Posted on January 19, 2011

Weintroub argues that the Bleek-Lloyd Collection has been used as a:

'trope' of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity ..., the result of an encounter between colonized and colonizer, to become redeployed and presented as a redemptive interaction in which roles are romanticized and hero-ised, and disturbing/uncomfortable aspects downplayed ... The reconstitution of the archive as 'archive of truth', repository of the nation's pain, and site of national recovery, however runs the risk of silencing the unsettled and unresolved nature of the past.'(1)

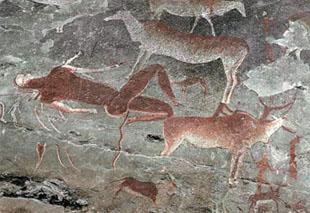

In the /Qe exhibition (LLAREC at the centre of this exhibition) and the Origins Centre at Wits as well as recent publications rock art is being interpreted as that of shamanism alongside essentialist notions of /Nu speakers 'half-animal' images, hunters, timelessness, trance and 'aboriginal'. Some scholars like Mathias Guenther and Andrew Bank suggest that rock art is not primarily of a spiritual nature, but is most frequently associated with physical survival and social interaction or literal meanings. In fact, there is very little of evidence for shamanism or the 'trance metaphor.'

Janette Deacon suggested in 2006 that a conservation management plan was needed to draw together 100 known rock art sites across South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe in conference of World Heritage Status to Mapungubwe Cultural Landscapes.(2) Replicas were deemed to be important conservation mechanisms and the circulation of digitized images was encouraged, especially given the high visitor numbers. (3) TARA deems all rock art to be a world heritage. TARA is a non-profit NGO, registered in Kenya and America and committed to the conservation of Africa's rock art heritage through the setting up of a digital archive of rock art images. It receives support from the Ford Foundation, the Andrew Mellon Foundation and the National Geographic Society. TARA is digitizing over 20 000 images of African rock art for its online archive ArtStor, which provides access to researchers and students across the world. Integrated rural developmental projects include ecotourism, craft projects and other income-generating community education projects and national policies favouring the use of San culture and languages.(4) The Policy on Digitization makes provision for copyright of digital images to receive priority above intellectual property rights of bona fide interest groups.

At the centre of the debate on digitization is that WHS of rock art sites will produce a global economy with rock art no longer belonging to descendent communities but to the world. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett argues that the inscription of intangible heritage on to a World Heritage Site list changes the relationship between culture and the 'owners or authors or orators' who identify with it. In her analysis the WHS List is a homogeniser while the diversity of cultural artefacts is ignored it becomes a listed item for global and universal 'humanity' to benefit from with no one having special claims to it.(5)

Siona O'Connell and Verne Harris describe many post apartheid archives as 'white spaces' where little efforts have been made to give access to images for descendant communities.(6) O'Connell criticises digitisation within the confined institutional space of the Bleek-Lloyd archive, and the re-cycling of images of Bushmanness or otherness. O'Connell points out that the usefulness of the digital project on San communities and the people of !Kwa ttu or any bona fide communities will produce no impact because the very people that it hopes to serve are being sidelined and excluded in the process of decision making. For her it is an illustration of how colonialism remains embedded in the archive. She criticizes UCT, the Manuscripts and Archives Department and LLAREC (with Skotnes as its director and moving force) for not having established any dialogue on participatory processes in order for these images to be freed from white controlled spaces. O'Connell notes that in Skotnes's digital LLAREC archive there is not a single essay by a Bushman, or even evidence of permission having been granted by San groups, or access to this resource being granted to anyone from the !Kwa ttu group. How it is possible, she asks, for UCT to be oblivious to these matters of digitisation? The Mellon Foundation, an ALUKA partner, De Beers, Scan Shop and UCT largely funded the LLAREC in the name of research and education. O'Connell is at a loss to explain UCT's 'celebration of digital culture and internet of image-Bushman whilst marginalizing their subjects'. (7) The 'digital divide' between bona fide interests groups and institutions has become apparent. The digital archive sanitizes sensitive, emotional material, such as images of dislocation, death and violence to produce aesthetically pleasing displays that would appeal to white audiences.(8)

O'Connell's research uncovered the dimensions of the gallery space or now the virtual library as 'mediated sanctum' that takes over the world of the art object. The 'Bushmen on show' become synonymous with real, lived experiences, as males are employed as low paid tour guides and hunting trackers, while females work as cleaners and waitresses at the Kwa-ttu centre while white capital and Western frameworks informs decision making. Maseko Emmanuel, an elderly !Xun man, expressed the notion that death, memory and forgetting, power and injury are caught up in performances in response to the LLAREC archive. In addition, anger and sadness of the dead subjects in the photographs who are unable to defend their nakedness were expressed.(9)

The 'digital divide' will produce the same stereotypes of race while communities remain marginalised and on the peripheries of economic wealth while images via digitisation are produced for tourist consumption. The digitisation projects aim to lend coherency to images taken from broken or fragmented records while images are often decontextualised and the specificity of events removed. The Policy on Digitisation does not address the problem of remaking meaning or the 'violence of the colonial camera' and images.

(1) J. Weintroub, 'From Tin Trunk to World-Wide Memory', 36.

(2) J. Deacon, 'Rock Art Conservation and Tourism', Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 13(4), Dec. 2006, 391.

(3) Ibid, 385.

(4) http://www.africarockart.org/home/. 'African Rock Art is amongst the oldest surviving art, predating writing by tens of thousands of years. TARA, the Trust for African Rock Art, is dedicated to the awareness and preservation of African rock art'.

(5) Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 'World Heritage and Cultural Economics', 1-2.

(6) V Harris, V. Harris, 'The Archival Sliver', 'in C. Hamilton at al, eds., Refiguring the Archive, pp. 135-159.

(7) O'Connell, 'No f-stop for the bushmen', 65-74.

(8) O'Connell, 'No f-stop for the bushmen', 49-53.

(9) Ibid., 53-57.

Mona Hendricks is a Reading & Writing facilitator for Academic Literacies at UNISA Johannesburg and has recently completed an MA in Public & Visual History at the Universiyt of the Western Cape. She writes in her personal capacity.