THE GREEN & SEA POINT SYNAGOGUE OPENS

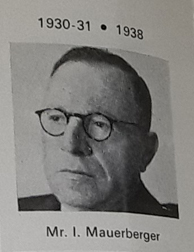

On 26th July 1934 the committee met for the first time in the almost complete Synagogue. Present were AM Jackson, S Kaplan, H Arenson, H Marks, I Mauerberger, JL Pearce, A Sacks and N Wittenberg. Apologies were received from Rael Gordon and Henry Hermann. They were aware that they were making history - despite the Quota Act, despite the depression, despite the Greyshirts, they were putting down their roots as proud Jews. Theirs was the first purpose-built synagogue on the Atlantic seaboard. It was described as being octagonal in shape and extremely modern in design being characterised by its simplicity and lack of ornamentation and could accommodate over nine hundred people.[i]

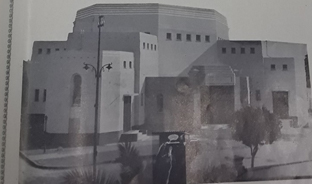

The synagogue, recalled Dr E Kirsch[ii](who celebrated his barmitzvah there the next year), was a much smaller star shaped building than originally planned, built in a marshy area in the grounds of Bordeaux, the Graaf residence. (The Jewish Chronicle report of the consecration 7.11.1934 described it as having a very beautiful octagonal shape, well-lit and ventilated.) The Aron Kodesh was panelled in teak, the lighting was in the form of fluorescent tubes in the form of a Magen David on the central ceiling and wings and the seats were of hard wood, which a generous donor later upholstered in red leatherette. A marble plaque in the foyer honours the executive and Committee of that day. There were Talmud Torah classroom in two of the wings which were used as part of the Shul for Festivals. In this way the Shul could accommodate about 800 worshippers.[iii]

The recently erected Green and Sea Point Synagogue. SA Jewish Chronicle, Rosh Hashanah 1934

This was ambitious considering that two years earlier the wisdom of building a synagogue had been widely questioned, the immigration of their families from Eastern European was no longer possible and only 127 families had expressed interest in joining a congregation.

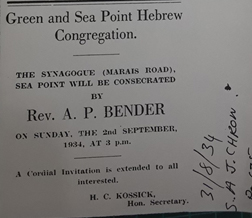

And, on 2nd September, in the presence of Mayor Gradner, Jackson officially opened the building which was consecrated by the Rev. AP Bender with a service by their rabbi, Rev P Rosenberg. Rev Bender said he was reminded of the time thirty-two years previously when he had walked on the second day of Rosh Hashanah from Cape Town to Sea Point to hold a service in the Sea Point Town Hall and now those living in Sea Point had a permanent House of Worship. Rabbi M Ch Mirvish congratulated all concerned in the building up of the synagogue for which they had waited so long saying that it was these smaller synagogues in the country which helped to keep together Jewish unity.[iv]

It did not take many years before no one could refer to the Sea Point synagogue as one of the smaller synagogues in the country!

To quote Rabbi Shrock[v]: “Thus the idea which had germinated in the minds of those estimable young men eight years earlier, had at last reached fruition. For the Jewish community of Sea Point generally and for its handful of resolute leaders in particular, it must indeed have been a proud day.”

The committee offered the presidency to Mr Gutman but he declined due to ill health and passed away on 10th February 1935. His daughter Bubbles recalled that as the synagogue was completed before Rosh Hashanah, he was at least able to spend one Rosh Hashanah in his own shul whose beginning had taken root in his own home.[vi] Those very special first High Holy Day services were conducted by Rev Rosenberg and Rev Pakter, who also acted as the Shammas, Torah reader and Schochet and served the congregation with great devotion and loyalty for many years.

As for Rev Pakter, Mark Kaplan complained that he had almost completely changed the 16-year-old boy’s life.

