Posted on August 10, 2010

Many people think that the second enclosure movement actually started with the rise of the information economy - the birth of the Internet. But, of course, this form of commons enclosure had already been taking place within mass media itself. A closer look at news and entertainment media will reveal that a very small number of holding companies around the globe actually owned a variety of media and that smaller entrepreneurs were effectively bought out or edged out in monopolist maneuvers. From this perspective, it is no surprise that four corporations control about 80% of global market share in the music industry. A closer look at the music industry itself reveals that a large number of contributors to the USA’s musical heritage do not actually own the rights to the music that they composed or performed. A similar picture emerges when one looks at narratives of injustice in South Africa - the most prominent example is that Solomon Linda's 'Mbube', which generated a substantial amount of revenue for American musicians and ended upon being used in Disney's motion picture, The Lion King. The not so funny punch line is that is that Solomon Linda did not die a rich man and that, until fairly recently, his family did not receive a share of the profits generated by the song. In short, the collaborative as well as often competitive culture within which African and African-American genres of mbaqanga, kwela, jazz, blues and soul were created often went on to generate revenue for corporate monopolies - often at the expense of the very composers, who either signed away the royalties in ignorance, or due to poor bargaining power. If the blues, for example, was grown in a musical commons, it certainly had been enclosed by the time Jimi Hendrix made it to Woodstock.

One genre of music that took its revenge upon this history of often racial injustice was hip-hop. It was black nationalist hip-hop that not only delivered incendiary political messages, but also sampled a wide range of music and media. Often much of the music that they sampled was composed or recorded by black musicians. The only catch is that many of these musicians did not own the rights to their music - this is hardly surprising, given that the black liberation struggle was still in the making during the mid-twentieth century. Instead, this music sat in the back catalogues of major labels, either to be forgotten or to be pulled out for Christmas compilations (if the songs fitted the bill) or to be used by newer generations of commercial singers that were signed to those major labels. Hip-hop producers and DJs thus acted as alternative historiographers digging up forgotten artifacts of black cultural history. You might say that these artists had liberated forgotten black cultural expression from back catalogues and placed them back into the public domain or knowledge commons. Of course, the rights holders over these works did not see it in the same way and legal threats and law suits ensued. The most notable law suit was Campbell v Acuff-Rose, in which 2Live Crew was sued for referencing Roy Orbison's 'Pretty Woman' - of course, Orbison was not a black musician, but the crew's parody of this rocker's work was not unlike Public Enemy's explicit disrespect for figures, like Elvis Presley and John Wayne, both of whom are framed as patriotic icons of a proud [white] 'American century'. Much to the annoyance of the music industry, the courts found in favour of the rappers. It held that parody of a copyrighted work was fair use. In US law, fair use exceptions to copyright allow creators to use other creators' work without obtaining their permission.

Despite this victory, hip-hop sampling became less and less ambitious because the process of defending a law suit is rather expensive and time-consuming. Thus the potential of expanding the knowledge commons (even by commercial rappers) was beginning to shrink. That is, until the mp3 revolution and peer-to-peer platforms took Hollywood's fear of hip-hop sampling in recording studios to every person who had a computer (or mobile device) in their home, office, school or anywhere you can imagine. Thus, whilst the door seemed to be closing on subversive versions of hip-hop, technology was now opening up new doors for a wider variety of people, even if they were on the wrong side of the digital divide. That said, the hip-hop's political significance certainly has not passed its 'sell by' date in a wide range of places outside of the USA, be it Brazil, South Africa, Senegal, Egypt, or New Zealand. If you tune in to Xhosa and Afrikaans rappers from Cape Town, for example, you will find a great deal of creative and politically subversive use of sampling and musical approaches that hip-hop has mutated well beyond the confines of the mainstream American music industry. In fact, politically conscious hip-hop has been alive in Cape Town for over twenty years and yet you may be find it difficult to locate the history of black urban culture in local archives or a museum, except in the form of academic journal articles or a handful of academic books at university libraries. One individual, Shamiel Adams (aka DJ Shamiel X), has attempted to correct this by launching the Museum of Hip-Hop in South Africa, which offered an exhibition of Cape Town's hip-hop history and created a performance and workshop space hip-hop heads outside of commercial spaces, like night clubs or commercial radio promotions. Sadly, the museum vacated its expensive Cape Town CBD location in mid-2010 and is looking for new premises. The pressures of sustaining an initiative that requires a physical space is great. Whilst many would argue that an online archive would be the best approach, Adams contends that young township youth need safe, non-threatening and not entirely commercial spaces where they can meet, learn, play, compete and debate. In certain respects, Black Noise's Emile Jansen creates such spaces on a periodic basis via workshops and annual competitions, like Hip-Hop Indaba and African Battle Cry. Of course, these events do not offer a permanent space where knowledge and art works can be archived for posterity. The question at stake with Adams's desire for a museum or archive of Cape urban youth culture is the question of who mediates cultural expression and cultural history. Who is entitled to own the knowledge repository black urban culture? Government? Do we leave it to alcohol marketers to fly 90s commercial rappers Vanilla Ice or MC Hammer to South Africa to star in beer adverts? Are knowledge repositories the exclusive domain of academic institutions? Do we allow corporate monopolies to mediate our past on our behalf, or do we collaborate to build a knowledge commons that both reflects and shapes our past and future?

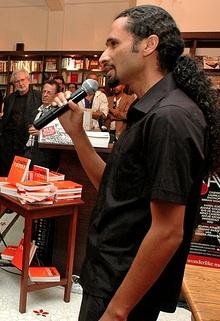

Dr. Adam Haupt is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Film & Media Studies, University of Cape Town. He is the author of Stealing Empire: p2p, intellectual property and hip-hop subversion (HSRC Press, 2008) and is a Spring 2010 Mandela Mellon Fellow at Harvard University's Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research.