Posted on October 24, 2013

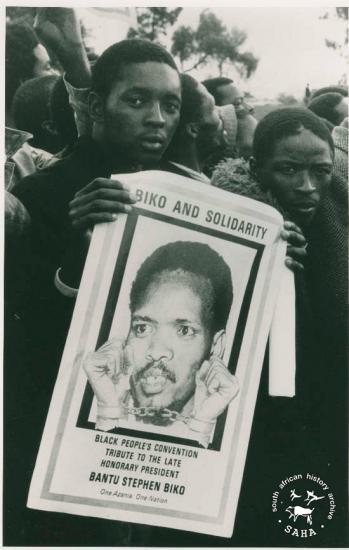

I cannot say who hid the poster there as I never bothered to ask, but somehow I knew that the image was somewhat forbidden. This was of course in 1980s South Africa, the streets were on fire and our schooling was occasionally disrupted by the unrest. As young as I was at the time, I knew that I could not mention my discovery to anyone, even my own cousins who frequented our household. I do not even think I could even read , nor understand the message: 'Tribute to the late honorary president Bantu Stephen Biko' - this could be partly a result of the Bantu Education I was being fed at the time but still the poster haunted me.

Even with the hauntedness that came with my daily pilgrimage to the secret spot behind the room divider, I still visited the spot every single day. The pilgrimage itself was in the form of making sure that there wasn't anyone inside the house, I could not even risk having someone in the other room as this was a typical four-roomed matchbox that was typical of apartheid architecture. When I was sure that there was no risk of anyone walking into the house, I would quickly reach behind the room-divider without even looking and the feel about for the cardboard that the poster was pasted on. I would pull it out and gaze at the image of Biko for a long while.

I cannot say what went through my mind as I was gazing at the poster but I do recall paying special attention to the superimposed hands that were symbolically breaking the chains. I knew these hands did not belong to Biko as they did not look like they belonged to face that I spent days and hours studying. Not once did I doubt that the man whose face was staring back at me symbolised our condition at the time. The chains, I knew very well that they symbolised the will to break away the chains of bondage.

Today as we commemorate the death of Steve Biko I found myself thinking back to that poster and wondered what happened to it. My grandmother moved from that tinny matchbox around 1987, I also left for boarding school and I doubt that anyone felt the need to save the poster during the move. Thanks to modern technology, I decided to Google the poster, using the keywords: 'Biko Funeral Poster' and voila! My best kept childhood secret was suddenly there, staring back at me on my computer screen, thanks to the South African History Archive (SAHA) website. This brought back a flood of bitter sweet memories of my childhood - my grandmother's matchbox, the room divider, the anxiety I felt when I reached behind it, the fire on the streets of Mdantsan.

Not only was I nostalgic but I found a new appreciation for archives but even more so, for modern technology and the opportunities that digitisation provides for the preservation of archival material. Not only was I reunited with a poster that was my imaginary friend of sorts, but with a fragment from my childhood that helped shape my thinking and sense of self. Through my youth, I was drawn to Steve Biko, I started reading his writing and remember clearly the first time I bought my own copy of the collection of his essays; I write what I like.

By the time I reached adulthood, I had a private sense of homeboy adoration for the man and tried my best to uphold his notion of black consciousness in private and also publicly. From the way I raise my children to how I maintain my hair - the ideological underpinnings of it all are still influenced by Biko. Staring back into this image today, I cannot help but feel haunted, even in the present; haunted by how everything that Biko stood and died for has not yet been realised. No, actually I lie; there is a lot that is different: I can now look at this poster today and it is available on the World Wide Web for all to see. It is no longer risky to keep it or look at it. I can also share it publicly, without the fear of getting arrested. For a moment I feel like it does not even matter who hid the poster behind the room divider, what matters to me now is that it helped shape me into the person I am today.

Xolelwa Kashe-Katiya is an Archival Platform Correspondent