Posted on December 13, 2011

The official opening of Hostel 33 as part of the Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum Somerset West has raised significant issues regarding the recognition and commemoration of spaces associated with the migrant labour system in the Western Cape. There are wider issues too - those associated with memory, identity and the significance of early segregated and restricted spaces - in particular; areas developed for black migrant labour in the Cape Peninsula and spaces that may be seen as a prototype for the development of spatially segregated living environments.

In his address at the opening of Hostel 33 Professor Leslie Witz mentioned the Zwelihle labour site in Somerset West - a rare surviving example of an intact, racially segregated, private labour compound in the Western Cape.

Zwelihle was developed in the early twentieth century to house black migrant labourers at the De Beers Explosive Works (later African Explosives and Chemical Industries Ltd). This site currently forms part of the Somerset West Heartland (Pty) Ltd land holdings, parts of which are currently being developed. The full industrial site is extensive - covering over 400 -500 ha and was originally used for the manufacturer of blasting explosives, nitric acid, cordite and later chemicals, paints and fertilizer.Industrial manufacturing ceased two decades ago and most of the industrial area currently goes unused. With one or two significant exceptions including a fumigation room, all structures at Zwelihle remain.

A medical report of 1901 on conditions at Zwelihle provides some indication of the initial living conditions. It stated that the men initially lived in the prototypical long corrugated iron dormitories similar to those at De Beers in Kimberley. Each room contained 12 men. There were no windows - only ventilation shafts. The ill health of the men at the time of the report suggested that the living conditions at these barracks or dormitories were poor. The report also stated that at this time there were 159 Coloured and 690 black workers ('Natives' in the language of the report) living on site at De Beers. The compound was not initially closed but similar to the 'quarantine style' or controlled system as imposed at Uitvlught.

De Beers Explosive Works and AECI, later drew on further experience gained on the Kimberley mines in the recruitment of black labour; and in the development for a spatial prototype for an enclosed private migrant labour compound at Zwelihle. The system included strong administrative and spatial control, racial segregation and complete dominance by the work environment. The final product at Zwelihle was enclosed and inward orientated, with ventilated and windowed brick dormitories being grouped around a central yard which contained laundries and ablution facilities and later common rooms and dining areas. The site was separated from the wider area by a series of buffers; including a wall, a railway line and a dense band of trees. There was a single access and egress point, which was controlled. Workers were railed in and entered at the control gate. The allocation of spaces was based on a hierarchy controlled by the indunas who mediated between the workers and the management. The Indunas had their own houses and washing facilities.

All personnel requirements were met within the enclosed compound including administration, a postal service, food allocation, licensed premises, a beer and braai area and laundries with washing facilities, including for blankets. There were no common rooms and initially no dining areas. Men ate in their rooms or outside on the bench provided.

This spatial arrangement of the buildings, the inward looking and controlled nature of the space and the complete segregation of the migrant workers, within the context of a deeply hierarchical working environment, provide clues about attitudes to race, labour and settlement in the Western Cape. Access to and from the site was so controlled and separation so complete that in 1945 few residents of Somerset West were aware of a 700-1000 strong labour force in their midst.

A hidden space

The 'hidden' nature of Zwelihle was re-enforced by apartheid laws which controlled and restricted movement, work and settlement. Upon arriving the men were issued with a pass, linked to their labour contract, by the resident magistrate in Somerset West. They were contract workers, and once their contract expired, had no further right or permission to remain in terms of apartheid legislation. Productivity was an incentive to be re-contracted.

The hidden nature of Zwelihle and AECI was also evident in its spatial characteristics. The nature of dynamite production on the De Beers Site needed a 'cordon sanitaire' or an extensive buffer space - and within that - a series of 'blast circles'- thick belts and copses of eucalyptus trees intended to absorb accidental blasts and protect the public. To this day very few residents of Somerset West and Lwandle are aware of the massive industrial complex unless they had worked there in the past.

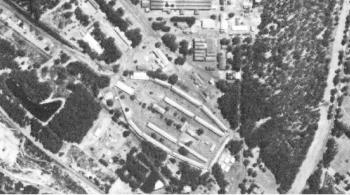

An aerial photograph of Zwelihle in 1967 showing the blunted elliptical shape, the dense growth of tress and the separate inward looking nature of the site with buildings grouped around a central space. The industrial work area is north in the photograph and the graveyards are situated to the south.

Access from the more public administration area to the industrial area was controlled by a security gate. Within this, the hostel site was controlled by a further gate. Although restrictions on movement were later eased, initially at least, the system required workers to remain within the controlled labour area.

Free movement of workers was also controlled and restricted by the pass system. In addition, the closed nature of the compound militated against free movement of workers. Gates were shut and night after workers entered the compound and only opened again the morning. Workers remained on site. They became supporters of the local football club called De Beers AFC and would watch games on the nearby sports fields as well as play football on open spaces made available to them. They also had access to fields for cultivation and would grow mielies. Control of movement eased after the 1980's and certain workers gained the right to have their families with them. Married quarters were built within the compound. A job at AECI was regarded as a good one, generally with adequate pay and working conditions.

Some workers sadly never left. There are three graveyards to the south of Zwelihle including an early graveyard to the men who succumbed to the Spanish flu epidemic. A number of the later graves are of women.

The inner gateway to Zwelihle, which controlled access and egress. The pyramid-shaped buildings in the background are the common room and dining hall.

The work at the Lwandle Museum has highlighted the need to 'fill in the gaps' in the labour history of the Western Cape, and the need to remember and interpret the sites associated with it. There remains an untapped reservoir of memories and experiences about working at AECI and living at Zwelihle in Lwandle itself.

Barrack like dormitories defining a central space. These were built in the mid twentieth century. There were generally about 8 men to a room. Rooms were accessed by a single door with an upper window and a window to the rear. Ventilation was improved by continuous roof ventilators.

The Zwelihle site is relatively intact and rare as a result of its management and retention, pending future development decisions, isolation and private ownership. The intactness of Zwelihle makes it a useful place to examine and understand the interplay between labour management, control and hierarchy within industrial spaces and indeed the relationship to a wider apartheid environment.

The prototypical nature of segregated labour sites has yet to be fully examined in the urban history of the Western Cape. One only needs to look at the original urban design intentions of Langa to understand how segregated dormitory suburbs were based on an original labour compound prototype - the few access and egress points, the nature of the buffer zones, the separation of spaces using the mechanisms of road and rail and the strong element of control. Despite the fact that Zwelihle is now empty - all these elements are still visibly present.

Melanie Attwell is a built heritage and landscape conservation specialist.