With the appointment of Rabbi Shrock tension between the two large synagogues developed. The Gardens Synagogue was the oldest synagogue and their rabbis considered themselves to be the leaders of the Jewish community. The G&SPHC, although initially intending to become a branch of the Gardens Synagogue, had opted for independence, and, as previously mentioned, Rabbi Shrock was to write “What a different tale there might have been to tell if the leaders of the Gardens had been more amenable to reason! But then, how were they to know that within twenty years or so, the Sea Point congregation would become the largest in the Cape?” He could not resist another dig at the Gardens Shul.

Furthermore, neither rabbi was prepared to be considered subservient to the other, one serving the oldest, the other the largest congregation and both guarding their self-importance. This could be seen both in Rabbi Abrahams demand that he be the only one to officiate at Rabbi Shrock’s induction, and in Rabbi Shrock’s sensitivity when he was excluded from invitations to participate in communal events.

In 1947 the committee complained to the Board of Deputies that Rabbi Shrock had been overlooked and not given the necessary honours by it and by the Dorshei Zion Association. In 1949 the committee met with the Board to complain that Rabbi Shrock’s name had been omitted as a patron of its United Appeal Campaign (25.7.1949). (He was then appointed a campaign vice-chairman.) It is difficult at this stage to ascertain if the sensitivity to rejection came from the rabbi or the committee – probably both, particularly seeing the committee’s touchiness when it came to Mr Sive’s claims.

Rene Kleinman recalled in 2018 that Rabbi Shrock was a very nice rabbi, respected and liked by all, whereas Rabbi Abrahams had a big ego and did not get on with many people and was never considered to be the Chief Rabbi by the G&SPHC which prided itself on being a centrist synagogue[i].

Then Rabbi Abrahams gave instructions that Rabbi Shrock, who had been appointed by the United Council of Synagogues, was not to be called to the Beth Din (13.9.1949). This insult was a casus belli. Justice Joseph Herbstein was appointed to bring about peace. He presented a memorandum at a special meeting that he chaired with delegates from the Gardens Shul and the G&SPHC to restore unity. G&SPHC’s Abrahams and Mauerberger refused to meet unless Gardens Shul extended some gesture of goodwill to their congregation, and the only basis under which they would negotiate would be if Rabbi Shrock was recalled to take his place on the Beth Din.

Relations remained frozen with much personal animosity between the rabbis and the congregations but the Marais Road shul did agree to accept an invitation some months later to attend a Chanukah Service at the Gardens Shul on 18th December where a memorial plaque was unveiled to those members of the Gardens Shul who had made the supreme sacrifice as well as those who had served in the armed forces during the Second World War.

That temporary truce did not last, because ten days later they wrote to Justice Herbstein saying that the position had been aggravated more than ever because in the meantime the Ministers Association had met, and passed a resolution to urge the United Council of Synagogues (UC) to accept Rabbi Abrahams as the Chief Rabbi of Cape Town. This was ironic as Rabbi Abrahams’ predecessor at the Gardens Synagogue had voiced strong objections to a chief rabbi being appointed when Rabbi Landau became Chief Rabbi in 1915. Rev Bender had written at that time that a Chief Rabbi to him was a “superfluous and dangerous anomaly” – but then complaints always come from the loser, not from the winner.[ii] Similarly in no way was Rabbi Shrock or the G&SPHC prepared to be under the control of Rabbi Abrahams and the Gardens Synagogue.

The committee decided to bring their dispute with the rabbonim to their whole congregation explaining that they strongly deprecated the expulsion of Rabbi Shrock from the Beth Din, that they urged the immediate recall of Rabbi Shrock to the Beth Din, failing which the congregation was going to resign from the UC and explore the possibility of joining the United Council of Orthodox Congregations of South Africa instead.

The Board of Deputies was called in and invited the executive to meet with them on 25.1.1950 to settle the dispute and the Board undertook to take immediate action to recall Rabbi Shrock to the Beth Din. The Beth Din sent a letter extending an unconditional invitation to Rabbi Shrock to resume his position on the Beth Din. The G&SPHC replied politely expressing their appreciation on their prompt action taken to settle the unfortunate dispute.

