Posted on March 14, 2011

Deep wrinkles relaxed in death, erasing all traces of the cheery expression we had come to know so well, Leonard looked at peace. Death came suddenly and unexpectedly and his shocked family were comforted to find no obvious trace of suffering etched on his face. I looked at the still form once so powerfully imbued with life and wondered, what traces are there of this man's 58 years on earth.

Sidima Ndeya, known as Leonard to his friends and employers, passed away on 5 March 2011 after a short illness. He was not a famous man. He lived humbly, making the best he could of trying circumstances and taking pride in small victories. For his sisters and his cousins his death is double tragedy, coming as it does just two weeks after the death of another sibling. For my extended family, for whom Leonard worked as a gardener and a handyman it marks the end of an era of shared memories; he was one of the few people left with whom we could reminisce about our father.

We who knew him, his family, friends and employers will remember him, but where may anyone else find information about his life, should they ever go in search of it? I realise that a slim file in my bookshelf holds a set of clues. Over the years I have become the person to whom Leonard entrusted his small collection of documents for safekeeping. Why me, the employer rather than anyone else? There are several answers to that question. Leonard lived in an informal settlement vulnerable to fire and flood and ongoing removals, not a place where fragile documents were safe; I live securely in a substantial dwelling into which the elements seldom intrude. Leonard was not always confident in his dealing with officialdom. Feeling disempowered by both his language and his station in life he would hand me documents and ask me to make the calls to various officials, etc., on his behalf - to put his case to them or ask for them to clarify certain issues. Having been employed by my family for over thirty years Leonard trusted us, not only to act in his best interests but also not, unlike some of his other employers, to 'abandon' him. I have become the custodian of his documents, his unofficial archivist. Leonard's siblings have accorded me the same status, bringing me the records of his death for safekeeping, trusting me to negotiate with officialdom on his and their behalf.

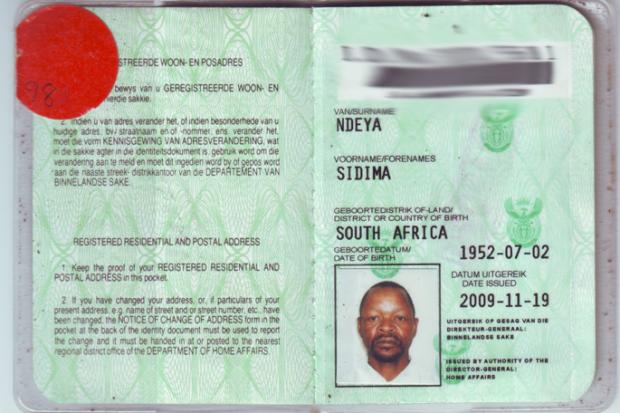

Leonard collapsed on his way to work a couple of days before he died. Brought to our house by a kindly security guard in a delirious and desperately ill state, he insisted that we take a detour on our journey to the hospital so that he could collect his Identity Document (ID) and his hospital card from his home. He was proud of his green bar-coded ID which confirmed his status as a 'S.A BURGER/S.A. CITIZEN'. Born in on 2 July 1952 in a small village in the district of Willowvale, in the then Transkei, Leonard's South African citizenship was revoked in 1976 when the Transkei became the first 'independent homeland', or, as some called it, a 'bantustan', and not restored until after the democratic government was installed in 1994. After years of being disenfranchised and forced to carry one form of 'pass' or another, Leonard treasured his ID as his badge of equal citizenship. As he saw it, the document accorded him all the rights of a citizen and empowered him to fulfil his obligations as a in a democratic state. In the archive of the Department of Home Affairs, Leonard's ID application, with photograph attached, carries details of his date and place of birth and his fingerprints. Importantly, it assigns him a unique 13 digit number allowing future researchers to track his interactions with the institutions of government and the bureaucracy of civil society.

Future researchers with access to Leonards' ID number will find traces of him in the records of the Electoral Commission (IEC). I remember how proudly he voted in 1994 and how profoundly this touched my father, who Leonard long ago adopted as his 'pa' too. I know Leonard was intending to vote in the local government elections this year. When news of the campaign to recruit voters ahead of the forthcoming local elections reached his attention he asked me to sms his ID number to the IEC, just to check that his name was still on the voter's roll. It was, the message came back, 'Sidima Ndeya is registered to vote at Happy Valley Community Hall, Luyolo Street, Blackheath'.

