Please note: this material is copyrighted, but may be used for personal use without charge on condition that the author and source are acknowledged.

How to Write a Philosophy Essay

Contents:

1. Five Steps

2. Structuring your paper

3. Some useful hints

4. Logical Structuring

Writing a philosophy essay is not easy. It requires lots of thought, careful planning, meticulous writing and rewriting. Start working on your paper early so that your final product is not written in haste.

1. Five Steps

Following are five steps that might assist you in writing a philosophical essay. If you have an alternative tried and trusted method then feel free to employ it instead.

1 Think

Give sustained and serious thought to the topic that you have chosen or which has been assigned to you. Make sure that you understand all the issues that it involves. Reading good articles on the subject can facilitate one's thinking and take one's argument to a higher level of sophistication. If possible, try to formulate your solution to the problem (even if it is not original) or try to understand why you are undecided. (Is it because you are confused or is it because you appreciate the philosophical problem and can sympathise with different views about it? If the latter, then remember that you must be able to explain this indecision.)

2 Brainstorm

Jot down all the arguments and points that you think are relevant to your essay topic.

3 Plan

Carefully plot out the structure of your essay, paying close attention to its logical sequence and development. Although some students will be able to structure their essays well without laying out an extensive plan, it is advisable to plot out the logical sequence of one’s essay in quite some detail. It is only then that many students really can see whether their essays and the component arguments are sufficiently well organised.

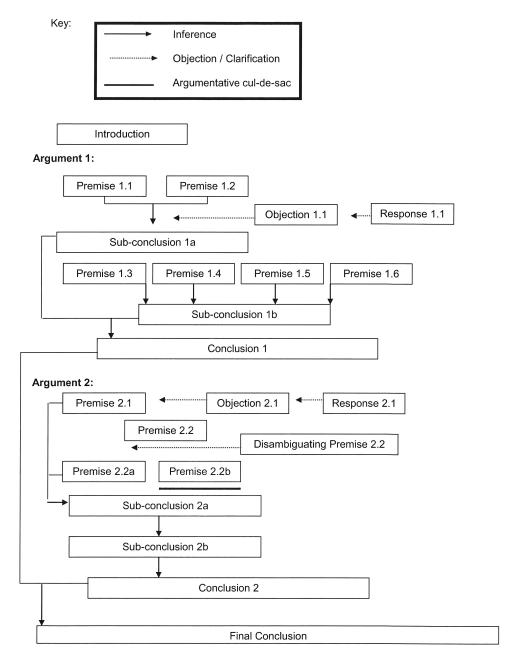

An outline of a very short sample essay can be found on page 11. Most essays will contain more than merely two arguments (as this one does). Moreover, there are very many structural permutations for the arguments that an essay might include, and thus the particular examples provided are not intended to be prescriptive, but rather are illustrative.

4 Write

Fill out the skeletal plan of your essay by writing your first draft. Carefully choose each word you use and accurately formulate each sentence. Write in clear, intelligible language. You will often find that you have to alter your original plan because, in writing your paper, you discover its flaws. That is perfectly acceptable, but then you should revise your plan in the light of your changes before proceeding further with your writing.

5 Revise

Revise the paper as many times as you like. Read it with a critical eye and make the requisite changes. It is usually preferable, at least before writing your final version, to wait a while. Often arguments that appear clear and compelling when we formulate and write them, can be seen to be either confused or otherwise mistaken a few days later when we are no longer immersed in them. After making the final revisions, read the paper once again to check for residual problems before submitting it.

2. Structuring your Paper

There are no hard and fast rules about how a philosophical paper should be structured, but the following might be a helpful guide:

-

Introduction

Try to avoid trite introductions (and conclusions). An introduction does not have to be gripping (although that can help). However, it should be informative. Stating the obvious does not fulfil that function. One good way to start an essay is by clarifying what the problem is. Sometimes the most difficult task is determining how best to cast the problem. Another important task for the introductory paragraphs is to clarify key terms or concepts that might otherwise be ambiguous. Thus the introduction is not something to be treated lightly. Give it a great deal of thought. The rest of your essay can rest on what you say in the introduction. It is also often helpful to tell the reader, in your introduction, what you plan to do in the essay.

