Posted on January 25, 2012

In the early 1980s Shahena applied for, and was granted, political asylum in the USA because she had married a white man in contravention of apartheid law. Shahena, however, returned to South Africa on a number of occasions. A few years ago, I met up with her in Cape Town after a long interlude. At this meeting, we spoke about her mother and her sterling work in helping those who faced forcible eviction from District Six, home to a thriving, multi-cultural, working class community with an irrepressible spirit until it was demolished over a period of 14 years from 1968-1982. Shahena told me she was working on a book about her mother's life, together with a colleague, Donna Ruth Brenneis, who Gool-Ebrahim had befriended while on a trip to the USA in 1988 to share her experiences in regard to forced removals in South Africa with American civil rights activists and others. This was great news, I told her, as a book on her mother's life would go a long way to cementing her place in history as a courageous, compassionate and tireless human rights activist. Her story, I reminded Shahena, needs to be told, for otherwise she would become a forgotten figure, along with other heroic figures from the 'coloured' community who have been displaced from the broad account of South African history.

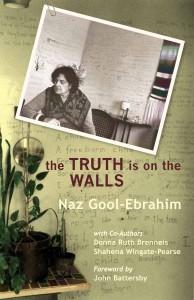

Gool-Ebrahim's book, 'The TRUTH is on the WALLS', a life-story co-authored by Shahena and Brenneis, was launched appropriately on 9 August 2011 - Women's Day in South Africa - at Trafalgar High, a school attended by generations of District Sixers. Of interest about this school is that it was founded in 1912 by Gool-Ebrahim's grandfather, the esteemed Dr Abdullah Abdurahman, president of the African People's Organisation (APO) from 1905-1940, and the first person of colour to serve as a councillor on the Cape Town City Council.

'The TRUTH is on the WALLS' is a combination of sections from a manuscript that Gool-Ebrahim had begun writing in the late 1970s and her oral testimony, as recorded by Brenneis in 1988 in San Francisco. The foreword is written by John Battersby, a journalist, political commentator and Pulitzer Prize nominee who had came to know Gool-Ebrahim during his coverage of the District Six saga. The introduction is by Brenneis, who describes the book as a work of 'historical non-fiction'. The book includes a selection of family photographs, a poem or two by Gool-Ebrahim, as well as extracts from Shahena's journal (she writes to Mother Earth), in which she touches on such subjects as growing up at Manley Villa, her involvement in the 1976 uprising while at Trafalgar High, her marriage across the colour line and subsequent exile, her return to the decimated landscape that was District Six, and the passing of her parents.

Gool-Ebrahim is a great and natural story-teller and 'The TRUTH is on the WALLS' is written in an accessible, easy-to-read style and with eloquence. The book, however, is probably not always completely accurate in historical detail as part of it, according to Brenneis, was captured from 'the top of Naz's head.' This shouldn't, however, bother readers too much as the book is not intended to be a work of scholarly research.

What we are presented with in The 'TRUTH is on the WALLS' is, by and large, a weave of South African history and politics, family history, the struggles of people in District Six against eviction, and Gool-Ebrahim's role as an activist and 'voice of the voiceless' in this context. Says Gool-Ebrahim:

"I tell my story so that the watching world may see more clearly the origin of the storm of racial backlash. I tell my story to give a voice to those who, for too long, have had none. I tell my story so that we may all rage together at the tyranny of oppression and weep together at its consequences. I tell my story with hope for a future of unity and peace."

The title of the book is derived from an unforgettable, evocative image, as described by Gool-Ebrahim. Manley Villa was one of the last houses to be demolished in District Six. In 1981, a Group Areas Board official - she calls such persons 'Malika Moud' (Angels of Death) - knocked on her door to deliver a final eviction notice. Enraged by the thought of having to leave her beloved home, she began scrawling her anguish and frustration on the walls of the house. On seeing Gool-Ebrahim's messages, prose, poetry and the names of various people who frequented Manley Villa on the walls, someone who was staying at the house painted a sign on the outside wall which read: 'THE TRUTH IS ON THE WALLS INSIDE THIS HOUSE, THE TRUTH THAT IS DENIED'. When the official later returned to Manley Villa, he demanded to know why she had 'vandalised' the house, which, of course, is ironic as Manley Villa was soon to be destroyed.

'The TRUTH is on the WALLS' is divided chronologically into three parts, each beginning with a landmark date in South African history - 1652-1947, 1948-1963 and 1966-1982. The first part provides the reader with a brief overview of colonial history at the Cape, and also deals, among other things, with Gool-Ebrahim's impressions of District Six as a young girl, her ancestry, her life in Tyger Valley as a young person, and segregation before the National Party rose to power in 1948. She also covers her early life as a militant activist (she was a member of Cape Town's India League, which supported passive resistance), opposition to the establishment of the Coloured Affairs Department (CAD) and 'coloured' response to World War II.

The highlight of part one, however, is undoubtedly Gool-Ebrahim's wonderful, engrossing account of the life and times of Cissie Gool, daughter of Dr Abdurahman, and her aunt, source of inspiration and mentor. About her, Gool-Ebrahim has much to say, in respect of both her political life on a stage dominated by men and their close, warm relationship. Known to the people of District Six as 'their own Joan of Arc', Gool is a vitally important and legendary figure in the history of 'coloured' liberation politics at the Cape, as acknowledged in the book. She was an enormously influential figure, a socialist and a gifted orator who spoke out against injustice at every turn.