An application for a funeral policy, dated 1991, lists Leonard's address as H119, Plakkerskamp [Squatter Camp], Kuilsrivier. Leonard moved from his home in the Transkei to the Western Cape in search of employment in the late 1970s. Like many others regarded as illegal immigrant by the authorities, Leonard made his home in one of the burgeoning squatter camps. Constantly harassed by officials bent on demolishing shacks and relocating their inhabitants to the 'homelands', living without services and in fear of factional violence life was hard.

Thirteen years after the change of government, Statistics South Africa reported that there were 12 500 611 households in South Africa. Some 8 819 521 (71%) of them lived in formal housing and 1 804 432 (14%) in informal housing. There were 1 459 380 (12%) households living in traditional housing and 417 291 (3%) in other types of housing. On average, 96% of households in municipalities had access to piped water while 85% had access to electricity.

Like millions of other South Africans, Leonard dreamt of owning his own 'brick' house. In June of 2007, the year in which the survey mentioned above was carried out, Leonard received notification from the City of Cape Town's Human Settlement Services department acknowledging an application for accommodation, made ten years earlier. A handwritten note on this card indicates that he occupies House Number HA 143. A communication from the Department of Home Affairs, inserted into the cover of his ID and dated 2009-11-19 confirms his registered residential address as 143 Zola Street Happy Valley, Blackheath, 7580.

Media reports describe Happy Valley, a poverty stricken informal settlement on the outskirts of Cape Town as a dumping ground. Leonard, like the other residents of this ill-named area did not choose to move to Happy Valley, but was 'relocated' there when the land he occupied in the Kuilsriver 'plakkerscamp' was earmarked for a housing development. A post on the Abahlali baseMjondolo website describes Happy Valley in stark terms 'to walk to Happy Valley from east to west, is to walk from established RDP houses to the sad site of the most recent arrivals - dumped on a few square metres by the city with no more than a few roofing sheets, a wooden frame and black plastic sheeting... not unlike a refugee camp in Sudan or Congo... a water-tap every few stands and portable toilets at the end of the row.' In 2005 700 Happy Valley residents took to the street in people protest, demanding that the city council provide better housing. Police used rubber bullets, tear gas and stun grenades to disperse the crowds. The Sunday Times commented that the unrest was 'reminiscent of the 1980s,' when protests against the apartheid regime reached a height. In 2010 NGO Pulse, reporting on the housing crisis in the Western Cape noted that there was a backlog of over 400 000 houses. While about 9,000 new homes are constructed, the backlog increases by about 20 000 houses each year.

Nothing on the record indicates that Leonard's shack was sturdier than many others and that its green painted exterior stood out in the sea of raw metal and wood structures of those with fewer resources. An astute researcher might examine the records of the Department of Human Settlement and find that as a registered site-holder Leonard was also a landlord. On a plot of about 30 square metres he managed to squeeze four homes, his own and those of his three tenants; each one just large enough to contain two single beds and a few domestic utensils.

Though the card from Human Settlement Services states unequivocally that, 'Council cannot indicate when or where you may be assisted,' for Leonard it was nevertheless a beacon of hope demonstrating governments' will to make good on its promise - to him personally, by name. What was of special value to Leonard was the handwritten note on the card - the name and telephone number of the official who had assisted him. He was, for Leonard, the face of government, 'that man is a good man' he said 'we can phone him anytime'.

Leonard is one of the many who did not live long enough to see their dream of a 'real house' come true. Media reports tell of a struggle for leadership within the Happy Valley community which brought the planned housing development to a standstill. They tell too of ongoing and destructive service delivery protests. Leonard's face won't be found in any of the photographs of angry residents; he was a peaceable man and he like to leave his home early and make his way safely to work before the protests started.

Since the mid 1990's employers have had to register all employees and contribute to the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). Our annual UIF reconciliation statements list Leonard by name, record his ID number and detail the wages paid to him as well as our contribution to the fund. This information will show a future researcher that unlike over 50% of the population, Leonard lived well above the Poverty Datum Line. Leonard has never had to worry about being unemployed but was glad to know that the contribution we made to the UIF on his behalf went into a pot of money from which jobless people could draw. He was proud to know that he could play a part in uplifting his fellow citizens.

