With the increasing numbers of members, marriages and children, the synagogue now lacked the necessary facilities to provide for them and embarked on a project that would provide an overflow for services, a function hall, a Talmud Torah, a preparatory school, a kindergarten, and would house the Chevra Lomdei Torah, the youth section, the Ladies Guild and the Work Party. On 25th May 1952 the foundation stone of the Synagogue Centre was laid by Cecil Hyman, the Minister for Israel and that of the Talmud Torah was laid by Archie Sacks,[i] the chairman of the Building Committee, who had played a leading role in the construction[ii]. Rabbi Rosen called him a remarkable man, not only for his unflagging dedication as a communal worker all his life but also for his clear and agile mind.[iii]

In honour of Chaim Azriel Weizmann, the first President of Israel, the building was named the Weizmann Hall. Weizmann was to pass away six months later.

Weizmann Shul: For the High Holy Days, the Weizmann Hall was converted into a shul in which more than a thousand people worshipped. The seating committee would battle to allocate seats. Some complaints were justified such as an objection by Mr A. Krupp whose wife was ejected from her seat at a batmitzvah by the seat holder - so the policy was made that reserved seats were for high festivals only (11.10.1954).

Weizmann School: The school buildings had a recreation hall with shower baths and cubicles, a stage and kitchenette. When it started in 1953 it took children from the age of five giving them a secular school syllabus plus Hebrew with the hope that it would develop into a full day school up to Standard 2 and eventually to Std 5. The afternoon Talmud Torah had enrolled over 70 children with over 50 in the beginners’ class.[iv] The numbers increased so rapidly that first an additional block of ten classrooms had to be added to the Weizmann School six years later but that too became inadequate for the community’s burgeoning needs. Communal leader Gerald Kleinman[v] was to point out that the leaders of the G&SPHC and the planners of the Weizmann Hall Complex could not have envisaged that the premises planned for a Talmud Torah would, in barely more than two decades, house some 400 pupils of a Hebrew day school. Although their understanding of congregational responsibility for Jewish education was seen by incorporating plans for a Nursery school, divisions in the congregation leadership resulted in costly delays in a time of spiralling costs. Still planning ahead, when Chatsworth Flats in Regent Road. adjoining the Weizmann Hall came on the market the Shul bought this for future congregational requirements. Its rent-controlled flats proved to be a huge financial drain on the congregation with a low income and high expenses and the financial situation became so bad that they had to sell it. [vi]

Weizmann Nursery School: In 1962 they bought the Knightswood Hotel which adjoined the School in Clarens Road to become a nursery school which filled such a need that in 1967 120 children attended of whom 72 were children of members and it had already received 49 applications for the 40 1968 vacancies (5.9.1967). Later the nursery school would become classrooms for Weizmann School and would receive its own premises when the Max and Rose Leiserowitz Nursery School was completed in 1976 with a full capacity enrolment. Weizmann School merged with the United Hebrew Schools.[vii] Archie Sacks had been instrumental in persuading the Leiserowitzes that, as they were childless, would they not like to leave some money to benefit children.[viii]

Weizmann Hall: The Weizmann Hall was the biggest Jewish communal hall in the Cape, could seat 1,300 people, had a large stage and a well-equipped kitchen and was used as well for communal and private functions, weddings and celebrations, both for the congregation and for the larger Cape Town public. Jazz musicians were hosted there in the 1950s and 1960s [ix] Even the Union Law Society held its conference there in 1962.

