In 1977 president Shabse Sive reported that “During the past year developments in South Africa have caused concern for the future of the Jewish community. A small percentage of our members were emigrating to countries other than Israel.” He added on a more positive level that their total membership had been maintained and he extended a very warm welcome to their new members.

This was the first time a president in his Rosh Hashanah message had referred, even obliquely, to a concern for their future, because of the oppression in South Africa. On 16th June 1976 youth in Soweto marched from the Morris Isaacson School - a school funded by a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant - to protest against the introduction of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. Students from other schools joined in to be met with extreme police brutality. The original government figure claimed only 23 students were killed but the numbers killed ranged from 176 to 700, with over a thousand wounded.

Rioting spread like wildfire. In Cape Town the spark was the police decision that students could no longer study at their schools at night. On August 11th, school children from Langa, Nyanga and Gugulethu marched through the streets of the townships. The police broke up the march with tear gas, dogs and arrests and this led to rioting mobs and the burning of administration buildings and bottle stores. University of Cape Town students decided to march in support - 73 were arrested. In September there was a peaceful march of Black scholars through Cape Town followed by a march of 1,000 Coloured scholars - the tear gas loosed by the police over the city forced the shops and offices to close and stopped the traffic. The next day the city was sealed off to traffic and police used bird shot and tear gas to disperse the crowd of demonstrators and thousands of curious onlookers. Many passers-by collapsed when the police fired tear gas into the underground Strand Street concourse. Two visiting All Black Rugby players were caught in the tear gas while they were signing autographs. (The Springboks won.)

“Only a very small militant group (of students) is still in the townships.” reported Maria Tholo a Langa diarist,” Many of the older ones have gone across the borders to the camps. They have gone to learn to fight. They are all going to come back here as terrorists.”

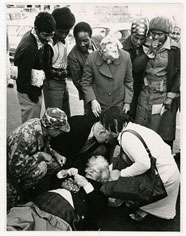

Left: Women overcome by teargas in Cape Town city centre, 1.9.1976 Photo Jim McClagan;

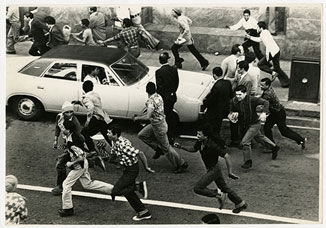

Right: Crowds scatter up Darling Street as police fire teargas on Grand Parade, 9.9.1976

The choking of Adderley Street brought home the truth about the riots to white South Africa. This was no longer something taking place in a remote black township or on the pages of a newspaper. Most White bystanders were seeing the police in action for the first time. Herzlia along with many other schools was being guarded by volunteers and scared parents were keeping their children at home. A three-day strike was called and approximately 100,000 workers went out on strike. Prime Minister Vorster’s Government would not budge and responded with repression and token reforms.

“South Africa will not be blackmailed into giving One Man One Vote,” he threatened. Minister Jimmy Kruger warned of what he viewed an even worse fate - “There is no other option but separate development”, he said.” We will have to learn to love it, warts and all, because... the only other possibility is One Man, One Vote and a Multiracial Parliament.”

It was calculated that between June 1976 and October 1977, there were 700 publicly recorded deaths in South Africa including that of the Witwatersrand Jewish welfare officer, Dr Melville Edelstein, who in a 1972 book What do young Africans think? had warned against the possibility of such violence. After a letter from the Black Sash, Rabbi Rosen told the committee that at the Yizkor memorial service he wished to mention the martyrs who had died in detention as well as those servicemen who had died defending the border. The committee discussed the matter at length before instructing Rabbi Rosen not to mention those deaths (29.7.1977). However, the committee was not to have much success in silencing the rabbi’s social conscience in other areas.

There was economic instability, the rand was devalued, and the UN Security Council passed a resolution condemning apartheid. White people were finally aware of the depths of black discontent and they were scared. Most Jews had always had a sense of moral ambivalence at living in an unjust society. Now they had a sense of fear. Conversations were about friends caught in the tear gas, of police brutality witnessed, of broken windscreens and disrupted business, about the security of the schools and whether exams would be disrupted. Before setting out on journeys, police were phoned for reports about the safety of the roads. Embassies were besieged by would be immigrants. A 1974 survey of 964 heads of Jewish households had shown that of children not living at home 18% lived abroad, of whom 38% lived in Israel, 28% in England 14% in America, 6% in Canada, and 2% in Australia.

President Shabse Sive was voicing what was on everyone’s minds. For Cape Town Jews the next year would become a time of grieving as every week more relatives, friends and acquaintances left and cars carried bumper stickers saying WILL THE LAST PERSON LEAVING PLEASE SWITCH OUT THE LIGHTS.