“As I was the only available Cohen on Saturday mornings, Rev Pakter religiously called my parents’ home every Saturday literally grabbed me by the ear and dragged me to the Shul so that the congregation could have a service. I was a pupil at the South African College and every Saturday morning during the winter months we played our rugby games against other schools and cricket games in the summer. Having to be present every Saturday morning in the Shul completely ruined any chance I had of becoming a famous sportsman.”

In November 1934, in their new shul, committee member Israel Mauerberger had the pleasure of watching Rev Bender and Rev Rosenberg marry his son Teddy to Levia Goodman.[vii]

The bride looked charming in a gown of heavy ivory satin with a triple cowl neck, long full sleeves and a long train, carrying a sheaf of St Joseph lilies. Estelle and Jeanette Mauerberger were attractive flower girls in Kate Greenaway frocks of pale green organdie, poke bonnets, pink mittens and shoes, Blanche Goodman was the maid of honour in green lace trimmed with green taffetas with the bridesmaids Sally Mauerberger and Fanny Kaplan in similar dresses in pink lace and taffeta. Pole holders were David Schrire, Sam Goodman, Harold Goodman, Jack Ipp with Dr Isidore Schrire as best man. Archie Sacks, G&SPHC president presented the young couple with a golden cup as theirs was the first wedding to be solemnised in the Sea Point Synagogue and they left that afternoon on honeymoon to England on the Winchester Castle.[viii]

REFORM MOVEMENT ARRIVES IN SOUTH AFRICA

The 1930s also saw the unquestioned monopoly of Orthodoxy challenged with the late arrival in South Africa of the Progressive Reform movement (known in Britain as Liberal Judaism). It had begun in 19th century Germany, taken root in America but had not been established in South Africa before Rabbi M Weiler arrived in Johannesburg in August 1933. His arrival had been precipitated by a letter from a young English immigrant to Cape Town in April 1929 to Hon Lily Montagu, the honorary secretary of the World Union for Progressive Judaism in London, asking her to help a group of young people in the city to embrace Liberal Judaism. She asked Professor Avram Zvi Idelsohn who was due to visit South Africa to find this group of young people, and help them launch a Liberal movement. Little happened, so she arranged to send Rabbi Weiler to do just that. Rabbi Weiler believed that Judaism had survived through the centuries because it could adapt to changing conditions with the Reform movement representing an adaptation to modernity and he wanted to bring disaffiliated Jews back into the fold.

His arrival had reverberations in Sea Point because in his 1934 G&SPHC AGM address in the Sea Point Town Hall, Chairman AM Jackson remarked on their gratification in accomplishing the building of a synagogue, but also stated that while he was opposed to any alteration of the synagogue service, he thought the time had arrived for orthodox leaders to get together and eliminate some of the restrictions.[ix]

The orthodox rabbinate threatened by the establishment of a Reform Movement had been making noises about instituting changes. Already in October 1931 B Guinsberg told a meeting of Johannesburg’s United Hebrew Congregations (UHC) that Chief Rabbi Landau was considering inaugurating a series of services in the Yeoville Synagogue that would embrace certain “mild reforms”. Guinsberg and Rabbi AT Shrock, the Yeoville rabbi, turned up at a meeting to launch the new reform movement and told the meeting that if they abandoned the idea of doing so and of hiring a reform rabbi, they promised to institute certain modification of the service and the inclusion of the English language. At the UHC AGM in May 1932, Landau complained that his “mild reforms’ such as popular sermons, some English prayers and some Friday lectures had not managed to attract the younger generation.[x] Such statements from a Chief Rabbi or the chairman of an orthodox synagogue indicating a certain degree of flexibility would not have been permissible or possible fifty years later when the chief rabbinate had become more conservative and authoritarian.

Indeed the G&SPHC’s own Rev Rosenberg had written on 30 November to Lily Montagu claiming that he was the founder of the G&SPHC synagogue which he had originally intended to be liberal in spirit, but as he had found it was being run as an extremely Orthodox Synagogue, he felt impelled to resign his position as he did not feel in sympathy with the customs and principles of Orthodoxy. All rather confusing, as he was not a founder, he knew what sort of synagogue was employing him - there were no others - he would have no authority to change its policies nor did he resign. He also asked for financial support saying that the Orthodox would be antagonistic towards him if they knew he favoured liberal Judaism.

