Posted on October 27, 2010

In February 2010, the City of Vancouver in Canada hosted the first major global sports event of 2010, the Winter Olympics. Between June and July South Africa hosted the next major global sports event, the 2010 FIFA World Cup. While there are numerous differences between the two events, the similarities are significant. Both events had huge bureaucracies in the form organising committees, the Vancouver organising committee popularly known as VanOC and South Africa's local organising committee popularly known as LOC. Additionally, both South Africa and Canada have similar, though not the same, spheres of government with Canada being federal, provincial and municipal and South Africa being national, provincial and municipal.

However, the differences between the sports events are important to note. Olympics have primarily been held within cities, meaning that while national governments have been intensely involved, it is the city that is ultimately one to deliver a good event. World Cup tournaments, on the other hand, are a national and sometimes even international event where two countries could co-host, such as the 2002 event in Korea and Japan.

Regardless of the structure, each of these events have specially constituted bureaucracies that are responsible to deliver a spectacle. These bureaucracies in the form of local organising committees generate extensive records as by-products of the process of preparing for and hosting the global spectacles. The question one would ask is, what happens to these records once the event is over?

In Vancouver, the responsibility of managing the records of the VanOC fell to the City of Vancouver Archives, which is a division within the City Clerk's office. As a result of this responsibility explicitly stated in the Host City Agreement, the City Archives put together a small team and a budget within its Digital Archives Project whose timeline started in November 2009 and ends in December 2010.

In South Africa, one would assume that similar plans have been put in place and based on national legislation, the responsibility of managing the records would fall to the National Archives and Records Service. However, based on how digital records have been managed in South Africa in the past, there is course for concern. For example, while the bulk of the records of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's (TRC) were in hard copy format, a substantial amount were digital. In 2004, Verne Harris published an article (which has subsequently been included as a chapter in his book) titled 'The Record, the Archive and Electronic Technologies in South Africa' (1). He outlines the alarming rate with which the nation's electronic memory is evaporating due to the web of interrelated complexities ranging from under-resourcing (which some may consider easy to address) to the powerful cultures of secrecy and intolerance inherited from the apartheid era (which require responses at a political level).

What lessons can we learn from the City of Vancouver? Firstly, the planning and budgeting for the digital archive system started some months before the event actually took place with a budget of about half a million US dollars.

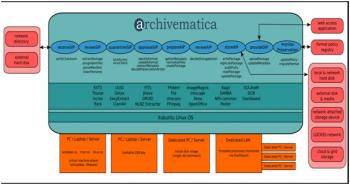

Secondly, the City of Vancouver (like the South Africa national government) promotes open standards and open source software. This means that the City Archives have had to include, in their strategy, open source tools. However, open standards and open source software does not mean less work. Processes such as integrity checking, file format identification and validation, meta data extraction and management, format migration to normalised preservation copies and access copies etc, will have to be done not by one software application but rather a family of applications. The diagram below is a graphical representation of workflow steps and preservation actions the tools are expected to process. (2)

Lastly, the City of Vancouver Archives team is collaborating with an international research project (InterPARES) that is looking at issues of long-term preservation and therefore able to draw on the expertise of researchers within the project as well as exchange ideas with other organisations undertaking similar tasks.

If South Africa is to manage the records of the 2010 World Cup, then preparations similar to those in Vancouver should have began in order to ensure that the documentary heritage of this once in a lifetime event remain available for generations to come.

Shadrack Katuu is a doctoral student at the University of South Africa and also serves as an international collaborator of the InterPARES 3 Project. http://www.interpares.org/ip3/ip3_itl_partners.cfm

Notes

(1) See Verne Harris (2007) Archives and Justice: A South African Perspective Society of American Archivists; Chicago pg. 157-170

(2) For more information on the workflow processes see http://archivematica.org