-

Arguments

The arguments you advance are the core of your essay and it is crucial that they are rigorous and logical. Argument and analysis cannot be replaced by assertions or unsubstantiated opinions. Do not assume or merely assert crucial propositions. Sometimes it is acceptable to assume non-crucial ones, but then you should make these assumptions explicit. Make sure that your argument unfolds clearly and logically. Usually, each step of the argument (except the first) should follow from the step(s) before. Do not make any leaps of inference. Each step in your argument should be made explicit. It is often helpful (within reason) to "signpost" your essay - that is, to alert your reader to what you are going to do next or what you have just done. That can be good even where you have indicated your intentions in the introduction because it helps to make the reader aware of what point in the argument has been reached. Examples are usually a productive way of making one's arguments clearer. Always ask yourself how your opponent might object to what you are saying. Do not ignore obvious and important counter-examples and objections to your arguments. Even if you don't agree with these objections, you must raise them and argue against them. It is often helpful to get a friend or family member (but one who is willing to criticise your paper, not merely compliment you on it) to read your essay and tell you where it is not clear or where somebody might object.

-

Conclusion

An important part of an argument is its conclusion. It is essential that a conclusion follow from the arguments that have been advanced to support it. A conclusion does not have to be a sweeping generalisation. Modest conclusions can also be important, but be careful not to argue only for trivial and uninteresting conclusions.

3. Some helpful hints

-

Your essay title should be the assigned question or topic

Your essay title should be the specific question or topic you were assigned. Do not change it. The question or topic may not be as gripping as the creative title you have devised. However, we are not looking for creative titles in undergraduate essays. Instead we are looking for a display of various philosophical virtues. These include precision. Changing the question or title can introduce dangerous imprecision. If you pose or answer a different question from the one asked your essay could be off the topic.

-

Do not presuppose that your reader is familiar with the issues that you are discussing

Write as if your reader were an intelligent person who is unfamiliar with the material. As a result you need to:

-

explain all novel and technical terms and concepts as you introduce them

-

outline and explain arguments, examples, etc., rather than merely referring to them by name.

It is only if you do this that the reader can determine whether you really understand the arguments and examples to which you refer.

-

Avoid appeals to authority

In philosophy, it is the strength of the arguments that counts, not how many famous people (even famous philosophers) you have agreeing with you. A view is not right or even more plausible simply because some authority says that it is. Even equally competent philosophers can disagree about an issue. The way to decide between their views is to evaluate their arguments.

-

Recognise the limits of dictionary definitions

While dictionary definitions can be a helpful place to start philosophical deliberations, especially if one is stuck, such definitions should not be appealed to as decisive solutions to philosophical problems. Dictionaries reflect usage. Insofar as people use words in a philosophically unsophisticated manner, this will be reflected in a dictionary. Feel free to consult a dictionary but always look critically at what it has to say.

-

First person

In some disciplines, students are encouraged not to refer to themselves in the first person – that is by use of the word “I” (or “we” where a paper is co-authored). Instead they are told to refer to themselves as “the author” or to avoid referring to themselves entirely by employing formulations such as “this essay will argue”. Although this practice is alleged to be more objective, it is both strange and of dubious value. First, it makes for stilted writing. (In ordinary speech, referring to oneself in the third person is positively odd; and essays do not argue –authors of essays argue.) Second, referring to oneself in the third person, even if it does convey some impression of objectivity, does not make one’s thought or writing any more objective than it otherwise would be. The impression is thus illusory. Subjectivity is avoided not by referring to oneself in the third person but rather by the rigour of one’s argument. Referring to oneself in the first person is thus entirely acceptable – and indeed preferred – in a Philosophy essay.