Rosenberg did, however, provide some interesting statistics. He claimed that Cape Town had 10,000 Jews, only 3,500 of which were fee-paying members of Orthodox congregations with a further thousand hiring a hall for the High Festivals, the rest belonged neither to a synagogue nor to a church. He felt confident that such a synagogue would draw a great many of them. Lily Montagu thanked him for the letter, offered no financial support and told him to contact Rabbi Weiler.[xi]

When a Reform Congregation was started in Cape Town in 1944, they elected as president Dr Herman Kramer. He was a surprising choice as Reform president, Irwin Manoim wrote,[xii] as he had been a founder and long-time G&SPHC president but he evidently had experience with the business of founding religious institutions and was a popular and well-networked doctor.

President of the Green and Sea Point Hebrew Congregation and then of the Reform Congregation and vice president of SAUPJ

As for Rev Rosenberg, he resigned the following year but his principles that impelled him to resign from an orthodox congregation were short lived as he was subsequently employed by orthodox synagogues in Jeppe, Bertrams, Windhoek, Witbank and Middelburg (for about 20 years until his death in 1993) with, however, a short spell at the Port Elizabeth Temple Israel in 1958[xiii] before once again returning to the orthodox fold, being described by JewishGen as an itinerant rabbi.[xiv]

With both the G&SPHC president and its minister/cantor attracted to the rival Reform Congregation, identification with the movement must have been popular despite strong attacks from the Orthodox, particularly from the Garden Shul’s Rabbi Abrahams who arranged a series of meetings on the perils of Reform and when he became Chief Rabbi in 1951 tried to ban his rabbis, cantors and Hebrew teachers from meeting with them. There were threats of boycotts and economic sanctions against those who joined Reform and the community was told that its main purpose was to lead the children to the baptismal font.[xv] The G&SPHC would face repercussions later when it shared events with the Reform congregation.

Rabbi Abrahams tried to prevent the Reform movement from hiring communal halls – ostensibly on the grounds that Reform used an organ – no mention was made that the G&SPHC itself had an organ, and the only time its organ was to be found in its minutes was a 1948 complaint not about its use, but about its condition. Another time Rabbi Abrahams instigated an anonymous rabbi, thought to be G&SPHC’s Rabbi Shrock to make a pretend booking of the Zionist Hall to prevent Reform from using it over the High Holydays.[xvi]

The G&SPHC weathered the threats of Reform Judaism for the time being but the threats of antisemitism were on-going. Referring in that AGM speech to Smut’s words of the barking dog, Jackson went on to complain that Smuts’ warning issued in November 1933 had not been heeded. Smuts had issued an earnest appeal to the people of South Africa to discourage the spread of the “sinister and dangerous antisemitism” originating abroad and being spread in South Africa, and that “unhappy racialism” was “a poisonous weed and not desired here” and he had warned those taking part in engendering racial hatreds that they would be to blame in the event of any trouble.[xvii]

HITLER GAINS POWER – IMMIGRATION RESTRICTIONS

Once Adolf Hitler became Fuhrer of Germany, laws were passed removing Jews in Germany from government service, the legal profession, from editorial posts, limiting the number at schools and universities, and revoking their citizenship. Unable to earn a living, Jews were queuing at embassies trying to leave Germany.

