Posted on November 21, 2010

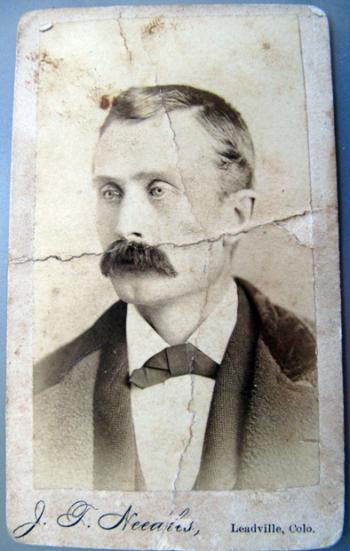

This is the pathway of one family over the past 169 years. It appears that William Cogeen and Martha Jennings travelled separately to Colorado. William was a miner, born on the Isle of Man, in a place called Laxey Glen, who joined the mining rush in Denver. Or was it Leadville that he went to? He appears in the census of 1861, aged 9, and then disappears. He reappears in a photograph taken in a studio in Leadville, CO a few years later. He and Martha had two daughters in the US. They appear to then have moved back to Cornwall before the mineral rush brought them to Johannesburg. Martha seems to have been a domestic worker who joined her brother going to work on the mines in the United States. Perhaps she left Cornwall in order to escape the dead end that her life seemed to be headed towards.

Vivien Horler, William and Martha's great-granddaughter and assistant editor of the Weekend Argus in Cape Town, is in the painstaking process of constructing a narrative out of the bits and pieces of information her research keeps throwing up. She has been tracing one branch of her family, the branch that is responsible for the family's constant movement between South Africa and England in the last three four generations. Over the years she has searched for names in the British census records. That is how she has traced William back to 1851. She has also followed the clues on old photographs that she has in her possession of members of her family. Most of these portraits carry the names and addresses of the studios where they were taken. That is how Vivien came to find out that William and Martha had lived in Leadville rather than Denver where her grandmother had always said she was born. Of course, Vivien's grandmother may well have been born in Denver. What Vivien has established from contacting a local newspaper in Leadville, which referred her to a genealogist who works for the local library, was that her family does indeed appear on the census as having lived at a particular address in Leadville.

Vivien's grandmother married a Cornish man whom she met in Johannesburg. They relocated to Cornwall and so Vivien's mother was born in England as was Vivien. When her grandfather was called up for conscription during World War II, he asked for time to go and tie up his family's business in Johannesburg where they owned several small properties in Malvern and Denver. He stayed away until after the end of the war. Subsequently her grandparents decided to return to South Africa to spend part of the year here. They were never to leave again. Vivien came out to South Africa with her mother and her aunt when she was 2 years old. The plenty that they found in comparison to the rationing of almost everything in England after the war made her mother appeal to her father to join them in South Africa. And so he did. As a result, home is more than one place for the family. Says Vivien, “Every time you go back and see England you think, ‘It's very nice, but I wouldn't want to stay'. It's crowded and small, life is harder there. It's more difficult to get around, everywhere you go six people got there before you. Everything is small, even the showers.â€Â

Parts of the story remain hazy. Gaps in factual information can only be filled through speculation at this point. When Vivien gets to writing up this information she will use fictional narrative where she cannot know what transpired in the lives of her forebears. She is passionate about the project and keeps going despite the frustration she encounters sometimes when her labour yields no useful information. She also says, "It's so nice when somebody is interested. Usually they same, 'Oh gosh, there she is, going banging on about the family'"Â when I ask about interest in her work in her family.

I leave our conversation with a changing sense of the South African past. I've only ever heard a faint suggestion of this kind of migration to South Africa during the mineral rush of the late 19th century in the literature I have read before.

Mbongiseni Buthelezi is the Archival Platform's Ancestral Stories Coordinator