Posted on September 18, 2012

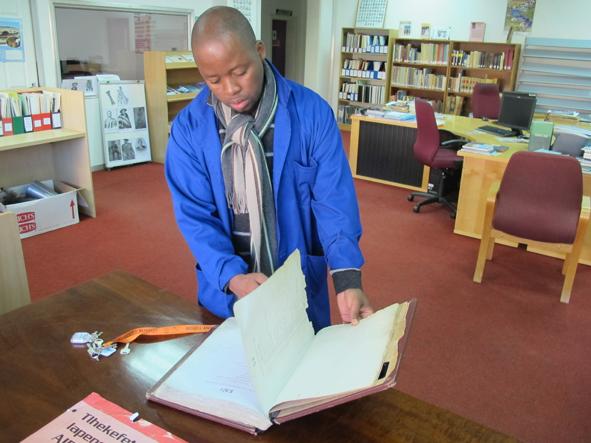

Sebinane Lekoekoe in the reading room of Lesotho's National Archives.Photograph credit: Jo-Anne Duggan

It has been a buzzword and chorus almost globally that archives play a critical role in administrative transparency and democratic accountability, however these positive feedback loops are hindered by lack of improved public understanding of archives. Archivists are faced with a huge challenge of raising awareness of the importance of archives. As a result this handicaps proper collecting, identifying and preserving documents of historical value before they get lost.

Pillars of ensuring survival for posterity of this documentary heritage include standard legislative frameworks, infrastructure, as well as organisational and staffing structures, among others. Archives are components of historical and cultural heritage and their essence lies in their evidential value. It is in this understanding that archives are referred to as the 'nation's memory bank'. The International Council on Archives defines archives as 'sources of the identity and memory of nations, societies and individuals which allow peoples and successive generations to understand their history. They also enable citizens to exercise their right to information and are thus a cornerstone of the information society and the democratic process.'

Established in 1958 in the then Basutoland Authorities, the Lesotho State Archives has been housed under various government departments, including the Office of the General Secretary of the Department of Information in the Ministry of Education until 2006, when it was placed under the Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Culture as an independent department of Library and Archives. On paper, its mission, objectives and responsibilities are of world-class. If all the sweet verses were practical, Lesotho would not be counted among countries whose treasure house of information would easily be destroyed, as was the case a few weeks back where a registry in the Ministry of Public Service housing important government records went up in flames.

The archaic Lesotho Archives Act (of 1967) defines archives as 'any documents or records received or created in a government office or office of a public authority during the conduct of affairs in that office and which are from their nature or in terms of any other law not required to be dealt with otherwise...' In this regard, records are considered archives from their very early stage of creation and this implies they carry an immense value, hence why all necessary measures should be put in place regarding their safety. If the mandate of the institution was not a romance on paper, our State Archives would not be characterised by deteriorating archival services.

Lesotho is still lagging behind in terms of archival management, practice and policy. The legislation is important in that it enables any organisation to operate with authority. The Lesotho Archives Act, as old as it is, however, advocates for establishment of other essential structures which are not in place even since the adoption of the act. These include, among others, an overseer of the records and archival services at national level (Chief Archivist). Among his or her roles would be 'inspection of archives, taking charge of custody, care and control of archives'.

Another essential consideration advocated for by the act is the establishment of an Archives Commission (currently not existing) that would be tasked with making recommendations regarding the acquisition of documents and records and disposal of archives, and make recommendations on all matters relating to archives. This would play an advisory role regarding proper archives and records management.

This legal framework has a handful of loopholes that also loosen the value of this national asset, as among others, it still follows the old style where access to records is after thirty years. It is also quit about copyright, among other critical issues. More importantly, it only imposes a petty fine not exceeding R200 or imprisonment of less than a year against a person who damages any archives treasure. Another complete silence is also on the issue of digitisation, which is a preservation tool, whose importance in the preservation and conservation of archival heritage is tremendous. Therefore, not even a policy on digitisation looks possible in the near future. Let me point out that Lesotho State Archives has in custody tons of records with some dating back as far as 1884! And all these are paper based.

Lesotho is no exception in lack of clear understanding of the importance of the records. As a result, the national archival system is neglected and the necessary structures pertaining to the safety and preservation of this national asset are inexistent. There has been an outcry for decades now for the establishment of a record centre that plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of a record as it would be a home for semi-current records. This would curb the dumping of records in the dark rooms as at times this is owing to shortage of space in the registries.

Inasmuch as the legislation states archives to be records at creation level, there is no clear relationship between the State Archives and registries and they both operate in different worlds. The legislation does not give the national archival administration wide powers for protecting records as it does not enable the State Archives to be actively involved in all phases of the record life cycle. At one point the State Archives established a committee of registry personnel in order to link their institutions with the State Archives, but this seems not to be fully operational.

It has become the work of the archivists to hunt from not only registries but also government offices for records on regular records surveys and audits. This exercise is paralysed by shortage of staff at the State Archives as it has only five people in all, who all face a challenge of relevant training. This means there is a huge backlog as there are too many registries (currently twenty-four government ministries). This has for years been carried out with assistance of part-time employees and this is no more the case. As a result there are too many records piling up in both registries and government offices.

However, some of the ministries, aware of the duress facing the State archives, on a regular basis organise for part-time employees (on their own budget) to clean their records before the State Archives staff groom them. Currently the State Archives repository is housing temporary staff engaged by the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs as a way of easing the weight on the State Archives personnel. (Not to talk of the impact on records when the archives repository is now a working room, with lights on all day long!). One other development by the Ministry of Finance is establishment of the Ministerial records centre, aware of the duress on the State Archives in handling records from all directions.

If it would register on governments that Archives inform public deliberation about identity and citizenship, a way forward would be mapped to preserve this wealth. Aware of the existing gaps, last year, a team from State Archives made efforts to preserve the traces of memory of indigenous people to supplement the documentary material held by State Archives. This is where they documented biographies of Principal Chiefs with the view that chieftainship is the backbone of the Lesotho's bureaucratic system. Planned for this year was a project to capture memories of World War II veterans in order to include their voices and experiences in the national literature.

Access is of paramount essence to any archival institution, otherwise there would be no reason why archival institutions should be in existence. However, if proper measures are not put in place, and there is still this absence of effective lines of communication and coordination , records will sit in dark filthy storage rooms and it is here where they become obsolete and the state faces a risk of losing historical memory or too many essential records may take ages before being accessible, if by luck they do ever become accessible.

Another important tool to ease access is a catalogue to direct one on the holdings of the institution. The one at the Lesotho State Archives is only of colonial records, which is also not genuine at times as some of the records indicated to be held by the institution do not exist within the collection. Access is also hindered by dispersed archives around the world and no remedial efforts are in place for this as the legislation fails to protect such archives also fails to provide arrangements for the return of Lesotho documents which have been expatriated in various ways.

Owing to budget constraints another challenge is still to publicise the importance of records through being part of the global community in celebrating international days meant to mark and raise awareness on the importance of archives. In this way, no better understanding of the archival heritage is instilled in the public to develop a different eye on the importance of the archive.

It is high time, if we do not want to culturally impoverish coming generations, that this wealth be taken seriously through enabling them access the traces of their past. Legislation should be developed that directs a relationship between the agencies that create the records and the archival institution, legislation that covers current developments in the field of cultural property. The state archives should be accorded the necessary dignity through better human resources and a relevant human resource grading system, and initial advisory bodies on proper records and archives management should be re-established. The mentality that archives are boring, irrelevant, dirty piles of papers that document the doings of the colonisers should be revised.

Sebinane Lekoekoe is an Archival Platform correspondent based in Lesotho