The SA Nazi movement had become emboldened by the rise of Hitler. In May, Jackson (who was to become chairman of the Jewish Board of Deputies in 1946-1949) had formed part of a Board deputation to General Smuts to express their concern at the growth of antisemitism, including in the media. They told him they were advising people not to interfere with or attend meetings held by organisations like the Greyshirts, but this had only made their speeches more insulting and it was becoming increasingly difficult to restrain younger Jews from actively opposing them. The youth felt that they could not remain passive in the face of such provocation. Smuts asked the Board to continue advising restraint because if there were physical clashes their jails would be full of young Jews.[xviii]

Jackson used the occasion of the AGM to appeal to the audience to keep their temper in spite of the provocation and to restrain the younger men from doing anything that would lead to public violence. Non-Jewish opinion, he told them, was beginning to realise that Jew-baiting was only one form of denial of liberty and he believed that ‘the eternal persecution was largely instrumental in populating Palestine.”

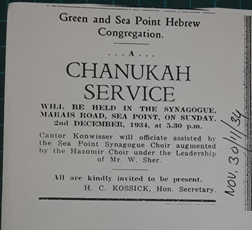

This is the first reference to Zionism but it was to be repeated in many sermons and messages. Prof Jocelyn Hellig has suggested that South African Jews of Lithuanian descent were inclined to express their identity through Zionism rather than through conventional religious forms. Cheder rooms always paid great attention to those festivals having a national theme. Posters preaching the Zionist message on all appropriate occasions were the standard decorations of Jewish communal halls throughout South Africa.[xix] In November Rev Rosenberg spoke about Chanukah at a meeting also addressed by Bertie Stern[xx] on the Habonim youth movement, hoping there would be sufficient interest to start a Sea Point gedud.[xxi] Their first Chanukah service in their own synagogue was advertised in the SA Jewish Chronicle of 30 November 1934 with Cantor Konvisser assisted by the Sea Point Choir augmented by the Hazomir choir. According to Ian Sacks, when the choir was first formed some girls were incorporated - were they the Hazomir Choir?

Jackson’s appeal for restraint was ignored, individual Jews throughout the country, especially those from the youth movements and socialists, were opposing the Greyshirt movement and public opinion sided with the Jews - it seemed only fair that they opposed the Jew-baiting invective that was being hurled at them, as Nathan Berger described:

“A group of able-bodied young Jews took upon themselves the task of disturbing and breaking up gatherings by the Greyshirts glorifying the National Socialist philosophy in South Africa. Serious clashes took place between the Jewish avengers and the Hitler propagandists. Violence followed, bloodshed and arrests were a regular feature. Greyshirt mobs eventually retreated from the usual Town hall steps venue to new grounds in the suburbs too far and too dangerous for their opponents to reach.”[xxii]

Jackson’s fears came true when on 2nd April 1936 the Greyshirts planned a “Monster” meeting on the parade after the Cape Town City Council had refused permission for the use of their hall. There was a clash, people were injured and some of the young Jews were arrested - but later acquitted.[xxiii]

Not surprisingly considering his leaning towards Reform and his disagreements with the committee, in 1935 Rev Rosenberg resigned his position to be replaced in 1936 by Rabbi Dr IH Levine (who left in 1940 after getting his doctorate) and Cantor Katzin – people came from all over the peninsula to hear him conduct his first service. He developed an excellent choir which attracted larger attendances at the services and was their cantor for thirty years. Rabbi Dr Levine showed evidence of profound scholarship in his sermons as well as an ability to transmit a noble evaluation of Jewish heritage. The community began to increase and, as conditions for South African and world Jewry began to deteriorate, they began to show an increasing interest in Jewish affairs and Jewish identity.

With the Nazi party in power, life in Germany for Jews became more and more difficult but governments, although sympathetic to their circumstances, were shutting their doors. The Cape Times had increasingly been calling for curbs on undesirable immigration of ‘unassimilable people (code name for Jews) from countries where democratic ideals were unknown and western concepts of morality are quite unappreciated”. Die Transvaler, the National Party mouthpiece, was openly antisemitic and advocated a quota system for Jews in the professions, trades and industries. In 1937 Eric Louw tried unsuccessfully to introduce an Alien’s Amendment Act to deprive Jews of the rights to practice certain trades and professions and the Transvaal National Party Congress decided that Jews were not eligible for party membership.

