As told by their son, Jonathan Freedberg

From the crucible of war, my father returned to South Africa sometime in 1946, going to live in Oudtshoorn the hometown of my mother, Alma, where she had been staying with her father during Solly's absence. There were a number of Jewish doctors there at the time, all wondering what to do next, when my Dad received a summons from his mother, my grandmother Shalia, to come to Parow to open a practice. The temptation? A free house!

I have often wondered what brought so many other Jewish doctors to this outpost of Afrikanerdom, but never did ask anyone that particular question. Nonetheless, my father opened his practice, his surgery attached to our home. With the clinical experience wrought of the battlefield, the nature of general practice at the time, my father did it all; gyneacology, obstetrics, broken bones, you name it. He had many colleagues among the surgical fraternity and often assisted in the operating room, principally as the anaesthetist, as he had accumulated much experience 'up north' and through the European campaigns.

During the latter part of the War, my Dad was 'fortunate' to have visited Hitler's bunker as he followed the Allies through Africa, Italy, and into the rest of Europe. On one vacation trip, he was told to visit the Commanding Officer (CO) in the town to which he and his buddies were going (in a 'stolen' Jeep). The CO gave him an address and my dad and his buddies spent a comfortable night in the accommodation provided. Turned out it was a brothel! Ask no more!

It is an abiding memory for me to remember my dad gussied up in a formal suit, always with a carnation in his buttonhole, little (big?) black bag in his hand, brushing his hair in front of the full-length mirror guarding hairbrushes, car keys, sunglasses in a pottery bowl on a long wooden table beneath the mirror, setting out every morning to do his rounds before returning to his rooms later to see patients.

The telephone was the bane of our lives. In those days, one landline served all. During business hours, God forbid any of us were caught using the phone for anything other than the most immediate needs before being yelled at. The fact that my Dad absolutely detested using the phone was, as I realized in later life, simply the result of its continuing intrusion in his life.

I cannot remember him initiating any other than the most needed calls, he refused point blank ever to answer the phone and as I grew older, I had a really tough time convincing patients that I was his son, not him! I guess our voices were identical and you can imagine how much ill-will and suspicion was aroused at what his patients clearly thought was a subterfuge. His aversion to the phone lasted all his life, an irritation never to be yielded to, even to the extent of never calling us after we had emigrated unless he deemed too long a period had elapsed since my last call to him, which was thankfully not often. (It's ironic, that we who now live tethered to our smartphones are probably all suffering the same phobias).

Lunch was served promptly at 1pm every day. With the radio on, we listened to the news over lunch. If it was 'teatime', we listened to music. So, whereas my dad developed an aversion to the phone, I have successfully managed to maintain an aversion to any form of background music. The radio interfered with everything! To this day, you will find me insisting in restaurants that the 'muzak' be turned down….

My mother was always there, in the background it seemed, but really in control of events. Also a working doctor (at the local clinics – the two of them simply could not work together). The conversation around the table was always a discussion of their medical cases, absorbed as they were in their vocations.

Let me not leave the reader to think that was all that was discussed – on the contrary, discussions were wide and far-reaching, but the medical element remained a perennial, accentuated on those occasions when a gathering of (medical) friends was entertained at our home and then it seemed as if there was no case history in the Northern Suburbs that all these doctors were not involved in.

Memories surface as I write: The occasion, sometime after my dad's retirement from private practice, when he was at the theatre and bumped into an old (not in years) patient. When he replied to her greeting in some puzzlement, saying he did not remember her, her tart reply was: But Doctor, you delivered all of my five babies. 'How can you not remember me?', to which my dad replied: 'Well, I was clearly not looking at your face'!

Another time, my mom and I went to the surgery door at about 3 am one morning (I was the nominal security guard), to find an old man standing at the door, bent forward at the waist, his arm twisted behind his back, clearly in pain. To my mom's enquiry as to what ailed him, he said: 'Ag Dokter, ek kom met my rug' (Oh Doctor, I am here with my back – literal translation, but not quite what he meant), to which my mother disingenuously but somewhat annoyed by this untimely intrusion for a problem that did not merit being woken at this ungodly hour replied: 'Nou hoe kan jy sonder jou rug gekom?' – 'So, how could you possibly have come without your back?'

My father was a true fatalist; life was pre-ordained for him. At one point, he and my mom decided to make Aliyah and he had arranged to sell his share of the partnership practice that he enjoyed with Leonard Mendelsohn. The sale fell through at the last minute and so my father cancelled all further plans to leave for the Promised Land. Who knows what our history would have been had we gone? Now, my daughter lives in Tel Aviv, my sister's children live in Israel and it seems that most of the family ended up there despite my dad's fatalism. Me? After a 6 week visit to Israel as part of a Herzlia contingent, I simply could not imagine myself living in that Middle Eastern mentality.

