What does that mean for their congregation? Probably very little. The problem is that the right-wing swing of the rabbinate in Johannesburg is not replicated in the attitudes of the Sea Point congregation. The saying goes that you can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink. You can provide the congregation with a Lubavitche rabbi but that does not make it Lubavitch and they have remained what Dr Hellig has called Non-observant Orthodox Jews who attend the synagogue on Friday evenings enjoying the singing - although, without a microphone, some cannot hear the sermon - as an opportunity for social engagement and a form of identification.

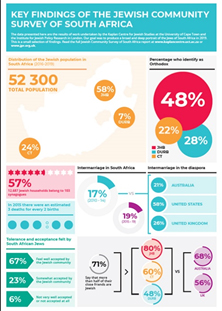

The surveys done by the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape Town indicate that the Johannesburg rabbinate in their push to get rid of Rabbi Steinhorn and replace him with someone more attuned to their more conservative way of thinking was short sighted. The surveys clearly show not only that the Cape Town Jewish community differs from the Johannesburg Jewish community in terms of religious ‘orthodoxy’, but also that there has been a shift towards secularism and Progressive Reform, with a drop in those regarding themselves as traditional towards a more orthodox lifestyle.[i] Yet those regarding themselves as “Orthodox”, still only represented a fifth of the community with only 2% regarding themselves as strictly Orthodox/Haredi/Chasidic.

Of the 19% identifying themselves as Orthodox in the 2019 Kaplan Centre survey of the affiliated Cape Town Jewish community[ii], only 7% keep Shabbat, only 9% do not drive on Shabbat, 8.5% do not use electricity and only 7% refrain from both. To a real Orthodox Jew, those Orthodox Jews were not orthodox. There was no statistical difference from the pre-Rabbi Wineberg 2005 Kaplan Survey which found only 8% of the Cape Town community did not drive on Shabbat (Bruk, 2006) and the 2019 Kaplan Survey (since the arrival of Rabbi Wineberg) which showed that only 9% did not drive on Shabbat. No matter what the rabbis wanted, South African Orthodoxy was still more a form of identification than of religious observance, and it was promoted more by family tradition than by any ideological conviction.

In the 2019 survey nearly 65% describe themselves as either Traditional or Secularly/Culturally Jewish.[iii] Between 2005 and 2019 the surveys showed an increase in those identifying themselves as secular/Just Jewish from 18% - 22%, in those who did not know from 0 to 6%, and the Traditional numbers were now split between traditional and orthodox with the behaviour of most of the orthodox being the same as the behaviour of the traditional when Shabbat observance was taken into consideration. By contrast, in its “2020 Israel Religion and State Index”[iv] Hiddush reported that 65% of Israeli Jews self-identify as secular, 10% as ultra-Orthodox, 11% as Zionist Orthodox, and the remaining 14% as traditional-religious.

The behaviour of Cape Town Jewry gives a clear example of why a Lubavitch rabbi is a mismatch. When the new Chief Rabbi, Dr Warren Goldstein took over in 2005, he appeared to encourage the institutionalisation of certain Ultra-Orthodox customs in the community, by absenting himself from public gatherings where women were allowed to sing or Reform rabbis to speak.[v] This behaviour broadened the gap between secular and religious Jews in Cape Town as could be clearly seen in the Kol Isha issue that roiled the Cape Town community in 2016[vi] when the Cape SA Jewish Board of Deputies was taken to court because women were not allowed to sing at the communal Holocaust commemoration services. Chief Rabbi Goldstein even flew down to Cape Town to assert his views. In the end it was agreed that the ceremony would start with a woman singing, followed by a break to enable those with halachic problems about hearing a women’s voice to enter. The synagogues refused to display posters with the starting time, so new posters had to be designed. The result? Over a thousand arrived for the beginning when the woman would sing; only a handful arrived for the second male-only part.

A further example was the Yom Kippur services held in 2020 during the Covid-19 lockdown. The Reform-Progressive Congregation screened their services at the usual time on zoom – large numbers tuned in for it, far greater than merely the Progressive membership. These additional on-line worshippers came from those in the 92% of the community who had no problem with using electricity and computers to listen on Yom Kippur to services which included singing women.

Many of the issues in a thought-provoking article, “Can Modern Orthodoxy Survive”, by Prof Jack Wertheimer, are also relevant to the mindset of the upcoming generations of young Jews today, who will be the leaders of the Marais Road Shul in decades to come. At school they will have been taught about the South African constitution which prohibits unfair discrimination on grounds which include race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth. and they will have been socialised to view the world through non-discriminatory lenses. They will increasingly view certain Jewish orthodox practises as being discriminatory.