Peace did not reign for long, because on 16.2.1950 the committee reported that they had been invited to a meeting to appoint a Chief Rabbi and a Deputy Chief Rabbi. They decided to attend and ask for a postponement. The meeting was packed, and the G&SPHC representatives decided to leave before the vote together with the representatives of the Roeland Street Synagogue and half of the representatives of the Vredehoek Synagogue. The implications of the appointment were that the chief rabbi would be able to control and interfere in the actions of other synagogues and their rabbis would all be subservient to the Chief Rabbi who would be presumed to be the most knowledgeable and the most qualified to determine halachah. The post of Chief Rabbi was a British convention and had not existed in Eastern Europe where each rabbi was responsible to his own congregation. Lithuanian synagogues did not have a formal system of membership and formal affiliation to congregations were not part of their tradition.[iii]

Despite their absence, the meeting agreed to appoint Rabbi Abrahams as Chief Rabbi and Rabbi Shrock as Deputy Chief Rabbi. The G&SPHC decided that they would definitely not accept the principle of a Chief Rabbi and that they would federate with the Roeland Street and Vredehoek synagogues to strengthen their position. They agreed to withdraw from the Cape Committee of the Board of Deputies and from the United Council of Synagogues and hold a meeting with Roeland Street and Vredehoek synagogues.

Chief Rabbi Abrahams

A letter was sent on 31st March to the Board of Deputies stating that the G&SPHC had unanimously resolved to withdraw its association from it.

A letter was also sent to the Chairman of the UC stating that the G&SPHC had unanimously resolved to withdraw from it forthwith.

The Board responded that it had unanimously agreed not to accept the resignation of the G&SPHC and earnestly requested that it reconsidered its decision. The G&SPHC committee replied that after careful consideration it regretted that it was unable to depart from its previous decision. A special meeting was called for 11th April.

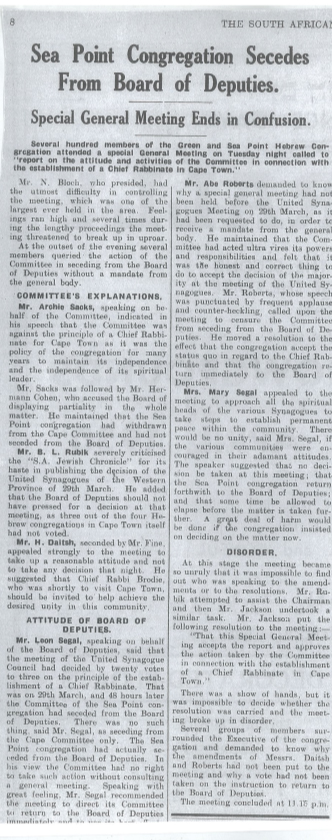

What happened next was picked up from an article in the South African Jewish Chronicle datelined 12th April 1950.

SEA POINT CONGREGATION SECEDES FROM BOARD OF DEPUTIES

SPECIAL GENERAL MEETING ENDS IN CONFUSION

The journalist wrote that the meeting was called to report on the attitude and activities of the committee in connection with the establishment of the Chief Rabbinate in Cape Town. Mr N Bloch who presided had the utmost difficulty controlling the meeting which was one of the largest ever held in the area, feelings ran high and several times during the lengthy proceedings the meeting threatened to break up in uproar. Several members queried the action of the committee in seceding from the Board of Deputies without a mandate from the general body. Archie Sacks speaking on behalf of the committee indicated that it opposed the principle of a Chief Rabbinate for Cape Town as for many years it was the policy of the congregation to maintain its independence and that of its spiritual leader. Hermann Cohen accused the Board of Deputies of displaying partiality. The Sea Point Congregation had withdrawn from the Cape Council of the Board, not from the National Board. BL Rubik criticised the SA Jewish Chronicle for its haste in publishing the decision of the United Synagogues of the Western Provinces. The Board of Deputies should not have pressed for a decision as three quarters of the Hebrew Congregations in Cape Town had not voted.

Leon Segal, speaking on behalf of the Board of Deputies said with great feeling that the meeting of the UC had decided by 20 votes to three on the principle of the establishment of a Chief Rabbinate on 29th March and 48 hours later the G&SPHC had seceded from the Board. There was no such thing as seceding from the Board. The committee had no right to take such action without consulting a general meeting and he recommended that the meeting direct the committee to return to the Board immediately.

AM Jackson responded that he had always been against the creation of a Chief Rabbinate, and it was in the interest of the congregation to maintain strict independence. It was also vital to maintain the freedom and independence of the incumbent of the pulpit. The meeting became so unruly that it was impossible to find out who was speaking to the amendments.

The article continued that Jackson had put the following resolution that the Special General Meeting accepted the report and approved the action taken by the committee. (Jackson was in an invidious position because, although he had been involved in the G&SPHC since its inception he had also been Board chairman until the previous year). There was a show of hands but it was impossible to decide whether the resolution was carried and the meeting broke up in disorder.

After a discussion, Jackson moved the full resolution which was carried that the meeting instructed the committee to withdraw its resignation from the Board of Deputies (Cape Committee) but confirmed the action of the committee on the question of establishment of a Chief Rabbi in Cape Town and in resigning from the UCHC.

