Posted on March 12, 2013

Love can be an overwhelming feeling. I can think of only a few words that expresses this emotion. As African American singer and songwriter Shirley Bassey sings, "I'd like to run away from you, but if you never found me I would die; I'd like to break the chains you put around me but I know I never willâ€Â. In two sentences she alludes to a threat, death and enslavement. As complicated as it is, most of us fall ‘madly' in love. Usually obsession and fatal attraction are the warning signs that this kind of love can be the cause of a range of feelings and behaviours, like jealousy, pain, stress, selfishness, power struggles, guilt, and even suicide. Many people will testify that love conquers all. Even the Bible attests to this: "That which God has put together let no man put asunder until death do us part".

I would really like to see how it can work in our society today when we are struck on the love that fairy tales are made of. This kind of love is fed by notions of cultural and religious beliefs that blind us to who we are, where we come from, who and how we should love. This has smothered the true natural side of our humanity and freedom to just loving someone.

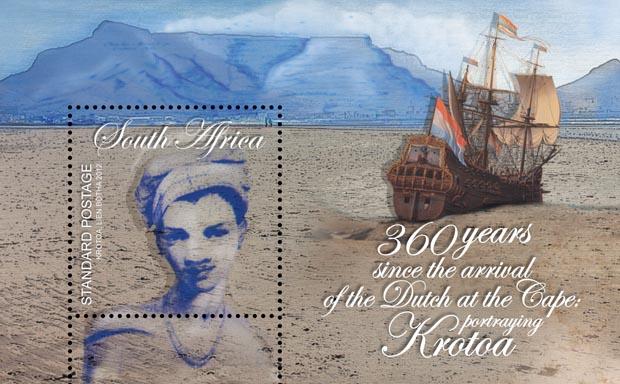

One extraordinary woman who is the subject of my story reveals a remarkable spirit that transcended the odds against her in 1600s Cape Town, South Africa. It is with great respect and admiration that I chose as my Valentine Krotoa 'Eva', birth mother of generations of South Africans, White, Black, Indian, etc. Her journey and short life sometime mirrors my own contemporary challenges as a woman and as lesbian, that of being judged. She is the first Khoe woman to appear in the European records of early settlement at the Cape. Many of us have not yet made an association with her because of reasons that might sometimes be out of our hands. Contributing challenges are lack of access to information and skewed historical interpretations of her life. In many respects one of the major causes of her tragedy was her love and marriage to European surgeon Pieter Van Meerhof in 1666.

Krotoa "˜Eva' van Meerhof becomes my tragic heroine. She, in her own right, actively opposed the takeover plans the Europeans were making in the early 1600s at the Cape. "She was a remarkable woman who, in six or seven years, had bridged the divide between Europe and Africa and as some people have attested to, became a symbol of what the new country could become". I might not agree as it becomes ironic later when the expansionists coerce indigenous labour and invade more and more of their land (Krotoa 'Eva' van de Kaap, SM/PROG [c. 1641 - 1674]; www.geni.com/Surnames/, van de Kaap Genealogy and van de Kaap Family History).

Their love becomes the first ever inter-cultural, interracial marriage ever in the history of Cape Town, South Africa. I believe this would undeniably become the cause of her tragedy. V. C Malherbe notes that Krotoa "pioneered hazardous terrain, namely the frontier between the Cape's Khoekhoe herders and premier European trading mercantile giants, the Dutch"Â. Yet we know that the journey leading up to her death had much to do with her identity as a newly christened Dutch-speaking indigene. She got trapped into Van Riebeeck's household at the tender age of seven and was later coerced into the dealings of the powerful colonial masters at the start of the expansionist era at the Cape. This meant her changing her ways of engagement both socially and culturally. It is said that she dressed in both her Indigenous attire and later got into her western clothes when she came back to Van Riebeeck's fort. (Malherbe, 1990: p. 62 ).

Kratoa came from a complex extended family of Khoe intelligentsia: she was the niece of Autshumato who was leader of an independent Goringhaicona group. They became interpreters stolen from Cape Town and taken by the British to Batavia to teach them English and provide training in the English ways. They became multi-linguists, had political shrewdness and were people who had travelled and experienced different cultures. Krotoa had a sister who had been married first to Goeboe, the Chainoqua chief, and later married Chief Oedasoa of the Cochoqua at the Cape. These individuals' stories remain footnotes obscured from public discussion.

Furthermore, Krotoa became the first indigene South African to be baptised a Christian, and Van Riebeeck named her 'Eva'. It becomes evident that her role as KhoeKhoe interpreter, linguist and later strategist and negotiator for both the Dutch and her Goringhaicona people, which included contact with other indigene groups, became a liability to both the Europeans and the Khoe at the Cape. Later in her life the bridge that she was aspiring to build was not required by the Dutch as they had their sights set on invading indigene terrain, which she realised too late.

Falling in love with and marrying Pieter van Meerhof was fraught with complications, leading her to live a double life. In one extract it is recorded that the van Meerhofs were an embarrassment at the fort (Castle), so the Dutch sent Pieter to work on Robben Island. A year after their marriage he left on a slave-trading expedition to Mauritius and Madagascar but later died in a skirmish. I ask the question why he had to leave his wife with their children when he knew she was not coping. Was he running away from his responsibilities? The mistrust between her, the Europeans and her own people centred on the fact that the 1650s onwards saw the gradual colonial takeover of her own people's land and forcing the Europeans' will onto them. As her familiarity with the settlers further complicated her existence, she ended up following a dissolute lifestyle, which brought her into disrepute with the Dutch community and resulted in her losing custody of her children. Her love for van Meerhof eventually killed her.

At the age of thirty three Krotoa 'Eva' died of a broken heart, a prisoner on Robben Island. This is what was said by Dutch diarist on her death: "This day departed this life, a certain female Hotentoo, named "˜Eva', on the 29 July 1674 long ago taken from her African brood in her tender childhood by the Hon Van Riebeeck and educated in his house as well as brought to the knowledge of the Christian faith and being thus transformed from a female Hottentoo almost into a Netherland woman..."Â (Malherbe, 1990: 62).This sets the scene for a complete European takeover of the Cape, including the notion that the native is an inherent savage. This prejudice would later persuade generations of whites that African people were inherently inferior.

Krotoa 'Eva' van Meerhof transcended all impossibilities of her time. She was not afraid to love or to be judged by both the worlds she was living in. She lived her short life knowing that she could love and be loved. Happy Valentine's month, Krotoa.

Reference

Malherbe, V. C. 1990. Krotoa, called "˜Eva': A Woman Between. Cape Town: UCT Centre for African Studies.