Although Wertheimer is a professor of American Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary, his concerns are equally applicable to us here in South Africa looking towards the shul’s centenary and beyond.

Undoubtedly, the most hotly debated set of issues concerns the status of Orthodox women. Sexual equality is now taken for granted in most Modern Orthodox homes, and holding males and females to different standards is increasingly unthinkable. Other debates centre on the proper treatment of homosexuality in the Orthodox community; how the community should relate to non-Orthodox Jews… and more. The urgent question for Modern Orthodoxy is which values can be accommodated without undermining religious commitment and distorting traditional Judaism beyond recognition—and, conversely, what losses will be sustained if Modern Orthodoxy should undertake more actively to resist the modern world in which its adherents spend most of their waking hours. ...That is one reason why today’s unfolding culture wars within Modern Orthodoxy carry far-reaching implications.”[vii]

These are not insignificant issues. The South African constitution grants everyone the right to freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief and opinion. These are questions that come up around Shabbat tables and have to be factored in. In addition to providing activities to make the shul a welcoming, relevant and accessible place to members of all ages, the synagogue also has to consider how to make its values acceptable to youth who have been brought up in the new South Africa, with all its challenges. Synagogues hold the potential for perpetuating Jewish life by nurturing Jews where they live, by creating and instilling a sense of rootedness in the traditions of our people and a sense of belonging to that people. Are they to be laagers or open tents? A place that will only assist in carrying out the rites of passage, and be visited on the High Holy Days, or a place that will ensure that our faith that has carried us through the challenges of two thousand years will continue on a regular basis to support and strengthen us with the beauty of its values into the challenges of the uncertain future? This is our legacy and we must pass it on to those who will follow.

When the foundation stone was laid in 1934, Adv Morris Alexander said the synagogue stood like a monument to the traditions they had inherited and he hoped the congregation would be founded on the pillars of unity, brotherly love and peace. The secret of Jewish survival is adaptability and the ability to go to the sources and what has been called the closing of the religious mind does not augur well for the future generation brought up on openness and acceptance of diversity. The synagogue has successfully adapted to the changing political and religious realities in South Africa. It must also consider adapting to the current changing realities in order to make the services as relevant to the future worshippers, to the 90% who do not keep Shabbat. The late British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks said:” If we truly wish to hand on our legacy to our children, we must teach them to love it.” [viii]

[i] The 2019 survey shows significant differences between the Jewish communities of Johannesburg and Cape Town, with 48% in Johannesburg self-identifying as either Orthodox or strictly Orthodox, compared with 22% in Cape Town, 18% in Johannesburg self-describe as Progressive or Secular, compared with 40% in Cape Town. These differences manifest in a variety of other indicators.

[ii] Kaplan Centre, 2019: Survey of the affiliated Cape Town Jewish Community, November 2019

A snapshot of Cape Town's Jewish Community, 12-13

|

CAPE TOWN RESULTS |

1998 |

2005 |

2019 |

|

Don’t know |

1% |

0 |

See below |

|

Secular/ Just Jewish |

16% |

18% |

22% |

|

Reform/ Progressive |

10% |

13% |

18% |

|

Traditional |

67% |

64% |

32 |

|

(2019 only) Orthodox |

|

|

20% |

|

Strictly Orthodox |

6% |

5% |

|

|

2019 Strictly Orthodox/Haredi/Chasidic |

|

|

2% |

*In 2019 don’t know category was divided into Mixed religion 3%, Not Jews 1% and Other 2%

[iii] 27% self-identify as Secular/Culturally Jewish, 11% as Progressive, 38% as Traditional and 19% as Orthodox

[iv] http://hiddush.org/article-23439-0-2020_Israel_Religion__State_Index.aspx 2020 Israel Religion & State Index - Hiddush

[v] SA Jewish Report, June 3-10 and November 18-25, 2005, In Herman, Chaya , “The Jewish community in the post-apartheid era: same narrative, different meaning” IN Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, no 63, 2007, pp. 23-44

[vi] Board sued in Equality Court over 'Kol Isha' - SA Jewish Report

www.sajr.co.za › organisations › 2016/04/06 › cape-board-sued-in-eq...

[vii] Wertheimer, Jack, ‘Can Modern Orthodoxy Survive?’, Mosaic, 3.8.2014

https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/2014/08/can-modern-orthodoxy-survive/

[viii] Sacks, Rabbi Jonathan, Covenant and Conversation, Parshat Matot Masei