So, the years passed. Eventually, tiring of the constant interruptions during the night, the 'traipsing' through Elsies River, my mom insisted that he sell the practice. He did, and I believe, my father's own reports elsewhere recorded in this saga, reflect a good part of the rest of his history.

As late as his latter years, some patients still visited him in his apartment in Sea Point, unwilling to acknowledge his retirement, my father happy to 'keep his hand in'. The arrival of the 'New South Africa', found my dad working at a hospital in Woodstock. He was now 93, ever refusing

to give up his life's work. Someone in the Human Resources department called him one day asking him whether the date of his birth in the file, 1915, was a typo. Should it have been 1951? I will not describe his indignation at such an affront, but the upshot of the call was that a couple of weeks later, he was urged to resign 'to give the new doctors a chance'.

Much disgruntled, he realized his time was up and resigned indignantly. It was only when he was 96 that he finally admitted to me that it was probably time for him to have stopped working. Quite an admission from an old trooper.

Nonetheless, on his monthly visits to the hospital to pick up his medications (two quadruple bypasses and advancing age to be taken care of), the Matron of the hospital (what a quaint term in this American environment), used to keep a collection of his 'old' patients for him to attend to ex officio. He used to spend the morning exercising his prodigious skills, enjoying the continuing service he provided.

Another story comes to mind: When visiting Cape Town one year after my emigration to the States, we ended up discussing some family history. My maternal grandmother had died of diabetes two weeks before my parents were married in Oudtshoorn . The question of patient death became the focus of the conversation. My father told me of an experience he had with a patient who was seemingly, beyond a cure. Advising him to put his affairs in order as there were no further medical solutions to his ailments, my father was confounded (and delighted) when, sometime later the same patient appeared on his doorstep, having fully recovered. There was no explanation, but my father told me that the lesson for him was that doctors were not God. It was the last time he told any patient that Death was coming to make a call….

Ahh, my dad was kind, charming, good looking and so loved by his patients. No, not loved, adored! He had a wonderful empathy for the sick souls that beat a path to his door. Yet, as a father, he was mostly emotionally removed, critical without the balance of encouragement, demanding.

All his life, my dad had told me that as long as his mind functioned, he would want to keep living, irrespective of his physical condition. Some months before he died, we were eating breakfast together when, popping all his daily medications into his mouth, he bemoaned the fact that his 'body was falling apart'. When I retorted that at his age, it was to be expected and that he had been granted his life's wish of eternal cognitive lucidity, he looked at me for a moment and then burst out laughing. Some moments are truly precious.

At the end, deterioration and imminent death was inevitable. Dragooned into dialysis, he rebelled after the third session and said he had had enough. When confronted by the physician who asked him if he knew what he was saying, in true 'Solly' fashion, he acerbically told the doctor to get lost! He went home, and a day or two later, after sitting and watching the sea, he told Hannah he was tired and was going to rest. He died in his sleep a couple of hours later. What better way to go?

I have said little of my mom, for no reason other than the focus of this epic seems to have been elsewhere. Nonetheless, my mom worked all her life until they moved from Parow at the local clinics, three times a week, so as to be around for us kids. Sometimes fetching me from school (Herzlia), and being an attentive and loving mother, is how I remember her in some ways. Being unable to cook, she initially thought that to make mashed potatoes one first had to mash them before cooking. Her exploits in the kitchen are not part of her history, other than the butter cakes she always made for us. Thank heavens for Rita, our maid. (My gosh, what privileged lives we led).

We are mostly the products of our upbringing. Responding to little encouragement, made me determined always 'to do better'. Maybe that helped me to be successful in later life, in emigrating. My mother bestowed an endless capacity for compassion in me, a need to help, and so we live on. May we live on for yet a while.

Solly Freedberg’s reminiscences

After being demobilized out of the army in 1946, I decided to start my life as a GP in Parow much to the disgust of the doctors already well ensconced during the balmy days of the war where most of them accumulated fortunes. I was loaned 1200 pounds from the government to start my practice. It was a huge amount to keep me going but after 5 years had to take in two new doctors to ease my life.

During those 5 years it was night and day slogging it out whatever the weather. This kind of life meant that I had very little time for family. Parow was a real 'dorp' during the 1940s. There were no roads or electricity so that a call after dark meant a real hardship especially in the Coloured areas and sometimes one took one’s life in one’s hands especially when the husband had had too much to drink and could cause problems.

However, one of the women who handled the midwifery in these poor areas took me under her wing and I knew if she called for help I was going to have a hard time delivering the babies.

