Posted on June 22, 2011

Some people in Cape Town and the Western Cape would argue that searching for one's origins, identity and cultural heritage is a fruitless venture best left in the past. I beg to differ. This knowledge is an important tool to confront negative perceptions and stereotypes that blacks hold on coloureds, whites hold on blacks and coloured hold on coloured etc. The Western Cape and specifically Cape Town's community is in a racial mess as a result of the past. By dissecting heritage, we can find the negative perceptions seemingly innate to the different races of the Western Cape.

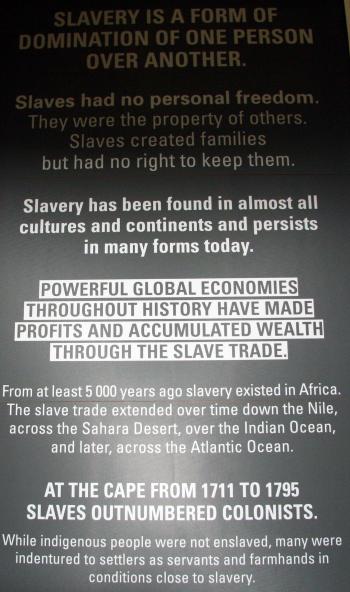

Should one trace the Cape's bloody history since the middle 1600's, one would come to a greater understanding of our modern Mother City. It would probably become clear that the historical cycle of contempt between blacks and so-called coloureds merely rusts the slave collar around our true identities. This cycle only mirrors the slave mentality which was always needed by Jan Van Riebeeck, Simon Van Der Stel, Van Jaarsveld, Bergh, Surrurier, Roux and other landowners who had control over the City during colonialism and Apartheid. To overcome the slave mentality now, one needs to understand one's past. But in all honesty, can our people, not only of the Cape Flats or townships answer this; what is your heritage?

The question can easily be answered. As Tariq Mellet, a heritage activist, articulates within this framework, identity in the Cape includes exploring, the San, Khoe and amaXhosa, African and Malagasy slaves, Indonesian slaves, soldiers, sailors, labourers and manumitted slaves, Marooned local communities such as Springboks, Bergenaar Basters, Orlam Afrikaners, Griquas, Indonesian Muslims and exiles, 'Creole', Paranakan Chinese exiles from Batavia, refugees from the Phillipines revolution, Mazbiekers, Prized slave boys and girls, Congolese indentures, Mozambique indentures, Malawian indentures, baTswana indentures, the Kru from West Africa, the Siddis from Zanzibar, the Oroma from Somalia, the Saints from Saint Helena, and the Seamen from many nations. Is it not evident that constructed racial divides cannot exist within a nation with such an expansive history? As current anthropologists would agree, a 100% white, black, coloured, Indian or Chinese person or race within South Africa cannot exist in isolation. South Africa's collective heritage is a kaleidoscope of races, nations, classes, religions and languages. But still, there is a race classification evident in this modern society.

If you were to research the sickening volume of slave trading you would come across the Oromo people from Ethiopia who were trafficked from Ethiopia to the Red Sea and then to Lovedale in the Eastern Cape. Most of them women and children in the latter part of the 19th century, many inter-cultural marriages took place then, and as a result the population of the Eastern Cape expanded and grew. Within the neighboring Western Cape, after the universal call for the emancipation of slaves in 1834, farmers in the Drakenstein district of the Cape, continued to import indentured laborers from Botswana, Malawi, Congo and Mozambique up until the late 1800's. Many remained in South Africa, with most marrying into Coloured and Xhosa communities.

This is but a fraction of our individual and collective selves. The Oromo people's story got scant attention from historians and has only recently been acknowledged as a significant component in the reconstruction of the history of slave sites in the Eastern Cape. Remembering the shame of our collective past will bring voice and expression to our angry, violent communities born into and out of slavery at the Cape. Through reflecting on urban Cape Town's pre-Apartheid Colonial thinking we can begin to understand who the victims are and identify the perpetrators of this legacy.

The paradigm of RACE classification or identification, originates from colonialisms' 'Slaves, free Blacks, Europeans, Marooned communities, Exiles, Refugees, Indentures and Migrants'Â. From this paradigm of race classification, a race hierarchy encouraged a chauvinistic thinking; ever present from colonialism through to Apartheid and carried along to today.

Let's stop fooling ourselves; we have remained racist even within a racially diverse so- called 'rainbow nation'. The poor people of colour on the Cape flats are struggling to identify themselves with privileged whites and black South Africans, while its snobbish elite are continually distancing themselves from their own working class past. What happened?

The xenophobic violence in May 2008 and 2011 in the Eastern Cape is a prime example of just how fatal ignorance of heritage can be. A racial tension between whites, blacks, coloureds and 'other' blacks is shameful considering the racially fluid history. This can be said for all provinces of South Africa, but the hate attacks continue to fill one with bleak despair.

Borders are imperfect. They can be crossed, redrawn by invading armies and even the flooding of rivers can permanently redefine the boundaries of nations. The body is one such imperfect border. Blood will out - through atrocities committed in the name of hate and ignorance. Ignorance of, in one case, a shipment of Oromo slaves from Ethiopia to the Eastern Cape. Sadly, we have been killing family.

The outcome of South Africa's 2011 municipal elections is arguably the current ruling party's most embarrassing moment. As Ferial Haffajee, editor of City Press explains in an article, 'How the ANC lost the coloured and Indian vote', '...all we are are racial boxes to be ticked'. We will have to acknowledge the barriers, move beyond the race politics in government structures. That would mean learning from the past. A good lesson as Haffajee explains 'would be the teachings of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in the 1980's who also taught people like myself about unity, non-racialism and other inclusive philosophies that signified the idea of being proudly South African and African'. This means working with communities across colour bars and presenting worthy young local leaders in the service of all people.

The people of colour are continually identifying each other as 'them' and 'us'. This is 'blacking' out the real RACE discourse and has set the City aside from the rest of South Africa. Remembering slavery in the Western Cape is not just about having a brown skin; Blacks and whites should seriously pay attention. This would mean transcending from singular cultural confinements or constructs like 'White, Coloured, Malay, Black and Indian'. It's only when this is understood that I can start feeling I belong in this City.

The question is; are we all not inextricably bound in this city's shaping? Is it not a part of everybody's history that must be acknowledged? For this city to truly prosper and grow beyond geography, race, class and religious barriers, acknowledgement of a shared heritage is a must. Tariq Mellet explains in his book that 'we need to weave a number of threads and emphasise that there are many ties that bind us' as South Africans and as human beings.' We can either remain in bondage of the negative aspects of our colonial and Apartheid past or truly break free to establish a nation that dreams together and pulls together'

Lucy Campbell is an Archival Platform correspondent