As the original Quota Act had not included Germany, an Alien’s Act was passed in 1937 to remedy the fault. Jews were not mentioned by name, the Government hinted that they were targeting communists, but no one was fooled. Everyone knew who the aliens were that the act would exclude. In a Parliamentary debate DF Malan of the Purified National Party blamed the Jews for the necessity of the law as they had ignored his previous warning to control immigration.

“They have not done so. The Jews in South Africa are to blame for the state of affairs with which we are trying to deal.”[xxiv]

The Stuttgart was hastily charted to bring Jewish refugees to South Africa before the act came into force. Alma and Ludwig Wolff were passengers and when they learnt that only married refugees were allowed entry, the German consul at Las Palmas married them and they were remarried at the G&SPHC as soon as they arrived. Alma’s parents died in the Sobibor gas chambers.[xxv]

[i] The Sea Point Synagogue in Marais Road, IN SA Jewish Chronicle, 20.4.1934

[ii] Kirsch Dr E, “Our congregation”, G&SPHC Rosh Hashana Annual, 1993 – 5753, 73

[iii] Kaplan, Mark, op cit 1974 – 5735, 10

[iv] The SA Jewish Chronicle, 7.9.1934

[v] Shrock, Rabbi AT, Op cit, 21

[vi] Harris, Bubbles, “Tribute to the late Leah & Joseph Gutman”, G&SPHC Rosh Hashana Annual 1996 – 5757, 42

[vii] Levia Mauerberger was to sit in the same shul seat M7, for over seventy years and their grandson, Kevin Derman, served the shul as choirmaster for twelve years. In 1975 Teddy, was elected Mayor of Cape Town.

[viii] Newspaper cutting, 23.11.1934

[ix] Annual General Meeting, G&SPHC, IN SA Jewish Chronicle, 26.10.1934, 779

[x] Manoim, Irwin, Mavericks Inside the Tent. The Progressive Jewish movement in South Africa and its impact on the wider community. UCT Press 2019, 27-39

[xi] Manoim, op cit, p101- 102, also e-mail from Manoim, 10.5.2020

[xii] Manoim, op.cit, 110

[xiii] Manoim, op cit. 110

[xiv] Rabbis & Cantors - JewishGen KehilaLinks. kehilalinks.jewishgen.org › capetown › Rabbis_&_Cant...

[xv] Sherman, Rabbi David, Pioneering for Reform Judaism in South Africa, Temple Israel, Cape Town, no date, 12-13

[xvi] Manoim, op.cit, 129-130

[xvii] “General Smuts Protests Spread of Anti-semitism by South African Nazis” IN JTA, November 3, 1933

[xviii] Schrire, Gwynne, South African Jewish Board of Deputies (Cape Council): A Century of Communal Challenges, SA Jewish Board of Deputies, 2004, 49

[xix] Simon, John, “At the Frontier – The South African Jewish Experience”, IN Gilman, Sander & Shain, Milton, Jewries at the Frontier: Accommodation, Identity, Conflict, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago 1999, 73

[xx] Attorney Bertie Stern, known as “Sandpiper “was a keen scout master who helped found Habonim in Cape Town and ran the Habonim Camp in the 1940s and 1950s. Later, as chairman of the South Peninsula Dramatic Society, he purchased a dilapidated bowling alley in Muizenberg and turned it into the Masque Theatre.

[xxi] SA Jewish Chronicle, 30.11.1934, 883

[xxii] Berger, Nathan, In those days, in these times, spotlighting events in Jewry - South African and General, Johannesburg, 1979, 64

[xxiii] Schrire, Gwynne, “Jewish Self-Assertion and the Grey Shirts Movement”, Jewish Affairs, 2003, 59:1

[xxiv] Shain, Milton, A Perfect Storm: Antisemitism in South Africa 1930-1948, Jonathan Ball, Cape Town 2015, 148

[xxv] Rogow, Rosalie, as told to Schneider, Moira, SA Jewish Report, 10.11.2016