The Chronicle also contained a bordered block:

|

Rabbi Shrock regarded himself as the equal of Rabbi Abrahams. No way would he find himself in a position where he would be taking instructions from Rabbi Abrahams, now a Chief Rabbi Abrahams.

Two days later the Chronicle contained angry letters. One, from DISGUSTED said his experience at the meeting would certainly not induce him nor any other member of his generation to be part of the congregation. Pandemonium seemed to have been the order of the night. A complete lack of appreciation of the ordinary rules of debate and good conduct prevailed. Although he was prepared to support the committee’s conduct, he was bound to be an honest witness to the events of the evening to testify that the overwhelming opinion of those present were against its actions. In the hurly-burly and excitement created, it came as a shock to him to discover that it had been ruled that the majority had voted in favour of the committee’s actions, he could not accept that ruling as a true reflection of the will of the congregation and it would have been desirable for a ballot to have been held or a proper count taken.

Rubik also sent in a letter sympathising with the chairman who had a most difficult task but expressing his deep regret at the high-handed action taken by the executive. He had moved an amendment that Chief Rabbi Brodie, due to visit Cape Town from London, be asked to arrive at an honourable and peaceful settlement. However, his amendment was not even put to the meeting.

Five years later and the dispute had still not been resolved. Rabbi Shrock had been approached over the past few months to accept the proposal to join the UC but he would only do so on the proviso that the Chief Rabbi would have no jurisdiction over him or his congregation which had gone from strength to strength and had its own spiritual head and did not need a chief rabbi. The three dissident congregations had drawn up a five-point memorandum for consideration by the UC in order for them to re-join it. These included that the chief rabbi could be re-elected for a further ten years after which he might be eligible to serve a further ten years, that he would have no jurisdiction over affiliated synagogues or their rabbis, and that an advisory board consisting of laymen and rabbis would consult with the chief rabbi in communal matters. However, it had first been shown to Rabbi Shrock who was adamant. As far as he was concerned, even if the congregations joined the UC neither he nor his congregation would recognise Rabbi Abrahams as Chief Rabbi or his jurisdiction over them.

Although the UC would not accept the memorandum, its chairman suggested that representatives of the three dissenting congregations interviewed Rabbi Abrahams, and if he accepted the proposal, the UC would follow suit.

Although Rabbi Shrock regarded the interview as uncalled for, it went ahead and they presented their proposals with an amendment by J Walt to include that, after a year, the Chief Rabbi’s position should be reviewed by the UC with a view to extending his position until the age of 65. Rabbi Abrahams asked to view the memorandum in writing and responded that if the matter went forward for review after a year, he would expect to be appointed chief rabbi for life.

Rabbi Shrock had accepted his position in Sea Point on the understanding that it was an independent congregation. He claimed that he was quite prepared for Rabbi Abrahams to be chief rabbi of UC and for the G&SPHC to join the UC but he would not tolerate Rabbi Abrahams having jurisdiction over Sea Point while Rabbi Shrock was its spiritual head. If he had to work under Rabbi Abrahams, his position would be untenable and if he decided to relinquish his position for that reason, he assumed that he would be adequately compensated!

The result could have been predicted. A special meeting was held (7.3.1955) to agree on the terms under which the three congregations would re-join the UC. These included that each affiliated synagogue would be deemed to be completely autonomous and independent and the rabbi of each synagogue would be the spiritual head and leader of the congregation to which he held office under the sole jurisdiction of the executive of his congregation, and that by joining the UC it did not imply that the congregation would be under the authority of the Chief Rabbi. Rabbi Shrock started to look for another position and left the following year for Durban where his honour was satisfied - he became Chief Rabbi of the Durban Hebrew Congregation and Rabbi of the Communities of Natal (1956-65). The congregation gave him a farewell reception but he refused to accept his farewell gift of a canteen of cutlery.

The G&SPHC soon discovered that Rabbi Shrock had been right and its independence had certainly been curtailed. Only the UC executive could decide which rabbis could join the Beth Din. All synagogues had to accept the UC constitution without reserve. All communal services would be arranged only by the UC. All special prayers would be issued only by the Chief Rabbi. All the sermons at all radio broadcasts, communal services and functions arranged by the Beth Din and the UC would be delivered by the Chief Rabbi in his capacity as spiritual head. If the Chief Rabbi decided to allow another rabbi to do so he insisted on vetting and editing their sermon beforehand (17.4.1957).

Chief Rabbi Abrahams

Thus ended an era of independence. But Rabbi Shrock was no longer around to object. Peace finally came in 1969 when it was agreed that there would only be one chief rabbi in South Africa to be based in Johannesburg – Rabbi Casper (28.8.1969).