Posted on December 13, 2011

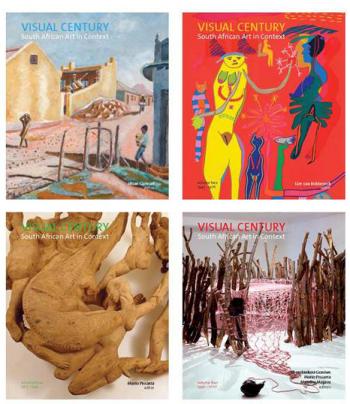

This history had to be largely told by South Africans, Jantjes was the project director and Mario Pissarra was appointed in 2007 as project manager and editor in chief. Lize van Robbroeck assisted in creating the framework for the book, each one of the four volumes had one or more editors and 33 experts (local and international) were involved.

It is a beautiful publication, richly illustrated with full colour photographs; as can be expected, contributions vary in quality, but on the whole the research is sound, the texts readable and extensive footnotes, as well as the timeline, guide the serious reader to more information and sources.

Numerous publications about South African art have appeared since the 1990s, but nobody has attempted to produce a comprehensive account from a post-apartheid perspective and in the context of national and international art practice and art history. The four volumes are arranged chronologically but the art is approached thematically.

At the launch of Visual Century in Johannesburg, Verne Harris, Head of the Memory Programme at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, referred to the publicity claim that the book 'makes a major contribution towards the construction of an inclusive national archive' and noted its potential strengths and vulnerability: 'For its own meaning and significance, and value, will ultimately become located in the contexts of its own production, and in the contexts within which it will be read and used.' He suggested four fundamental measures by which the contribution or not of Visual Century to the realisation of a 'decolonised post-apartheid' may be evaluated. I would like to venture a response to Harris' questions.

Firstly: 'Does it escape the totalising instinct of metanarrative construction? Is it challenging old metanarratives only by reproducing them or by generating equally claustrophobic new ones?' He applied the deconstruction test and in terms of postmodern critiques of meta-narratives, Visual Century is successful: there are many writers, voices, stories and perspectives and a number of artists who have received little or no attention in the past, are acknowledged and discussed. This plurality and the overlapping periods have, however, resulted in duplication. Although it is refreshing to encounter artists' work in more than one context, this, as well as the repetition of facts and events, becomes boring in parts, particularly if one reads the volumes from beginning to end. My view on the second part of the question is partially expressed in my response to Harris' third and fourth questions.

Secondly: 'Does Visual Century resist - for it can never fully escape - the old colonial habit of relying on experts to ensure that learning takes place for non-experts?' Harris referred specifically to the positions of power in which experts find themselves and their almost 'paternalist influence over when and how memory is constructed.' The involvement of experts in such an ambitious project - for better or for worse - is unavoidable; writers include art historians, museologists, curators, artists, art theorists, literary scholars, poets, urban geographers and cultural activists. This broad approach and the voice of Vonani Bila in Nessa Leibhammer's chapter 'Re-evaluating traditional art in a South African Context' resist paternalism.

Thirdly. To what extent does Visual Century tend what Harris calls the 'bruised places', the 'colonial' silences, the secrets, taboos and lies that will not go away? For him post-apartheid South Africa offers less than a fertile environment for the ideals of transparency, freedom of information and truth-recovery. And this is another test for the book: 'How successful has it been at declining any dictate to turn away from these places, to pretend that they are not there? How courageous has it been in going to where it is painful, and where it is painful to go?'

There are excellent articles about the bruised places and psyches of apartheid that expand our knowledge of our visual history and archive exponentially. But a major shortcoming is the lack of engagement with the failures and successes of South Africa over the past 20 years, a time of profound political change. Volume four, which covers the years 1990-2007, is particularly disappointing in this regard.

