Posted on February 24, 2012

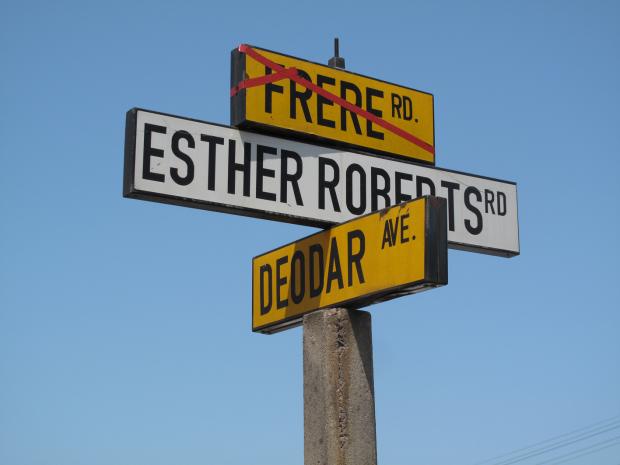

Renamed streets, eThekwini, 2010. Photograph credit: Jo-Anne Duggan

'We have always contended, since the early days of the struggle against apartheid, that the names of buildings and places directly associated with the worst excesses of our colonial and apartheid past would have to change to allow for a process of healing and reconciliation. We have always maintained that the symbols of our past oppressive regime will have to give way to appropriate symbols of democracy.' IFP Media Statement, May 2007

Ever thought about street names as an archive of sorts, a resource that is available to use in the present, to make sense of the past, as markers of history, symbols of oppression or vehicles for healing and reconciliation?

The eThekwini Municipality's street renaming process, is but one of many across the country that has been marred by controversy. In December 2011 the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA), judgement the matter between the Democratic Alliance versus eThekwini Municipality, ordered the municipality to remove all signage indicating the (new) names of nine renamed streets, because it found that the municipality had not complied with its own policy, applicable at the time. The SCA dismissed an application for the renaming of 99 other streets and or public buildings to be set aside arguing that the processes for public participation, as set out in an amended policy had been followed correctly in respect of those.

But is this case really about whether the council is following due process? I think not. I think it has a lot more to do with history and memory and the way in which what we (or others) remember illuminates what we (or they) choose to forget.

'Forget' is a loaded word. Sometimes used to denote a passive absent-mindedness, it can also be malign; associated with the actions of expunging, erasing, obliterating or editing out. When we (or others) choose to forget, we can do so for many reasons. Some South Africans have been urged to 'forget' the difficult past in the interests of national reconciliation; others would prefer to 'forget' a past they are ashamed of.

So who is being 'forgotten' in eThekwini, and who is being remembered?

The municipality's 2001 guidelines for renaming suggest that: except in exceptional circumstances, streets should not be renamed after living persons; that every effort should be made to use the names of people from KwaZulu-Natal; and that the new names should reflect the history and cultural diversity of the city. Fair enough, but how does this play out in practice, in a city characterised by deep historical and political divisions?

The list of 'old' street names, i.e., those identified for 'replacement', include names associated with colonial rule or apartheid rule: Aliwal, Grey, Smuts, King George V, Prince Alfred, Victoria, Queen Mary, Shepstone, etc. 'New' street names honour the heroes of the liberation struggle, including: Samora Machel, Helen Joseph, Joe Slovo, Adelaide Tambo, Steve Biko and Pixley KaSeme.

Some of these 'new' names have generated a great deal of controversy.

Kingsway has been renamed in honour of Andrew Zondo, an African National Congress (ANC) cadre who was executed after he was found guilty of a bomb attack on a shopping centre in Amanzimtoti, in December 1985, in which three civilians were killed. Debates about the renaming of Kingsway, which passes the shopping centre, have brought into play the question of how Zondo is remembered. Some speak of him as a merciless, cold-blooded terrorist. Others view him as a freedom fighter, a hero, a martyr and a true son of the soil, executed by the apartheid government for carrying out the instructions of his commanders.

The renaming sparked an outcry. Civil society organisations, members of the local community and opposition parties and others slammed the action as 'terribly insensitive'. On the 25th Anniversary of the bomb blast, Afriforum hosted a wreath laying ceremony at the shopping centre in memory of the victims and Afriform Youth hung a placard reading 'Murderer Street' over the street sign. Historian Ken Gillings, who had lodged and official objection against the new name said, 'I am absolutely appalled by this ... it has destroyed every vestige of reconciliation that Nelson Mandela strived for'.

In a second highly controversial case, Mangosuthu Highway in Umlazi was renamed after ANC activist Griffiths Mxenge, provoking an outraged response from the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). An open letter from the IFP to the KZN Premier argues that, 'renaming the highway is highly provocative; not because Mr Griffiths Mxenge does not deserve to be honoured '“ there are several roads in Durban that can be named after him - but because the ANC sees fit to replace the remembrance of an IFP leader with that of an ANC veteran'. This is not the only case where Buthelezi's name has been removed and replaced. A statement issued by the IFP in December 2011, in response to the renaming of the Vryheid facility previously known as the 'Mangosuthu Buthelezi Council Chamber' decries the ANC's efforts to, 'eradicate Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi's legacy from history' and calls into question the ANC's commitment to reconciliation saying, 'We are shocked because they talk reconciliation but their actions say something else'.

Is this an issue for the courts to resolve? Recognising that the decision about what streets to rename, and what new names are given is inherently political, the SCA judgment argues that, 'The appellant contended that some of the new names are provocative and insensitive. It is apparent, however, that these denouncements derive from the appellant's political perspective, which is obviously not shared by the majority party. From a political point of view, the appellant may be right, but bad politics is something for the electorate to decide. It is not for this court, or any other court, to interfere in the lawful exercise of powers by the council on that basis.'Â

So what is in a (street) name, and why has the naming and renaming process generated such a heated response in South Africa? An article by Mia Swart (1), published in the German Law Journal argues that names hold great symbolic value in the process of memorialisation and that the process of renaming can be a powerful expression of political change. Swart suggests that changing street names can serve: as a vehicle for memorialisation or commemoration; as a form of symbolic reparation for human rights abuse; to construct a politicised version of history; and as a mechanism for transitional justice, restoring dignity and public recognition to victims. Swart, acknowledging Jordan (2), notes that 'Plaques and names constitute a form of collective memory refracted through political and bureaucratic processes,' allowing 'an official version of history to be incorporated into sphere of social life which seems to be completely detached from political contexts or communal obligations'Â. The challenge is to counter the reminders of past injustices that mark our urban landscape; resolve the tension between preservation and restitution; counter discriminatory and hurtful narratives and deal with the complex nuances of our multi-layered history.

We need to ask ourselves, what is at stake when the names of our streets, public places and buildings reflect a narrow spectrum of history? What is lost, or gained when a particular version of history is privileged and another excluded? What lies at the heart of the controversies around street naming is the question about how to deal with a difficult past. What is certain is this debate is far from over.

Jo-Anne Duggan is the Director of the Archival Platform

(1) Swart, M. 'Name Changes as Symbolic Reparation after Transition: the Examples of Germany and South Africa'. In German Law Journal, Vol. 09 No. 02.

(2) Jordan, J. (2006) Structures of Memory, Understanding Urban Change in Berlin and Beyond. Standford University Press: Stanford