As indicated in 'The TRUTH is on the WALLS', Gool's name is stamped all over the history of 'coloured' political organisation and resistance at the Cape from the 1930s to the early 1960s. In the book, Gool-Ebrahim walks us through the many liberation organisations with which Gool is associated. She founded the radical National Liberation League (NLL) in 1936, which took a stand against 'white capitalist imperialists', and was also elected president of the Non-European United Front (NEUF) in 1938, formed to coordinate organisations into an anti-segregation front. Then she was also vice-chairwoman of the Cape Passive Resistance Council, established to oppose the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act of 1946 (known as the Ghetto Bill), which authorised the removal of Indian people from their established trading and residential areas. In addition, she was active in the Franchise Action Council, which challenged the elimination of 'coloureds' from the common voters' role in 1951. And besides all of this, she was the first 'coloured' woman councillor to serve on the Cape Town City Council, representing District Six from 1938-1951.

As clearly conveyed by Gool-Ebrahim, Gool was a woman of great substance and charisma, and one of the Cape's stand-out personas of the 20th century, if not of South Africa itself. Her first-hand account of the 'Jewel of District Six', as she was called, is invaluable, particularly because, as far as I know, not much is available in the public domain about Gool's life and contribution to liberation politics, brief biographical details on the Internet aside.

The second part of the book, although much shorter than the first (22 pages compared to 76), is, nevertheless, just as diverse and multi-faceted - a sort of carefully orchestrated mosaic of ideas. It includes topics such as life under apartheid, Gool-Ebrahim's love affair with, and marriage to, Hari Ebrahim, the passing of her mother, the 'coloured' 'brain drain' to countries like Canada and England in the late 1950s and 60s, and harassment by the police and Special Branch. Gool-Ebrahim also discusses political militancy in the schools of District Six, particularly at Trafalgar High, the history and role of the Congress movement in the liberation struggle in the 1950s (she joined the ANC in 1991), and the death of Gool.

In part one of the book, Gool-Ebrahim presents a somewhat romanticised and utopian view of District Six, centred around its 'multi-racial' character. Nevertheless, her conception of the District is a powerful counter-narrative to the official apartheid view of the area - that it was nothing but a crime-infested slum, which was the pretext for its destruction. This is what she has to say:

"Before apartheid was introduced in 1948, ethnic and cultural differences were unimportant in the District. Although there were numerous, complex problems confronting everyone in the community, a one-big-happy-family existed whether we were black, white or brown and we ranged in shade starting from midnight blue. A preoccupation with skin tones wasn't part of our upbringing, training or system. We were aware of the existing colour bar, but we didn't allow it to bother us on a social level… The District could have been a model for any village community anywhere in the world. My heart is sore just thinking about the idea."

After District Six was declared white in 1966 under the Group Areas Act (1950), Gool-Ebrahim's ideal world of 'multi-racial' harmony came tumbling down, bringing heartache to some 60,000 residents. In part three of the book, she describes District Six on its last legs and the despair of its inhabitants. But it is not just a picture of victimisation and desperation that she creates here, as what emerges in this section is a portrait of Gool-Ebrahim as a dedicated human rights activist, who conducted a noble struggle against the forced removals in, and the complete demolition of, District Six. More particularly, she discusses her work with the Women's Movement for Peace (she was an executive member from 1976-1990) in the context of forced removals and the role and activities of the District Six Rents, Residents' & Ratepayers' Association, established in 1979, and of which she was chairperson. Largely because of her drive and commitment, and also that of Father Basil van Rensburg, her comrade-in-arms who nicknamed her 'Naz-Raz-A-Ma-Taz', 'Silence [in District Six] was replaced by hope and courage,' as she writes.

'The TRUTH is on the WALLS' ends on a moving note. Manley Villa, symbol of the District's help mekaar (help each other) ethos, was home to the Gool-Ebrahim family for 22 years, from 1959 onwards. After returning from a speaking tour of the USA in 1982 to inform the international community about the horrors of forced removals, Gool-Ebrahim discovers that her family had been forced out of their home in her absence and moved to a flat in Gatesville on the Cape Flats. Just before Manley Villa was to be demolished, she pays a last visit to her former home, accompanied by her four-year-old grandson, Neefa. By now the bulldozers had moved up the hill towards the mountain, having begun their destruction at the lower end of District Six, and had reached the vacant house next to Manley Villa. 'Naza,' says Neefa, 'I want to pee on the bulldozer,' which he did, exclaiming, 'Naza, I pissed on the bulldozer!' 'Any form of resistance,' writes Gool-Ebrahim, 'was a victory over apartheid and symbolised a family tradition.'

Gool-Ebrahim was no Mandela or Tutu and struggled with the notion of forgiveness. Here is a passage from 'The TRUTH is on the WALLS': 'Today, I still wonder how can I forgive the National Party, many MPs, Government puppets, collaborators, the military, police, 'The Group', Special Branch and right-wing political extremists for the rape of my family.' She passed away in 2005 in Belhar on the Cape Flats, probably as a broken, heartsore woman who would have chosen 'real' justice above forgiveness and reconciliation as a way of closing the door on South Africa's colonial and apartheid past - that is my understanding of her, anyway. Thanks to the efforts of Shahena and Brenneis, we have her book, a touchstone to her memory and legacy. It is dedicated to 'All South Africans who were uprooted from their homes under the Group Areas Act, and the people of District Six whose tears cannot blot out the trauma of forced removals.'

Emile Maurice is an independent arts writer and curator