began to question herself about the visibility of great South African musicians, like her father, whose lives had never been documented.

Noni remembers as a young girl being taken by her mother to a museum. When she discovered it was a bird museum she refused to go in, to her mother's dismay. She says 'It was unfair that children in South Africa are not given the opportunity to see historical instruments, instead they are taken to the museum to see birds and animals.'Â

She became further concerned by the fact that where those instrument archives do exist they are often kept in universitie - spaces which are out of reach for the majority of people. "Music is not only for the elite,"Â she insists. "What about those musicians who are self-made? They have not gone to university but have learnt for themselves how to play and sing."Â

Following the press release about the exhibition, Noni says she has had an overwhelming response from ordinary citizens. "I have been phoned by people from Venda with indigenous drums, by Afrikaans people who have concertinas in their families dating back to the 18th century."Â This goes to verify that the process of archiving music is for everyone, not just university scholars alone. And that people have a sophisticated understanding of the importance of our music heritage.

She believes that this excitement over such an initiative will soon whither away if it is not nurtured. 'When you are not fed something you will not know about it'Â and will soon forget. The longer term objective of the project is to eventually become a fully-fledged music heritage museum. There is a need for an institution that can be like a museum, she believes. But in breaking with traditional ways in which museums have performed in the public sphere, the project envisages a space where people can walk in freely and accessibly. 'The aim of this is to have a knowledge hub, for those who are educated or not.'Â Unlike the dense, text-centred mode favoured by academic publications, 'we want to place an emphasis on the visual elements as well, by including a wall of fame, for example'Â.

She concludes: "It is a pity that funding has not come through as we had hoped. The imminent World Cup would have been a good platform for us to showcase our history, the memorabilia and indigenous instrument."Â

Imagining the Future

Chatting with Noni began to raise a whole set of questions for me around the importance of memory work, particularly with regards to music heritage. I remembered Yvonne Huskisson, who did similar work on documenting the histories of South African composers. But her work, produced in 1969, has proved to be deeply entangled in apartheid legacy. While seeking to give 'voice' to the under-represented composers of the past, she could not escape the racist tendencies of the apartheid regime.

So what guarantee do we have that such a music archiving project, one that we agree is of importance, will not be 'burdened' by the particular order of our time?

Perhaps this mark of our time is something the project has to carry. If this is indeed the case, then let's be open about it and accept that: A project of this nature reveals much less about the deceased musicians than it does about us. As we seek to present these artists, we are in the process of representing ourselves.

Future generations may be able to get a sense of the kind of questions which we saw as relevant. And maybe, if we are to appeal to the future then such a project would have to be digital and web-based. Or we may face the danger of constructing more and more buildings which speak about ourselves, and how exceptional we are!

Thokozani Mhlambi is an Archival Platform Correspondent and a lecturer in the Department of Musicology, UNISA. He writes in his personal capacity.