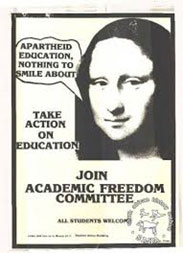

From the committee’s decisions when it came to letting the hall to outside bodies, one can gauge its disapproval of apartheid together with a strong measure of caution. The hall could not be used for meetings or gatherings of a political nature. The G&SPHC committee was ambivalent about a concert in 1958 to raise money for the dependants of the Treason Trial accused. This trial of 156 people lasted from 1956 to 1961 when all the defendants, who included Nelson Mandela and fifteen Jews, were found not guilty. While they had sympathy for the accused and their families, they were scared of political repercussions from the hostile and repressive state. They agreed on conditions that the organisation hiring the hall was a registered welfare fund that aided members of the families of the accused persons in the Treason Trial; no advertising or tickets should give the impression that the organisation responsible for the concert was of a political nature, and no speeches or addresses could be made on the night of the concert. The organisers agreed and the concert went ahead (21.7.1958). Similarly, when the Academic Freedom Committee booked the Major Weizmann Hall for a symposium in 1971, they agreed to waive charges, but, once again, first required a reassurance that to do so would be “entirely lawful and not in any contravention of any laws” (15.4.1971). Again, this shows the constraints they were operating under by living in what had become to all extents an oppressive police state with laws even regulating what could be said.

When the National Party wanted to hire the hall, however, they turned it down, saying that no public political meetings could take place there (13.2.1962). They could not use that excuse when the Jewish Board of Deputies asked to use it for a lecture by visiting Rabbi Freehof, president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis and the World Union for Progressive Judaism. It required the reassurance of Board chairman Sydney Walt that there would be no Reform propaganda in Rabbi Freehof’s lecture before the shul committee magnanimously said that at no time was there any question of not letting the hall to a Reform Rabbi (29.1.1962).

Finally, economic considerations became important and the committee decided to let the hall for political meetings and to inform political parties of their decision. The executive reserved the right to use their discretion in the case of undesirable meetings but were sufficiently cautious to take out an insurance policy against riots in case meetings became rowdy (3.1.1964). This created additional worries and they considered only using it for communal functions and stopping to let the hall out for functions (3.3.1964) such as Bop-hops, which would not be allowed on Thursday or Saturday nights (2.6.1964). Another problem came from police visits answering neighbours’ complaints that the noise of the bands was disturbing the peace (25.2.1969).

Next to be considered was whether the Weizmann Hall could be hired to "Non-Europeans”. In 1958 the committee found that they could not do so as they lacked separate sanitary functions as required by the law (25.2.1958). This must have been sorted out because despite the Group Areas Act and the Separate Amenities Act, the hall was licensed for public entertainment, the right of admission was reserved, and the committee decided it would be very difficult to exclude them. Anyway Mr Reuben, the Weizmann Hall manager, assured them that Non-Europeans were better behaved and more co-operative than European audiences.

[ii] Educational, ecclesiastical, charitable and Zionist causes were all dear to him and he served on the committees of Herzlia, UCF IUA, SAZF, Oranjia and Highlands House. Archie and his brother–in-law Joe Heneck were keen collectors for the synagogue and for other community causes, obituary, G&SPHC Rosh Hashanah Annual, 1979 – 5740

[iii] Rosen, Rabbi David, “Rabbi Rosen Remembers”, G&SPHC Rosh Hashana Annual Golden Jubilee, 1983 - 5744, 57

[iv] SA Jewish Chronicle, 13.2.1953

[v] Kleinman, Gerald, “Proud Record of Achievement”, G&SPHC Rosh Hashana Annual, 40th Anniversary, 1974 – 5735, 16

[vi] Smith. Norman, Messages from Past Presidents. G&SPHC Rosh Hashana Annual, 70th Anniversary, 5765, 10

[vii] G&SPHC 43rd annual report, 1976 - 5736, 8-9

[viii] Interview with his daughter, Rene Kleinman, 8.1.2018

[ix] The writer remembered going as a schoolgirl to a concert by Tommy Steele - Britain's first teen idol and rock and roll star in March 1958. Her friend’s brother in-law, the house master of the Herzlia boarding school, had given them complimentary tickets. The two girls arrived to see a huge crowd of screaming teenagers outside the Weizmann Hall and decided to join them to watch the singing sensation arrive. When they got bored and went inside, they discovered that they had missed half the show as Tommy Steele had entered through the back.