This lady had no official training as a midwife but instinct made her aware of impending trouble. Calls were 5 shillings in the surgery and 7,6 shillings for a call to the home. Very seldom could I get 15 shillings for a confinement but I realized that in those days money was of real value. One wintry night, raining cats and dogs, I was called out to a troubled confinement in the worst part of Tygervalley and had to walk about a mile in the rain to get to the house led by the husband.

The woman had an obstructed labour, but after much praying and sweat and tears a healthy baby was delivered. The family was so pleased the husband offered me 3 pounds which I took with much alacrity.

On returning to my car I found to my disgust that it was stuck in mud. The husband, still in a euphoric mood, said he would get his donkey cart to pull me out of the mud. One hour later I was freed and thanked the husband, then started to pull away when he stopped me. He then proceeded to demand 5 pounds from me for his efforts to free my car, so I lost on that deal!

The years, 1950 / 1960 / 1970: The fruitful days, tinged with tragedy

After the children left home, I decided to enter the Civic side of life. I had numerous requests to stand as a councillor for the local municipality, but wary of politics, at first I refused. The antisemitism and the hatred of anything not Nationalist eventually persuaded me to stand. My opponent was a rabid, extreme antisemite, a dentist by the name of Dr Van Nierop. He was already a member of parliament.

On the day of the election, he castigated and warned me, that if he lost the election, my life would not be worth living. I lost by 6 votes, but Van Nierop lost a great deal of face, as he almost lost the election. Six months later, l was successful and remained on the council for at least 15 years.

Corruption was rife, but they had a strong adversary in me. They eventually consoled themselves and voted me in as Deputy Mayor. But their prejudice prevented them from giving me the doubtful honour of being Mayor of Parow.

Over time I developed and expanded a branch council of the medical profession of the Northern Areas and was rewarded by becoming President of the branch for a few years.

This effort of keeping the doctors together on a professional basis, really paid off because I became the first Jew to be appointed to the permanent staff of the new Tygerberg Hospital in 1974.

The post was to organize and run the whole new outpatient's department which had not been provided for in the original scheme of staff. Only then did the authorities and medical staff come to realize what a Jew was really worth. As a result of the growth of the department, I persuaded the authorities to give me help. I appointed my wife, who was a doctor, to assist me in handling all the patients.

A year later tragedy struck, and my wife died of a massive heart attack, aged 59 years.

In my last year of private practice, my wife and I both realized that for 30 years, we had not enjoyed one undisturbed night. I took that to be a sign to leave private practice.

The outpatient's department had now become so busy, that more doctors were needed. I managed to appoint Angel Mallach, Herschel Peires, Gerald Anstey, and two other non-Jewish doctors to assist in the load.

For the next 10 years I gave of my best, including running a stroke rehabilitation hospital in Goodwood. Because of my intense involvement in the various institutions, the committee, of which most of the members were heads of departments and staunch Nationalist party supporters, I was elected as President of the Boland Tygerberg branch of the Medical Association, for which I received a medal.

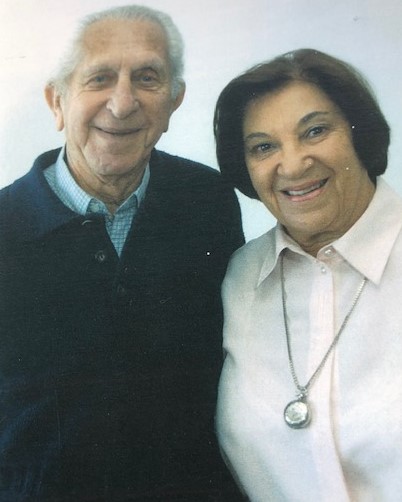

In 1979, I remarried Hannah Dembovsky, a widow from the Southern Suburbs and have been happily married for the last thirty two years.

My late wife and myself took yearly holidays overseas and in 1960, we visited Israel. During the WWII every time I had a few days leave, I would visit Palestine for a break. At that time, Tel Aviv was only the Beach Road and the Dan Hotel was in the process of being built. I usually stayed at a B&B run by a German refugee.

I knew that Simie Weinstein was with the Zionist Federation, working with Sam Levine, who was in charge. Weinstein was an old Oudtshoorn guy and since my late wife had come from Oudtshoorn , we made contact with him. We set up an interview with Sam Levine.

At the meeting he was most helpful and suggested that I emigrate to Israel as soon as possible, as at that time, I would be the only English-speaking GP in Tel Aviv. On returning to SA, we made all the necessary arrangements to emigrate. As it involved many aspects, I soon found a buyer and thought we were to be on our way. When the time came to being paid, I opened the newspaper one morning, only to find that the buyer had been declared insolvent! I took this as an omen and to my regret, I remained in SA.