Posted on May 11, 2010

Much has been written about the nature and form of memorialisation - public memorials, museums or commemorative activities, or sites of conscience - and the challenges of balancing multiple perspectives and polarised views, of balancing the didactic imperative with the need to provide places of reflection and symbolic reparation, of making decisions about who, how and where to remember, and for what purpose. And many museums have been created to house the relics of atrocities, even, in some instances, the remains of the victims. But what is of particular interest to me is the use to which records - written, visual and audio - are put in the process of memorialisation, and the ways in which these records, that might once have been held safe in the archive are presented, through exhibitions, as powerful and evocative evidence of the past.

Drawing on a vast collection of documentary material donated by individuals, organisations and institutions, exhibitions tell the story of the efforts of governments and victim's organisations to establish the truth about the violations, to find the 'disappeared', to obtain justice and to provide reparation for victims. Displays include letters and drawings from children to their imprisoned parents, filmed testimony of human rights violations, press clippings, legal documents, posters, clandestine publications and previously unseen film footage.

In putting together the Museum's collection, the Chilean government joined forces with Corporacian Casa de la Memoria (House of Memory Corporation), which includes three human rights groups: the Corporation for the Promotion and Defence of People's Rights (CODEPU), the Social Aid Foundation of Christian Churches (FASIC), and the Programme for the Support of Children Hurt by States of Emergency (PIDEE), and an audiovisual production company Nueva Imagen (formerly Teleanalisis). In 2003, the historical archives of these four organisations, together with the documents of the Chilean Human Rights Commission, the Group of Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared (AFDD), the Justice and Democracy Corporation, and the Solidarity Vicariate Archives Foundation, were incorporated by UNESCO in the Memory of the World Register.

The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute based in Yervan, Armenia, documents and presents material relating to the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1922. Exhibits in the Museum draw on a range of archival material including eyewitness reports, photographs, film footage and documents issued by organisations and foreign governments condemning the genocide. The Institute focuses on collectiing and researching historical-documentary materials, archived documents, photographic documentation and the accumulating of new data, including eye-witness accounts of Genocide.

The compilation and curaton of this archive is particularly important in the context of the wider debate about the Armenian genocide - which the Turkish government has long denied - and the restrictions on access to relevant material in the Turkish archives.

The Iraq Memory Foundation, an organisation based in Baghdad and Washington, documents the institutions of repression and social control that dominated all aspects of Iraqi life between 1968 and 2003. The Foundation collects, digitises and classifies documents relating to the years of terror and films and archives individual stories of survivors and witnesses to the atrocity. The holdings of the Foundation include the record of reports and correspondence from the ruling party of the time as well as documents from individuals or organisations.

While material in the archival collection is intended to form the basis for exhibitions in the museum, still at the planning stage, the Foundation, recognising the potency of information it contains, notes that, 'We, at the Iraq Memory Foundation, believe that the culture of secrecy, surveillance, and unbound state control of information exercised by the Saddam Hussein regime, has to be replaced in the new Iraq by an approach that balances the legitimate needs of state agencies for confidential information against the fundamental premise of freedom of information bound only by respect for the privacy of individuals.'Â While stating their commitment to facilitating public access to the records, the Foundation has expressed concern that the unmitigated release of material may cause harm to individuals and society. In support of this argument they cite records which include: descriptions of gratuitous violence; those that contain the names of individuals who served as informer and against whom acts of revenge may be exacted; names of public figures who may be called to account for the actions of the previous regime: and records which detail acts of tribal conflict, which could prove inflammatory in an already volatile society.

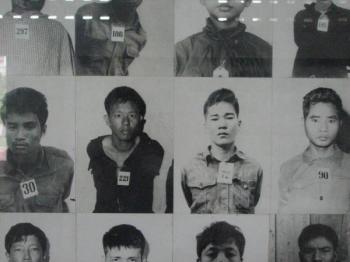

This archive constitutes an almost complete documentary record of the prison system, a fundamental instrument of a regime under which 2-3 million people lost their lives between 1975 and 1979. The Tuol Sleng archive, as an important repository of historical materials of the Democratic Kampuchea period, has been central to historical analysis and memory-work in the post-1979 period. Material from this collection, including some of the more than 6,000 portraits of detainees, has been exhibited in museums around the world.

The Kigali Memorial Centre, like many similar institutions does not rely on the public record, but builds its archives through engagement with survivors and those who observed the conflict. And, importantly, retains the record on site shifting custodianship away from centralised repositories.

Reflecting on these museums, one is reminded of the power of the archive as the record of what has been seen, said, written and done, and as artefact, an often fragile fragment that has survived as a potent force through which we can remember the past, engage with the present and imagine the future.

Jo-Anne Duggan is the Director of the Archival Platform

Kigali Memory Centre