-

Avoid crude relativism

Many students make the mistake of assuming that truth and morality are relative to people’s opinions – or, in other words, that everything is simply a matter of opinion. Whether or not you think that everything is relative, you would be advised not to assume that it is. Because the relativistic view is highly contentious, it is best not to rest one’s argument on such a claim. Moreover, if everything were merely a matter of opinion, and every opinion were really as good as any other opinion, there would be no point in arguing about anything. But it does seem to be appropriate to argue about some things. (To see this more vividly, imagine that your tutor fails your essay solely because he or she does not like you. Is it really merely a matter of opinion whether your tutor has done you an injustice or is it actually an injustice?)

-

Avoid religious (and other controversial) assumptions

Many (but not all) students with strong religious convictions assume the truth of certain religious beliefs in the process of arguing for some conclusion. Given that such beliefs are highly controversial, assuming their truth in a philosophical argument is deeply problematic. This is not to say that all religious views are false, but only that one ought not to assume, at least for the purposes of a Philosophy essay, that they are true. The remedy, however, is not to devote each essay to arguing for the existence of God and the Divine origin of the Bible. Unless those are the philosophical topics at hand, focusing on them would be a distraction from the topic of discussion. It is not the case that every philosophical question is a question in the philosophy of religion. In any event, much less depends on religious views than many people think. For instance, there can be theistic support for and atheistic opposition to abortion, and there can be religious defences of homosexuality and secular opposition to it.

None of the foregoing is to say that students must betray their religious convictions by saying things that they do not believe. There are many strategies that a religious person might employ, depending on that person’s beliefs and on the topic about which he or she is writing. In some circumstances, for instance, one might decide to discuss a particular argument or set of arguments for some conclusion rather than to establish whether the conclusion itself is true. Because there are both good and bad arguments for true conclusions, one can show why the bad arguments are bad even if one accepts their conclusion. (Obviously this option is not open if the question specifically requires that one assess the truth of the conclusion.) Alternatively one could try to develop an argument that does not make religious (or any other controversial) assumptions, but which nonetheless yields the conclusion one holds to be true. Yet another option would be to refine or reject whatever view one holds. Finally, one might decide to write on a topic that poses less of a problem.

-

Web sources should only be used with caution

If web sources are used, this should be done with caution. As anybody (with the technical capacity) can post something on the web, the safeguards of peer review that are employed by reputable academic journals are absent. This means that web sources may often be thoroughly unreliable. (This is not to say one should believe everything one reads in print, but articles published in good academic journals and books have passed through a process of close review that makes them less unreliable.) Thus one should use particular discretion in the kinds of web sources one consults.

-

Avoid plagiarism

The use of another author’s words or ideas without acknowledgement, is a form of dishonesty, and is a serious academic offence. Summarising somebody’s ideas with acknowledgement is acceptable. However, merely substituting individual, words, phrases or sentences, while preserving the character or structure of the original work, does amount to plagiarism. For more details about what does and what does not constitute plagiarism, please see the next section – “Avoiding Plagiarism”.

-

Avoid excessive quoting

Avoid excessive quoting, even if you do reference the source. It is not possible to assess your understanding of the issues if large parts of your essay consist of quoting the words of others. In general, one should quote only when some important purpose is served by doing so.

-

References should be complete and clear

There are various citation or referencing conventions. Although any one may be used, it is preferable to use those that are more reader-friendly. (To determine which these are, ask yourself whether a given convention makes it as easy as possible to read the text without being distracted by the references but also as easy as possible to refer to the full citation if needed.) Whichever convention one uses, however, one must provide the following information:

-

Journal articles:

Author, title of article, journal name, volume and number, year, and page number(s). -

Books:

Author, title of book, place of publication, publisher, year and page number(s). -

Articles in books:

Author, title of article, editor and title of book, place of publication, publisher, year and page number(s).

4. Structuring an Essay Logically

Your structure should list the actual premises, objections and conclusions rather than their numbers.