In his contribution, 'Great Expectations A view from Europe' Jantjes appropriately tackles government for its neglect of our visual artists and art. Andries Oliphant concludes his chapter 'Imagined Futures Some new trends in South African art' with the observation that the '...democratisation of South Africa has ... not inaugurated a post-colonial utopia; rather it has lurched from apartheid to the brink of a fullblown dystopia.' He lists some of the demons of our society: 'a health pandemic [has HIV/Aids become an unmentionable?], unemployment, intolerance, xenophobia and a plethora of other social, economic and environmental ills...' and imagines that the 'art of the future...should and will play a leading role in creatively engaging these problems in the continuing quest to humanise the world.'

The problem is that artists have been doing this for some time now, but Visual Century does not deal with the bruised places and pain of our democracy. Where is the chapter on HIV/Aids and the extraordinary art that has been fuelled by it since the 1990s? Where is the environment, global warming and land art? How can this visual century be described without Zapiro's cartoons and other works that deal with contemporary issues and challenges?

Visual Century concludes in 2007, but because the project took so long there are references in many texts to more recent articles and books, so there can be no excuse that, for example, the secrecy law (which was in the making before its introduction in 2008) is not mentioned.

Federico Fresci writes two articles on the decorative programmes in public buildings that promoted Afrikaner nationalism, but Constitution Hill and its groundbreaking architectural and art programme (one of our great success stories) gets but a mention (in the same sentence as Metro Mall and Faraday Market) in Zayd Minty's 'Public Art Projects in Post-Apartheid South Africa Visual culture, creative spaces and postcolonial geographies', while the City of Cape Town's Memory Project is worth only a footnote. What about the memorial projects and new museums that have been created since 1994?

To fill this glaring gap I recommend that you read Jonathan Noble's book African Identity in Post-Apartheid Public Architecture White Skin, Black Masks. At the core are five public architectural projects: The Mpumalanga Legislature, Nelspruit; The Northern Cape Legislature, Kimberley; The Constitutional Court of South Africa, Johannesburg; The Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication, Kliptown; Freedom Park, Pretoria. These politically prominent projects are notable examples of contemporary public buildings that have resulted from competitions and they showcase different kinds of architecture in a variety of locations. They set the scene for Noble's post-colonial perspective on political transformation and its ramifications for architecture in an evolving African democracy. The role of decorative themes associated with African idioms and experience, as well as the involvement of artists and craftspeople in the creation of new imagery and surface treatments, are explored in depth.

Here I already touch on Harris' fourth test: 'To what extent does it enable readers, at one and the same time, not to be alienated from the future and not to be overly at home with it?' He believes that societies, and possibly individuals, learn most readily not from the past but from the future. Visual Century is a valuable source and contribution to the literature on South African art, but there is little about the present, let alone the future (this includes the selection of images in volume four).

There are exceptions: In his contribution 'In Human History Pasts and prospects in South African art today' Colin Richards discusses, among others, works inspired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and he affirms that 'art is of profound and abiding human consequence - in power, in strangeness, in openness - part of the unfolding history of now.' From 1990 art begins to give us a glimpse of what it might mean to be free, allowing us to imagine that the struggle of becoming fully human is never over. Insofar as a critical humanism links the aesthetic and the ethical, art and politics, it continues aspects of South African resistance art before 1990 while at the same time paradoxically beginning to free us from the obligations of that time.

In the 'The Experimental Turn in the Visual Arts' Kathryn Smith reminds us of the numerous collective practices and public events that were spawned by the sense of freedom that came with democracy and the concomitant unfettered engagement with the international community. She states: 'The energy of the early 1990s art world has not been equalled in the subsequent decade' and scrutinises the reasons for this. She offers keen insight into what the future may hold.

Accessibility will be the acid test for the future meaning, impact and value of Visual Century. The texts are readable, sometimes compelling, but how broad an audience will be reached is debatable; the hefty price tag of R1 500.00 will no doubt deter many an art professional or lover, student and artist. Readers will judge and time will tell.

Marilyn Martin is an art historian and former director of the Iziko South African National Gallery.