Liziwe gets to grips with inter-generational changes in the use of isiXhosa

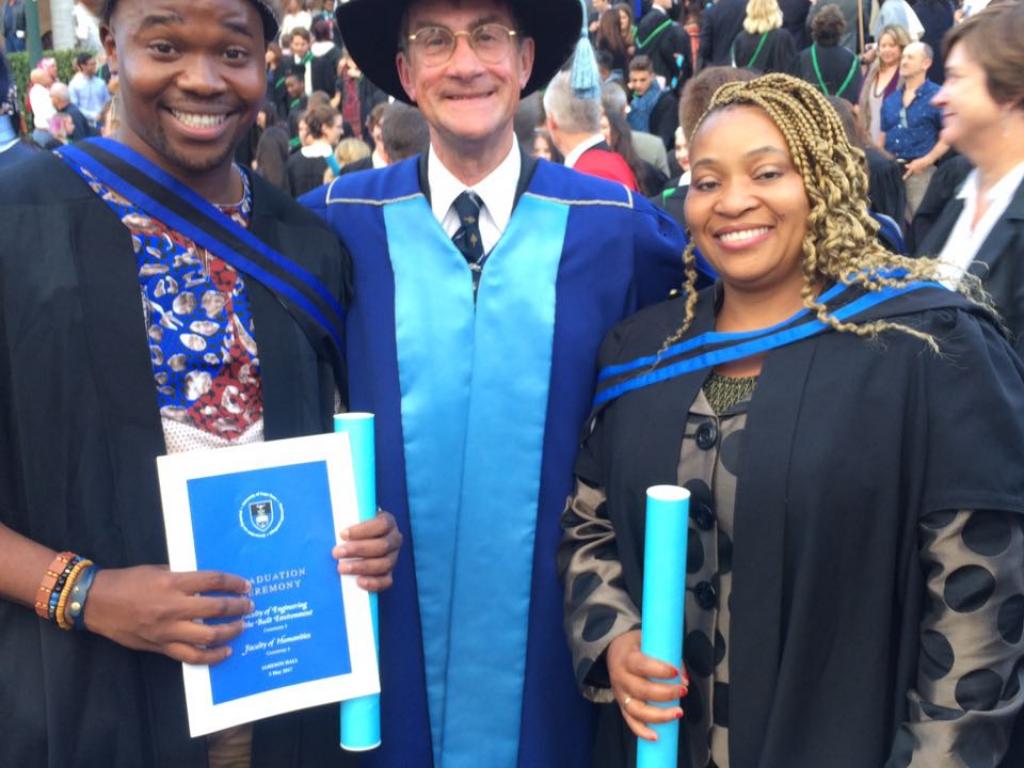

Liziwe (pictured right) with Professor Hugh Corder (centre)

Liziwe Futuse, who is surrounded by language – being the administrator for Mandarin, isiXhosa and Afrikaans in the School of Languages, graduated in May with an Honours degree in African Languages. Her dissertation topic was on the issue of how isiXhosa as a language has changed inter-generationally. She researched her own family’s speech – the isiXhosa spoken by her mother, herself and her own children.

Liziwe’s undergraduate degree was a BA with majors in Anthropology and Linguistics, and she embarked on her Honours because she has always been interested in languages and wanted to develop a more in-depth understanding. Working in the School of Languages made her more aware of language, particularly isiXhosa, and how it is used, as an area of research interest.

One of her surprising discoveries in her research was how different isiXhosa is among different generations. Liziwe was intrigued to discover how easily children can lose the language if it is not used regularly at home, as a result of attending English medium schools. What brought this home was when her daughter attained 5 distinctions in Maths, Science and other subjects, but only got 48% for isiXhosa. She also found it interesting that her mother’s isiXhosa was influenced by her daughter’s idiolect: while her mother speaks perfect isiXhosa, at times she adapts her language to suit the younger generation. Liziwe found that her own isiXhosa is influenced by the English-dominant environment where she works, however many of her colleagues in the African Languages department speak isiXhosa and she consequently becomes more conscious of using appropriate words and expressions in her mother-tongue.

How has the language changed inter-generationally? Liziwe has noticed that there are words that she uses when speaking to her mother and different ones she uses with her child, even though addressing the same issues. She has noticed a huge shift in vocabulary and her children do not know the isiXhosa words for ‘flower’, ‘feather’ or even ‘toe’, which were considered basic knowledge in her upbringing. Her research found that verbs are being adopted from English, such as ‘swim-a’ for ‘swim’ and ‘walk-a’ for ‘walk’! This appears to be the case not only for Liziwe’s children, but also in general for the current generation of urban isiXhosa speaking children. She found grammatical simplification where her children utilize grammar closely resembling that of English language.

Why are there these changes? Liziwe postulates that the isiXhosa spoken by different generations is different because they want to use it to communicate and get things done and because there is a desire to accommodate the other, shifts from the standard version of the language occur.

Where to from here? Having embarked on this journey, Liziwe’s is eager to learn more and she is registered for a Masters where she is examining how adoptives (words taken from other languages) acquire different morphemes. Questions she is asking are, for example, why is it ‘u-pipe’ (pipe) but ‘i-drink’?

And how does Liziwe juggle work, parenting and studying? She says she creates a schedule where once she is home from work, she would sleep and then study for two to three hours at night. Her curiosity about life, people and the languages they speak is what drives this determined woman.