Posted on August 10, 2010

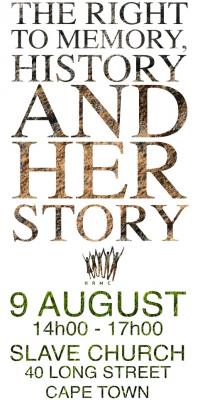

The right to memory appears increasingly in popular usage - see invitation on the left - and in the literature on human rights, social justice, history, the archive and the right to truth. The question is, if memory matters, should the right to it be defined and protected, and if so, how and by whom?

In search of some answers to these questions I looked first at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The right to memory is not among the many listed, although it could be argued that the exercise of several human rights or fundamental freedoms is contingent on memory. Freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 18), freedom of opinion, expression and the right to seek, receive and impart information (Article 19), freedom to participate in the cultural life of the community (Article 27) are surely not possible without free access to the collective memory. Conversely, maybe these freedoms guarantee the right to memory.

Searching through documents dealing with memory, I was fascinated to find mention of various 'memory laws'. Is it really possible to legislate for memory? In France four memory laws were enacted between 1990 and 2005. These criminalise the denial of the Holocaust of European Jews; recognise slavery as a crime against humanity; highlight the positive role that France played in her former colonies and; acknowledge the Armenian Massacre of 1915. These laws don't determine what is remembered or what is forgotten; they sanction a version of the past or prescribe an attitude to it and they make provision for anyone who holds an alternative view to be fined or imprisoned. Surely these laws abuse the rights to freedom of thought, conscience, expression and opinion, not to say the freedom to seek, receive and impart information? It's absurd to imagine that one can legislate memory in order to wish away the past or reframe it for political ends.

Absurd or not, the Russians tried the same tactic. Not content with rewriting history textbooks to portray Stalinism in a more positive light and confiscating an entire archive dealing with repression to render evidence that supported an opposing viewpoint inaccessible, they also tried to enact a law to criminalise a particular version of the past. Why? Because they wanted to protect the Soviet viewpoint on the events of the war from revisionist interpretations or, as the lawmakers said, to put an end to "efforts to falsify history contrary to the interest of the Russian Federation". Did they really think it was possible to stem the tide of historical memory? Surely the imposition of a state-sanctioned version of historical events, coupled with actions that impede access to historical archives, is an abuse of the right to memory, as well as to the rights of freedom of opinion, thought and expression?

Hundreds of thousands of people suffered during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and under the forty year dictatorship of General Franco that followed it. In 2007 the Spanish government passed a 'Law of Historical Memory', ending the 'pact of silence' that had endured for thirty years. This law acknowledged those who suffered persecution or violence for political, ideological or religious reasons and law decreed, amongst other things, that local government should help locate, exhume from mass graves and identify the bodies of victims. It seemed that there was a willingness to open up the archive, not just the physical records, but also the memory and places that tell the stories of the country's history, to elucidate the past. Those in favour of the law described it as long overdue. Opponents warned that it would open up old wounds and prejudice national harmony. An attempt, in 2008, to access information, with a view to possibly prosecuting the perpetrators, was suspended on the grounds that it contravened an earlier amnesty. Is it enough to acknowledge the collective memory? Is the right to seek, receive and impart information enough? Is finding 'the truth' enough? Don't these need to be coupled with justice in some way or another?

Several African and South America countries have established judicial and other processes to deal with the legacy of atrocities and the abuse of human rights. These commissions seek broadly to document human rights violations and make recommendations regarding reparations. The commissions rely on memory, particularly where the records of government have been destroyed. They all seek to arrive at 'the truth' and to attain justice by accessing memory. Memory is important because it can register a historical injustice or a subaltern concern that might otherwise be missed.

One outcome of these commissions has been the establishment of museums and archives that honour the victims, house and preserve the records and the memory of atrocities and the truth seeking processes. While some are of the opinion that these "consolidate a democratic culture" others suggest quite cynically that "it's a struggle over who gets to write history". There are strong imperatives to draw on memory to find the truth about what happened in the past, not least of all so as to achieve justice. But, memory and truth are not necessarily infallible or cast in stone, both are open to manipulation. The processes through which choices are made about which memories to record and preserve and the way in which these memories are used to justify a particular version of history, made publicly accessible or hidden from view are not neutral. They are always governed by one agenda or another.

It's not appropriate for legislation to protect a particular version of the past, any one history, memory or truth. It's possible for legislation to protect the resources on which ongoing memory, and truth processes rely: the archive. It's necessary to have the resources on hand to argue for or against a particular version of the past. It's critical to ensure that the information required for the exercise of human rights is preserved. It's essential to strengthen and make accessible an archive that extends beyond the formal record of government to include the records of non-governmental organisations, personal papers and anything else that carries memory.

That's why the Archival Platform considers it important to draw your attention to projects like Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action(GALA), AmaLwandle and the Human Rights Media Centre amongst others. The projects are run by people who mobilise their energies, throw their hearts and minds into the work of giving substance to the right to memory and in the process make an invaluable contribution to extending the archive.

In conclusion, Ariel Dorfman reminds us that, "Memory matters. One of the primary reasons behind the extraordinary crisis humanity finds itself in is due to the exclusion of billions of human beings and what they remember, men and women who are not even a faraway flicker on our nightly news, on the screen of reality." Ariel Dorman, Whose memory? Whose justice? A meditation on how and when and if to reconcile, 8th Mandela Lecture, 31 July 2010

Jo-Anne Duggan

August 2010