Posted on December 14, 2011

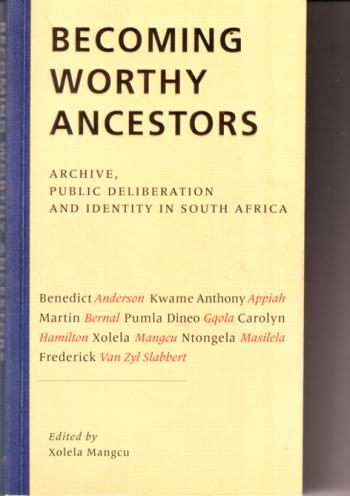

Yet now public discussions concerning identity in post-apartheid South Africa seem to be dominated by explaining, in very strict terms, what it means to be an authentic African. And like the true outcomes-based educated thinkers we seem to have become, we are concerned with providing an answer to this question without seeming to realise that the fact that the question necessitates a single answer instead of allowing for more than one right answer, means that we're recycling the very problem we're trying to solve. Furthermore, we don't notice that the very asking of a question of this kind is a symptom of an intellectual suffering, a malaise that we, the darling country of the continent, should not be nursing. The essays in Becoming Worthy Ancestors attempt to explain and respond to the malaise of authentic Africanness by highlighting how the archive's ambiguous ability to include or marginalise certain identities means that its strongest feature as a critical tool is its ability to problematise. It is this feature which enables us to use the archive to question simultaneously the identities we are resisting and those we are affirming, in order to help us realise that our identity as a (new) nation is constantly in transition.

In his opening essay, "Evidentiary Genocide: Intersections of Race, Power and the Archive", Xolela Mangcu highlights how the archive can take on an oppressive quality by privileging the histories of certain identities over others by demonstrating how the ANC appropriated the language of the Black Consciousness and Pan Africanist movements, while vilifying the role these movements played in the liberation struggle. An example of this distortion can be seen by Julius, saying that the march on Sharpeville of 1960 was organised by the ANC and not the PAC.

Mangcu further argues that the ANC, under former president Thabo Mbeki, represented black consciousness as a nativist movement which was a misreading of Biko's formulation of blackness as a political and historical condition rather than a biological one. He reads this appropriation and distortion as a sign of the ANC's insistence that history be viewed through its own lens. He goes further and implicates the media's collusion in providing the ANC struggle effort over all others by representing the ANC as non-racial and the other movements as racist. He later argues that the media conveniently forgot that the ANC only started opening up membership to whites in 1969 and leadership positions to whites in 1985. He points to the contradictory reactions of white South Africans who loved Mandela but seemed to recoil and hate the renaming of Johannesburg international airport to O. R. Tambo International. He maintains that the reason for the resistance from white quarters was that Oliver Tambo was represented by the media as an '80s terrorist and Mandela as the saint who absolved them of any responsibility.

There is a similar tense awareness running through all the essays. Martin Bernal's essay, "Africa in Europe, Egypt in Greece"Â, offers linguistic evidence of Africa's contribution to Greek civilisation. He argues that almost half of the Greek vocabulary is of Egyptian origin and therefore proves that Africa was the source of European civilisation. What's interesting is that Bernal refuses to be designated as a defender of a particular stable position; he refuses appropriation by purists who claim that civilisation came out of Africa and he refuses criticism by those who claim civilisation did not originate from Africa.

In her essay Carolyn Hamilton speaks of the destabilisation of authority as one of the first steps that enables deliberation around identity. She comments on the lack of interest in history in public life and the growing desire to engage in questions of the past through literature which "reaches into the archive for its stories and sometimes comes to occupy the space of archive, though less with the purpose of establishing truths about the past and orientated rather, towards the idea of multiple truths"Â (136). This comment is one that can be read as doing two things. Firstly she highlights the ambiguous nature of the archive and secondly she asserts that the current intellectual climate's experience of the archive is of suppressed identity and public debate. She later writes that "archive once produces and destabilizes nation, and the challenge to the worthy ancestor is to proceed in knowledge of the power of the archive"Â(138).

In her chapter Pumla Dineo Gqola similarly points to male-centred readings of female struggle heroes and argues that the fact that many think there are no black female intellectuals in the public sphere as a matter which necessitates a rethinking of the authority ceded to the historical archive and terms of the public debate around intellectual women as it now stands. She argues that black female intellectuals do exist, but their contributions can best be understood by resisting interpretations of women as appendages to men in the history of the struggle.

The late Van Zyl Slabbert in his essay, "Some Do Contest the Assertion That I Am an African"Â, argues for a similar awareness in the logic we use to decide inclusion into the authentic African group. He argues against dogmatic, closed systems of knowledge that assert that their truth is the only truth and therefore that it is the right truth. His argument that using falsifiable concepts opens up space for meaningful engagements concerning important issues like our inherited history and race gets to the heart of the ambiguous role of the archive. Let me explain.

All the essayists included in Becoming Worthy Ancestors are involved in resisting some identity claim that has gained its authority by referring to the information that has either been included or excluded in the archive. Their resistance is not one that seeks to make a positive assertion of their truth, rather it is one that understands that our present context, as an adolescent nation, requires that we critically test any assertions and denials concerning what it means to be South African. The archive plays a critical role in allowing us to do this because, as I said in the introduction, it problematises and by doing so it produces tension and ensures that our discussions on identity will fluctuate and change, just like us.

Busi Mnguni is an Honours student in the Department of English at the University of Cape Town.