|

|

|

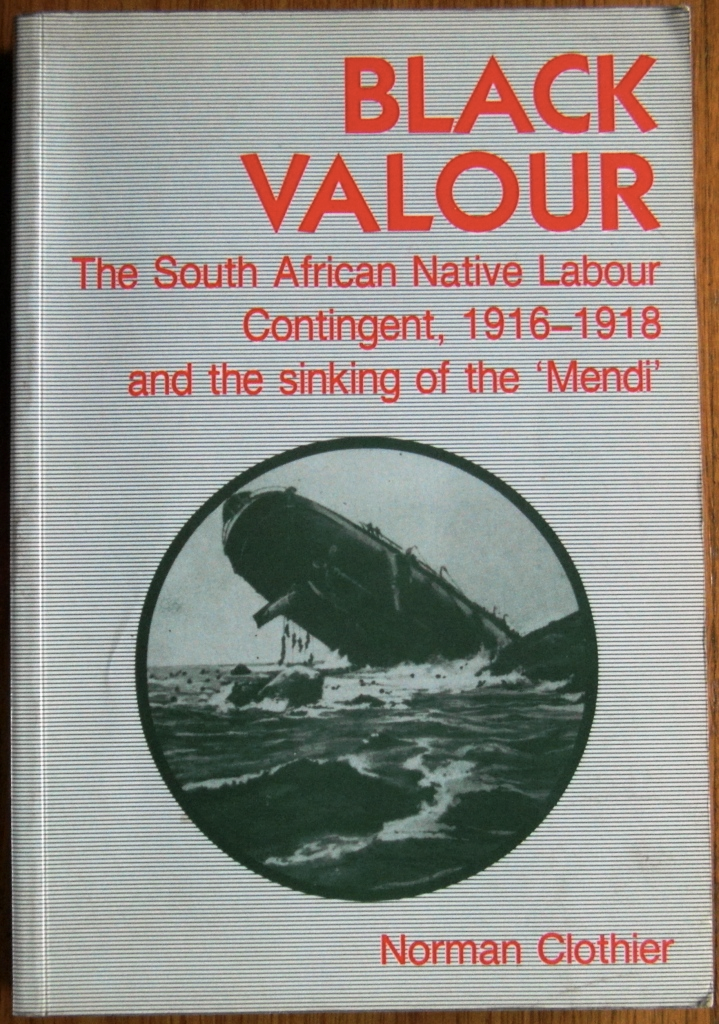

This project commemorates in 2017 the centenary of the sinking of the SS Mendi that occurred on 21 February 1917, paying tribute through the academy and the arts to the South African Native Labour Contingent and particularly to the soldiers on the Mendi who died en route to serve South Africa and the British war effort during the First World War.

The project references the struggle against the Natives Land Act of 1913 as a reason why these men left their homes in rural South Africa to contribute to the war effort, and seeks to explore the roles played by black intellectuals such as Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi, Solomon T. Plaatje, and John Dube in the recruitment of men to the South African Native Labour Contingent, and in dealing with the aftermath of the Mendi tragedy.

Being black men in a war of competing imperialisms, the men of the South African Native Labour Contingent were not allowed to bear arms, but they contributed greatly to the war: digging trenches, unloading cargo, working on shipping docks, and performing other vital kinds of labour. The role they played is part of the hidden history of the war.

The Mendi left Cape Town in January 1917 carrying 823 passengers, most of whom were members of the South African Native Labour Contingent. On the fateful morning of 21 February 1917, in heavy fog and before she reached France, the Mendi was rammed by a merchant ship, the Darro, which was travelling at a high speed. The Mendi sank swiftly, and no lifeboats were lowered by the Darro. The sinking of the SS Mendi was arguably South Africa’s greatest military disaster, as more than 600 men lost their lives in a time of war, in about 20 minutes.

On board the Mendi was the Rev. Isaac Williams Wauchope, a Minister in the Congregational Native Church of Fort Beaufort, who is reported to have calmed his countrymen and inspired them to perform “the death drill” on the deck of the sinking vessel with the following words:

Be quiet and calm, my countrymen. What is happening now is what you came to do...you are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers... Swazis, Pondos, Basotho… so let us die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war-cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies.

As the ship sank the men reportedly burst into a loud chant of Tiyo Soga’s song “Lizalise idinga lakho, Thixo Nkosi yenyaniso” (Fulfil thy wish, oh Lord, let all the nations receive thy salvation). This was the same song that was sung when the ANC had opened its inaugural conference in Waaihoek on 8 January 1912. According to certain narratives, the men of the SS Mendi went down singing and stamping their feet on the deck of the ship, hence their last dance was called the “death dance”.

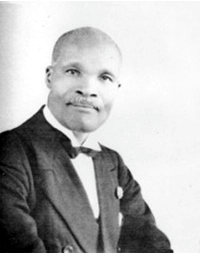

Though some historians have disputed exactly what happened on the deck of the sinking ship, what is fascinating about stories of the Mendi is the way they have contributed to the work of the imagination. A number of artworks and films, and a play “Ukutshona kukaMendi: Did We Dance?”, have emerged in the post-apartheid context. The Mendi story is also part of a long history of black poetry in South Africa. The great imbongi yesizwe S.E.K. Mqhayi wrote the recruitment poem for the South African Native Labour Contingent, “Umkosi wemi-Daka” (“The Black Army”), and after the Mendi tragedy, he also wrote the famous poem, “Ukutshona kukaMendi (“The Sinking of the Mendi”), which portrays redemption in tragedy.

[Left: S.E.K. Mqhayi, 1875-1945]

On hearing news of the Mendi tragedy, all members of the South African Parliament in 1917 stood for a minute of silence to commemorate those who had died. At the same time, however, black families in the rural areas were stuck in a tragic limbo, not knowing whether their family members on board the ship had drowned or survived. As evidenced by a letter written by Solomon T. Plaatjie on behalf of a member of his family to plead with the British authorities for a list of Mendi survivors, information was slow in being released and reaching the families concerned. Moreover, while medals for bravery during the war were given to the families of white and coloured soldiers who had lost their lives, no such medals were awarded to the families of the South African Native Labour Contingent.

In order to redress this history, the South African Department of Defence will in 2017 be honouring families of those black troops who lost their lives in the Mendi disaster. The Department will in 2017 be holding a ceremony to commemorate the South African Native Labour Contingent and the sinking of the Mendi at the lower campus of the University of Cape Town (UCT).

[Right: Mendi memorial created by South African artist Madi Phala for UCT’s lower campus in 2006.]

The choice of UCT as a site for the military commemoration is significant: the former Rosebank Showgrounds, now part of UCT’s lower campus, was used to billet the South African Native Labour Contingent en route to the Western Front, and was where the men of the Mendi spent their last night on South African soil.

The Mendi Centenary Project intends to create a complementary conversation with this military ceremony by hosting a series of events at the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town.