Like many who live in informal settlements with rudimentary electrical connections, limited access to clean water, adequate sanitation and waste removal systems Leonard contracted Tuberculosis (TB). Statistics South African reports that, in 2008 the year in which his illness was diagnosed, TB was the leading cause of death, followed by influenza and pneumonia. Of the 592,073 South Africans whose deaths were recorded that year 76,970 died of TB. Leonard was fortunate. Diagnosed early he was well served by the hospital system, especially the staff of the day hospital - a 40 minute walk from away from his house - who insisted that he report at 5:00am every day so that they could observe him taking his medicine. He showed us his hospital card, the letter of application for a social grant provided by the doctor, and his packets of medication commenting that, 'they look after us well'. Medical records show that by 2009 his lungs were clear of TB, and his blood was, as he put it, 'clean', with no sign of the dreaded HIV Aids. These medical records will show too that Leonard's knees were beginning to show signs of arthritis, that he suffered from gout and that his doctor had strongly advised him to give up drinking. In a country where the average life expectancy is 50.8 years, Leonard's death at the age of 58 indicates that he must have been reasonably fit and adequately nourished.

Leonard's death certificate records that he died on 2100-03-05 of 'natural causes'. The Notice of Death, signed by an intern at Tygerburg Hospital describes the immediate cause of death as 'severe pneumonia' and the space in which underlying causes can be listed is blank. It is common knowledge that people whose immune systems are compromised by HIV Aids frequently fall victim to diseases such as TB or pneumonia. In South Africa, where HIV Aids has not been declared a notifiable disease, it cannot be stipulated as a cause of death on official documents. We know, from his medical records that Leonard was not infected with HIV Aids in 2009. We know, because he told us, that he was terrified of contracting HIV/Aids. The death of a younger sibling, who suffered from this debilitating condition, caused him great anxiety and Leonard was tested in the week before his death. The result of this test does not appear in his medical file; it was recorded for statistical purposes only. In 2008 the National South African National Aids Survey estimated that 10.9% of all South Africans over 2 years old were living with HIV; 13.6% of African people in South Africa were HIV positive and; while there is s relatively low incidence of infection in the Western Cape 3.8 % of the population are HIV positive. While younger people are more at risk, 6.2% of men between the ages of 55 and 59 are HIV positive. Who knows what conclusions our future researcher may draw from these findings?

Some years my parents took out an insurance policy to provide for Leonard in his retirement and to cover his funeral costs. In the early years, annual investment statements were posted to Leonard at my parent's former address, 11 Kommissaris Street, Welgemoed, 7530. A letter written to the insurers after the death of my father, signed by both Leonard and my mother and certified by the South African Police Service, requests that these important communications be directed him at to my address. Marked for the attention of the policyholder, the receipt of these statements made Leonard feel like a man of means, he reviewed the documents with deep seriousness, nodding sagely before handing them back to me for safe-keeping. Our future researcher might well interrogate these documents and wonder about the complex and enduring relationships that bound employers and employees together through the apartheid years and beyond.

Although Leonard hadn't returned to his childhood home since the death of his parents many years ago, we know that his siblings will bury him, as is proper, in the land of their ancestors. Confirmation of this is found in an invoice from the Funeral Undertakers listing a charge of R5,500.00 for transport to Willowvale in the Eastern Cape. This invoice, which also details charges for an open-face oak coffin, removal, storage and embalming of the body does not cover the cost of a 'traditional' funeral. In addition to the charges listed, Leonard's family is expected to purchase and slaughter at least two sheep, and to provide a fitting feast for the residents of their ancestral village.

Leonard's grave may or may not be marked, but its location is likely to be recorded in a burial register. This may lead our future researcher to learn something of the community in which he was raised and to weave his story into that of an extended family. Finding confirmation of his Xhosa ancestry and upbringing may even cause our future researcher to draw on other evidence to make assumptions about Leonard's rural childhood and the rituals and customs that marked the important events of his life.

It is possible to piece together the sparse evidence that exists in the documentary record and to understand something of the life Leonard lived. What is lost forever though is the singular detail of an individual life: the record of one man's thoughts and feelings, his dreams, fears, frustrations and reflections that might allow for a more nuanced reading of the overarching narrative. In the presence of Leonard's mortal remains I was struck by his absolute absence. All that is left are the ephemeral memories and the records - the archival fragments.

Jo-Anne Duggan is director of the Archival Platform