People were beginning to speak out about the evils of the apartheid society. In his Rosh Hashanah message Rabbi Fogel referred to the racist society existing in South Africa and their responsibilities as Jews both to assist the underprivileged and to support the needy in their own community.

As South Africans we are beset with many problems: in protecting our freedom and our economy from being undermined, in finding a peaceful solution to our racial difficulties, in raising the living standards of the underprivileged and many other responsibilities. We ought to be concerned with these issues and lend our support for a solution in a spirit of righteousness and justice to all. But as Jews we constitute a religious entity. As a Jewish community we also have many problems. We have to maintain our institutions for the well-being of the community and its continuity, synagogues, Hebrew schools and yeshivot, homes for the aged, homes for the handicapped and numerous social and cultural services.

Rabbi Rosen: After five years Rabbi Rosen had to leave because the government refused to renew his work permit. He had preached many sermons about the incompatibility of Judaism and apartheid, trying to influence the community to take a collective stance, calling on them to redress the wrongs in the society.[i] He had become active in interfaith work and meetings with people of other colours were viewed with suspicion. Although he was one of the pioneers of interfaith in Cape Town and was the founder/chairman of the Cape Inter-Faith Forum, the Council of Jews, Christians and Muslims, which became the Cape Town Interfaith Initiative, he had only got involved in interfaith dialogue because he saw it as a way to cross the bridge of racial schism in apartheid South Africa.

I started it,” he said,” Not because I was passionate about interfaith initiatives, but because it was one of the few ways to bring together communities across the colour divide. I came to it through a commitment to social justice. I was stunned to discover how ignorant other religious leaders were about me and my heritage, yet I reflected that I was part of the problem, too, as I didn’t know them and had all kinds of misconceptions. To be represented correctly, I would need to represent them correctly myself, and I knew, with shared values, we all had an obligation to work together to celebrate the greater sum of our different parts.

Rabbi Rosen worked with interdenominational religious bodies including the Reform Shul to set up a facility in the area to provide cheap meals for vagrants. To him this was an act of public relations as well as a moral obligation. These projects were not directly political but inevitably had political implications.

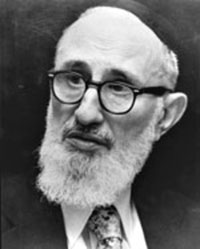

Rabbi David Rosen

Rabbi Rosen remembered the tension caused by his determination to speak challengingly though not irresponsibly, at the services for Republic Day for which the shul had prepared special programmes and issued invitations to City Councillors, Parliamentarians, Provincial Councillors and leaders of Jewish organisations in the city. The press reported him as maintaining that religious leaders, particularly Jewish religious leaders, who separated politics from religion failed in their duty. When the Board of Deputies and the SAZF honoured Prime Minister Vorster on his return from a visit to Israel in 1976, Rabbi Rosen refused to attend and said so from his pulpit. He condemned the demolition of squatter’s homes at an interdenominational service of compassion in the City Hall. Another time he was quoted as saying the only way to remain in this society as a Jew was to stand up for principle and for integrity and against injustice.

Rabbi Rosen started to get anonymous death threats and the security police started tapping his phone. Although some members of the shul disapproved of his stand, the great majority supported him as did the Cape Jewish Board of Deputies and Rabbi Duschinsky, head of the Beth Din.[ii]

His work permit was not renewed and he left South Africa early in 1980 [iii] being replaced by Rabbi Dr Elihu Jack Steinhorn from New York. who had been the rabbi at Temple Agudath Shalom, Stanford, Connecticut. He had trained under Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik, a major voice in Modern Orthodoxy, and held a PhD in philosophy from New York University.

Rabbi Steinhorn Rabbi Soloveitchik

[i] Kessler, Solly, “The rabbinate in the apartheid era”, Jewish Affairs, 1995, 50 (1) 31-35

[ii] From Cape Town, Rabbi Rosen became the Chief Rabbi of Ireland, “which is not a job you can do well if you’re not involved in interfaith relations “, he said. At present he serves as the International Director of Interreligious Affairs of the American Jewish Committee, the International President of the World Conference of Religion for Peace, the Honorary President of the International Council of Christians and Jews and an Executive member of the World Council of Religious Leaders.

[iii] He is also one of nine board members of the King Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue, with representatives from the Vatican, the Church of England, the orthodox church and Muslim scholars from Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Iran. Rabbi Rosen commented that “for a Saudi king to have endorsed an Israeli rabbi to be on this board is not insignificant”. He has also been honoured as a knight of the Order of St Gregory the Great by Pope Benedict XVI for his contribution to promoting Catholic-Jewish reconciliation and by Queen Elizabeth II with a CBE.